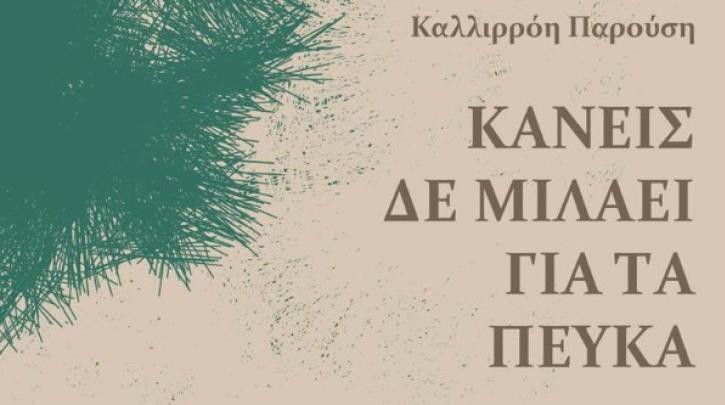

Kallirroi Parousi was born in Ermoupoli, Syros, in 1988. She studied law, European civilization and literature in Athens, Thessaloniki and Paris. She lives and works in Athens. Her first book, a short story collection titled Κανείς δε μιλάει για τα πεύκα [Nobody talks about pines] (Kedros Publishers) received the ‘Anagnostis’ Award for Best Newcomer Prose Writer in 2017.

Kallirroi Parousi spoke to Reading Greece* about the book, explaining that ‘pines’, which appear in all the short stories, symbolize “the promise of hope and at the same time its defeat”, adding that she “compiled and appropriated all those trivial and often seemingly insignificant incidents of the everyday life” in order to “literary capture the image of a society of puppets: a contemporary swamp that swallows everything”.

She also comments on the argument that Greek writers have a preference for short form noting that in Greece there is “a longstanding and rich tradition not only in short stories and poetry but novels as well” and that there are “exceptional novels” by young Greek writers. She explains that she is interested in “a literature that seeks to be a worthy opponent to the dominant discourse” and concludes that the role of a writer is often to hint at “the subversion of well-established conventions” and to “urge towards more groundbreaking approaches vis-à-vis conception, interpretation and reading”.

Your first book, a short story collection titled Κανείς δε μιλάει για τα πεύκα [Nobody talks about pines] received the “Anagnostis” Award for Best Newcomer Writer in 2017. What do pines, which appear in all of the short stories, symbolize?

The characters of the book, despite their distinct voices, all realize, justify and reproduce the conditions of slavery and collapse they experience being self-confined in an unbearable routine. They see their fantasies being shrunk; and the only thing that still connects and brings them back to reality is the evergreen pines, which symbolize the promise of hope and at the same time its defeat, since nobody talks about pines.

The ‘Anagnostis’ award for best newcomer prose writer is indeed a great encouragement to immerse myself deeper into prose and experiment with longer narrative forms, such as the novel that I’m currently writing.

To use Kostas Papageorgiou’s words, “her world is so real, almost televised or downloaded from the internet, yet so dreamy, that you get the impression that everything can be subverted, crashing against the wall of reality”. Which are the main issues your book touches upon?

Mr. Papageorgiou’s review of the book was quite insightful given that in Pines I used a somewhat risky coupling between the seemingly contradictory elements of the Internet language and the literary language, especially in the last short stories.

It was through this blending and experimentation that I tried to literally capture the image of a society of puppets: a contemporary swamp that swallows everything, an amalgam of voices and influences. Charming though it may sound as a narrative attempt, the unconditional inclusion in such a society may lead to self-destruction, as is the case with many of the characters.

In my first book, I opted for things I am really interested in narrating; I compiled and appropriated all those trivial and often seemingly insignificant incidents of the everyday life (for instance, a worker’s daily commute) which are worth paying attention to since they seem to have an impact on the mentality of the characters and appeal to those readers who have the ability to identify with them.

In his review of the book, Giorgos Perantonakis emphasizes on your long sentences, the alternations within the same sentences, the lengthy paragraphs, which are indicative of a language that does not fit in old molds. What purpose does language serve in your writings?

The contradictory forms and the inconsistencies of the characters constitute a way to portray cracks in their personalities. Through long sentences, alluded connotations and a selective linguistic experimentation (abrupt changes of place, time, perception and focus in narration), I tried to underline the fluidity of the characters, their volatile personalities due to the multiple stimuli they unquestioningly receive on a daily basis. Meanwhile, repetitions were often used as the binding thread between the short stories, attempting to emphasize on the underlying consistencies that exist among the heroes.

It has been argued that Greek writers have a preference for short form and that short story collections have outweighed novels and longer narratives. How would you comment on this?

I believe that the debate on the lack of good Greek novels is far from constructive and shouldn’t be further nurtured. There are exceptional novels by young, both newcomers and not, novelists who excel at long forms. Cases in point are Maria Xilouri, Lefteris Kalospyros, Nikos Chrysos, Kallia Papadaki, Angela Dimitrakaki and so many others. In this context, I was astonished to read in Karen Van Dyck’s bilingual anthology on modern Greek poetry that “the Greek novel barely exists”. I find the assertive character of this phrase a bit problematic. And this is not only because there are indeed, as I already mentioned, exceptional novels by Greek writers, but also because in Greece there is a long standing and rich tradition not only in short stories and poetry but in novels as well.

There is no reason to draw here a list of all the emblematic Greek novels written in the 19th and 20th century, such as Πάπισσα Ιωάννα [Pope Joan] by Emmanuel Roidis, Η Ζωή εν Τάφω [Life in the Tomb] by Stratis Myrivilis or Μενεξεδένια Πολιτεία [Τhe Purple City] by Angelos Terzakis. Suffice it to say that we should not just focus on the works of our major poets awarded the Nobel Prize or to the much praised modern Greek poetic production. Let us also give space and voice to all those writers who opt for longer forms such as novellas and novels.

Which are the main challenges new writers face nowadays in order to have their work published? What role do the social media play in the promotion of new literary voices?

The internet offers an astonishing, almost magical, opportunity to access foreign literature, as well as texts and approaches that broaden the canon of domestic tradition. And in many cases it has been noted that foreign influences prevail over domestic ones. At the same time, at the touch of a button, writers may have their work known and accessible to a wider audience. Amid this tremendous variety of voices, it has become difficult to discern the one that really interests you and which has the potential to spread and be heard as a beautiful song played by a street artist. That’s why a publisher’s work has become increasingly demanding. Following publication of a book in print, the social media more or less play their own role in its promotion. Personally speaking, I am quite indifferent to literature as a social sports and book review as mere book advertising on the Internet, so I try to manage social networks with prudence and caution.

“I believe that the subversive function of literature lies in the attempt to bestow stereotypical concepts with new meanings”. Could literature offer new ways to imagine what can be radically different realities?

I’m interested in a literature that seeks to be a worthy opponent to the dominant discourse, namely a literature that dares, a literature that experiments and counters itself not only in terms of content but also in terms of form and narrative techniques.

I think it was Jan Fabre in Journal de Nuit who wrote that a theater set is the hidden actor which implies a certain mental state. I have the impression that this is often the role of a writer who, through writing, hints at the subversion of well-established conventions and urges towards more groundbreaking approaches vis-à-vis conception, interpretation and reading. The magic of a worth reading literary work, which moves between tradition while trying to stride over and get past tradition, lies exactly in that it tries to elicit our attention and even exacts our involvement in the creative act of reading.

I believe that through reading good literature, we may stay vigilant, striving with life! Yet, caution is required. Literature constitutes the catalyst, which may cause fermentation, yet real change is not just a question of reading, and certainly not a question of reading only literature.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE

![Literary Magazine of the Month: [FRMK] and its Ten-Year Anniversary Issue ‘Tenderness-Care-Solidarity’](https://www.greeknewsagenda.gr/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2024/04/frmkINTRO2-1-150x150.jpg)