Pavlina Marvin was born in Athens in 1987, but grew up in Ermoupolis of Syros. She studied history at the University of Athens. She was a co-publisher and co-editor of Teflon poetry magazine (2008-2011). She also studied poetry in biennial workshop of the Foundation “Takis Sinopoulos”, and since then has not stopped ever. Her first book Histories from all around my world was published by Kichli Publishing (2017). Part of her work has been translated in English, French, German and Croatian.

Pavlina Marvin spoke to Reading Greece* about her first writing venture, Histories from all around my world, “a book about the art of saying goodbye to time, to bodies, to the real, to ourselves”, “a book that wonders bout the usefulness of the absurd”. Asked about “Teflon”, a poetry magazine she co-published, she explains that “it dealt unprecedentedly with issues that seems to have been up to that time of no interest to the literary community in Greece”, while “it re-approached issues from the viewpoint of a new generation which carried its own expressive particularities, reversals and concerns”.

As for the National Book Center of Greece, her doctoral thesis focuses upon, she comments that “EKEBI dealt with numerous important issues, most of which remain widely unknown”, adding that in her opinion, “there has been no national policy for the book, in the sense of setting mid- and long-tern strategic goals and developing relevant investments”. She concludes that “in every age there are remarkable poems and noteworthy poetic actions”, and that poetic creating is “a thread that links both the perceptible and the imperceptible, the real and unreal levels of this wonder that we call ‘life’”.

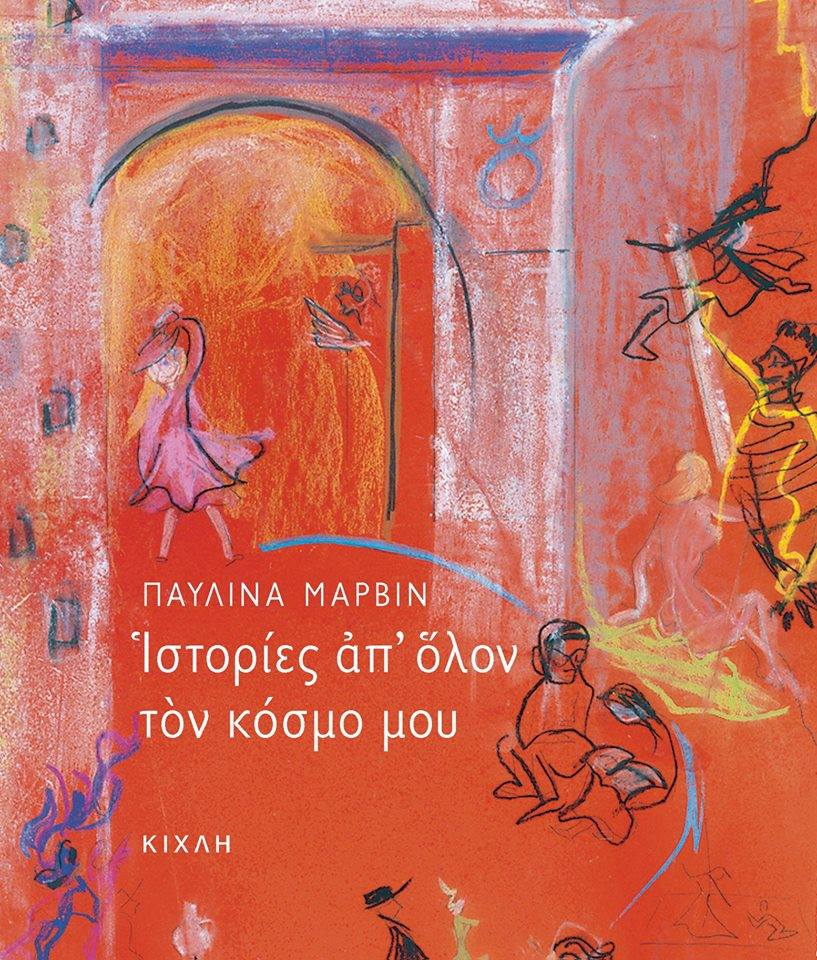

Your first writing venture Histories from all around my world received the “Yannis Varveris” Award 2018 for Best Newcomer Poet. Tell us a few things about the book.

It is a book of prose and verse, published by Kichli Publishing in 2017. It begins with the story of two little kids, who keep burying the same dead pigeon again and again, and it ends with a piece of prose poetry about the butcher’s rubber gloves lying in a mud puddle, “which know better how to say goodbye than the hand that has been my or your lot in life.” So it could be a book about the art of saying goodbye to time, to bodies, to the real, to ourselves. Or rather it is a book that wonders about the usefulness of the absurd.

How does poetry interrelate with history and memory in your work?

It is quite complicated, but if I were to simplify things, I would probably say that poetry is the medium, history provides the tools and memory offers the material. However, I feel that none of these three elements is completely, or at least largely, subject to my control, and under no circumstances would I wish to have this kind of command.

You have been a co-publisher in the poetry magazine “Teflon”. Would you agree with Thomas Tsalapatis who argued that for such ventures “the bet to be won is to bring a new audience, interested in literature yet quite distant from the art of the poetic verse, close to poetry”?

To be honest I don’t know what a “new” audience is. The audience that takes an interest in poetry, or rather in literature in general –and that being not just the writers, the students, the literary critics and other artists who deal with poetry because it is, one way or another, part of their work– seems quite unforeseen to me. As far as Teflon is concerned, I feel lucky because it shaped me and I shaped it at our starting point; I’m also happy because it is still in circulation, and I have the chance to be its devoted reader. It has been one of the first (if not the very first one) poetry magazines in our country, whose editorial team consisted basically of women, and it dealt unprecedentedly with issues that seemed to have been up to that time of no interest to the literary community in Greece. It re-approached issues from the viewpoint of a new generation –as is the case with every single generation– which carried its own expressive particularities, reversals and concerns.

Translating and discussing poems that have been written by the Aborigenes in Australia or the lesbians in Black Africa, poems from Japan, India, the Flanders, the Teflon team taught me all the Modern and Contemporary History that I had not been taught in the Department of History of the University of Athens. The only exception were the inspiring seminars of my professor, Antonis Liakos, which at that time nourished my work at Teflon, and vice versa. Of course, such topics attract inevitably a new audience, since these people have been wondering about these issues, but it was impossible from them to read neither the poems nor their literary analyses, as this kind of material had not been published regularly in any other magazine. In this sense, I understand Thomas Tsalapatis’ argument, and I believe that the bet has been won and keeps being won.

Your doctoral thesis focuses on the history of the National Book Center of Greece (EKEBI) (1994-2012). Has there ever been a national book policy in Greece? And, in turn, how pivotal is the role of a concrete state policy for the promotion of a national literature?

The National Book Center of Greece (ΕΚΕΒΙ) dealt with numerous important issues, most of which remain widely unknown. I hope that the current research will shed light on them, so that we understand not only what happened but also what is needed for the future; what’s more, it will focus attention on what has been achieved and what infrastructure projects we need in order to move on. In my opinion, there has been no national policy for the book, in the sense of setting mid- and long-term strategic goals and developing relevant investments. There have been certain individual policies, some of them more successful than others. I believe that it is of utmost importance to re-assess and develop an institutional framework in order to establish a national policy for the book. A self-regulating process cannot be expected to result in translating Greek books into foreign languages or promote the establishment of libraries or develop programs of engaged reading or protect and support the professionals of the book field or sustain a support framework for writers and their work. All these parameters should be part of a dynamic national policy for the book, as is the case in most European countries.

Which are the main challenges new writers face nowadays in order to have their work published? What role do the social media play in the promotion of new literary voices?

New writers face various obstacles but they are also recipients of certain kinds of support. As far as the Internet is concerned, accessibility and the possibility of communication are two very important gifts to all of us. Anybody can set up a blog that fulfills their aesthetic criteria at no or very low cost. However, it is noteworthy that there is no website that informs the public about the numerous literary events that take place in Athens and all over Greece everyday. Facebook is the only source of information, providing that one in touch with publishers and writers. Regarding the printed form of a work, things are considerably different. Poetry, for instance, is not high on the publishers’ list of priorities. This does not necessarily mean that the writer of a short story collection or an essayist can easily find a publisher for their writings. One must have a lot of patience, selection criteria, must be prepared for disappointment and have a plan at hand in case of rejection. In other words, one should do exactly what one does in any other kind of job. It is also true that not every writer has the same communicative skills; this does not mean that whoever has difficulty or does not systematically promote their books does not write so well as others. Actually, it could be the other way round.

One more thing that crosses my mind is the role of critique, which I appreciate and look for. I have the feeling that literary scholars, and they are not the only ones, do not read the contemporary literary production and they do not write about it. In my opinion, this fact is relevant to our general reading culture, which is linked to the Greek University syllabus. The other day I was saying to a very good friend of mine, who is a writer, that I was going to stop writing reviews about books. This is something I keep doing out of a sense of duty, because I believe that some books are worth writing for, although I do not think that I have all the necessary tools to do so. “If we don’t write about them, no one will,” was his answer, and to a certain extent he is right. Critique is constructive for both readers and writers; the former learn a great deal of things and the latter come to important realizations. However, we rarely come across this profound and systematic dimension of critique.

In recent years, there has been an extraordinary burgeoning of poetry in every form: graffiti, blogs, literary magazines, readings in public squares and buses. How is this strong civic awareness to be explained? Could poetry offer new ways to imagine what can be radically different realities?

I’m not sure that there has been a particular burgeoning in poetry. In my opinion, in every age there are remarkable poems and noteworthy poetic actions. Poetry always finds the appropriate channel. What matters though is if we are willing to reach out and connect to it, provided that we feel that we need it. I believe that poetic creation has unifying properties; it is a thread that links both the perceptible and imperceptible, the real and unreal levels of this wonder that we call ‘life.’ As Szymborska states in her poem Autonomy: In danger, the holothurian cuts itself in two./ It abandons one self to a hungry world/ and with the other self it flees. […] If there are scales, the pans don’t move./ If there is justice, this is it. […] Here the heavy heart, there non omnis moriar –/ just three little words, like a flight’s three feathers./ The abyss doesn’t divide us/ The abyss surrounds us. (https://poetrying.wordpress.com/2012/02/02/autotomy-wislawa-szymborska/)

Translated into English by Anastasia Lambropoulou

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

*INTRO IMAGE: @Antigone Davaki

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE

![Reading Greece: A tribute to [FRMK], a Literary Magazine on the Poetic Phenomenon and its Relation to Arts and Society](https://www.greeknewsagenda.gr/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/03/frmk_INTRO_1-440x264.jpg)