The year 2019 has been designated “Erotokritos Year” by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, to honour Vintsentzos Kornaros (1553-1613/14), poet and leading figure of the Cretan Renaissance, and his magnum opus, Erotokritos, telling the tale of young nobleman Erotokritos and his forbidden love for princess Aretousa. The romantic epic poem, consisting of 10,012 fifteen-syllable rhymed verses in vernacular Cretan dialect, has long been a major influence on Greek letters and arts; this influence, especially on painters of the Generation of the 30’s, is analysed here by art historian Alexandra Kouroutaki.

Dr. Alexandra Kouroutaki works as a Lab and Teaching staff (EDIP member) at the School of Architecture, Technical University of Crete. She holds a doctorate in Art History from the University of Bordeaux Montaigne, and a Postgraduate Diploma in French Literature from the School of Humanities of the Hellenic Open University, and is an honours graduate of the Department of French Language and Literature of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

Erotokritos, the masterful narrative poem written in Modern Greek by Vitsentzos Kornaros at the beginning of the 17th century, is now internationally acknowledged as a classic work of the European Renaissance. This lyrical work of Cretan literature has been read throughout Greece and loved like no other. The approximately ten thousand verses of Erotokritos uniquely convey the hues and scents of 16th century Cretan society under Venetian rule. Erotokritos inevitably became a source of inspiration for artists of the interwar period: major artists such as Engonopoulos, Tsarouchis, Theophilos, Kontoglou and others created compositions that skillfully draw on Greek visual tradition, the art of classical antiquity, Hellenistic art and Fayum mummy portraits, Byzantine religious painting, folk art, Cretan History and customs, and Greek culture in general (Kouroutaki 2018, 243-271).

We must also point out that Kornaros’ metrical epic drama has been closely related, not just with the values and culture of Crete, but with universal human values, such as personal virtue and dignity, perseverance and altruism, loyalty and passion. Particularly in Giorgos Kounalis’ paintings, the heroic figure of Erotokritos is inextricably linked to chivalry, an archetype resulting from the cultural influences on Crete through interactions with the West.

Undoubtedly, the story of Erotokritos does not define only a specific time and place. In fact, many elements of the poem, such as the medieval ambience, the Renaissance influences and the allusions to Ancient Greece are described in paintings by the artists of the “30’s generation”, depicting a timeless world, captivating in its ambiguity. Erotokritos by V. Kornaros is a token of our cultural heritage, whose significance and value transcends time and place.

Erotokritos’ journey in the visual arts begins with an iconic portrait created by Yannis Tsarouchis. The allegorical work Erotokritos (1955, oil on wood) is representative of the artist’s style and themes. Tsarouchis creates a striking, romanticised male figure, personifying the ideal of “Greekness”. “The stern full-face position of the young man, the naturalistic portrayal of the figure with clear, distinct outlines and the deep spirituality radiated by Tsarouchis’ model are all elements that evoke the Fayum portraits.

Left: Mummy with an inserted panel portrait of a youth, from Egypt, Fayum, A.D. 80–100, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Right: Erotokritos by Y. Tsarouchis, 1966, oil on panel, private collection.

The Fayum mummy portraits were created by Greek artists in Egypt between the 1st and 3rd century AD and intended for burial use, served as a prototype for subsequent Byzantine icons. Several features of the Erotokritos portrait suggest that Tsarouchis was inspired by Fayum portraits, including the large, expressive, black almond-shape eyes, the small eyelids and rounded eyebrows that meet above the nose and the short black hair that contrasts with the white garments and gold decorative elements (Kouroutaki 2018, 253).

More specifically, in painting Erotokritos, Tsarouchis employs a technique used in both Byzantine iconography and Fayum portraits: he lays brighter tones over a dark undercoat, creating tonal gradations; he uses earth colours and a basic colour palette – white, black, and yellow and red ochre (the four colours that make up the basic palette of Fayum but also Byzantine iconography), creating a variety of shades and colour harmonies.

As A. Delivorrias points out, Fayum portraits were an important source of inspiration for the great Greek painters of the 30’s generation, in their effort to interpret the long tradition of Greek-Roman and Byzantine art through contemporary lens (Delivorrias 1998, 21). Tsarouchis’ work is permeated by a profoundly Greek ambience. According to D. Kapetanakis, Tsarouchis manages to elevate a male model into a symbol of the Modern Greek spirit. (Kapetanakis, 1937, 783).

Kornaros’ narrative poem also inspired Yannis Tsarouchis’ composition Aretousa and Erotokritos (1980). The two characters’ expressive figures interestingly illustrate the psychology, social norms and gender relations during the Cretan Renaissance (Kouroutaki 2018, 254). As G. Panagiotakis points out, Kornaros’ work portrays a new female archetype, which encompasses the virtues of tenderness, modesty, nobility, maturity, courage, but also demure romantic passion (Panagiotakis, 2003, 165). Respectively, Erotokritos’ portrait is representative of virtuous youth, beauty, honour, prudence, sophistication and reliability.

Tsarouchis is especially meticulous in depicting the characters’ dress, which bear elements of style fashionable during the period of Venetian rule in Crete. Aretousa’s figure is impressive, lavishly robed in silk with a golden choker. Erotokritos’ apparel is proof that, by the end of 15th century, European dress had been adopted by the Cretan people (Kouroutaki 2018, 254) and men’s attire had been influenced by trends of the Renaissance (Spiral magazine 2010, 6). The clothes and the composition as a whole are characterized by colour balance and harmony. Colouring invokes a sensitive and romantic mood and, against the black background, it creates a particularly impressive result.

Fotis Kontoglou -one of the leading figures of the “1930s Generation”, a painter, iconographer and passionate advocate for the return of Modern Greek art to its sources- created the original illustration (1936-38) for the leather book cover of a unique edition of Erotokritos by the scholar Stefanos Xanthoudidis (1915). In his quest for “Greekness” in art, Kontoglou adopted a visual idiom rooted in iconography and Greek folk tradition.

Kornaros’ hero is portrayed as a brave warrior on horseback, armed with a sword and spear. He wears a helmet and scale armour. The figure of Erotokritos is reminiscent of the military saints in Byzantine art, as he is depicted riding a big, white horse with distinctively human eyes (Kouroutaki 2018, 255). The startled animal stands proud, bold, ornately saddled and bridled in gold with its forelegs off the ground (Kontoglou, 1996). Kontoglou’s secular art is evidently influenced by the aesthetics and methods of Byzantine religious painting.

Left: Alexandra Kouroutaki. Right: Erotokritos and Aretousa by Theofilos, 1933, organic colours on canvas, Theophilos Museum, Mytilene

Left: Alexandra Kouroutaki. Right: Erotokritos and Aretousa by Theofilos, 1933, organic colours on canvas, Theophilos Museum, Mytilene

One of Theofilos’ widely known works, Erotokritos and Aretousa (1933), makes references to the art and architecture of Ancient Greece, while at the same time highlighting elements from the culture of 16th-century Cretan society under Venetian rule. In this work, Theofilos depicts the scene from the secret meeting of his two characters, who are placed in the centre of the painting facing front. Their vibrant and expressive glances and gestures are of particular interest. Erotokritos’ posture, partly covering Aretousa’s figure, gives an even stronger sense of deep tenderness and alludes to their union.

From a morphological point of view, the work is indicative of the folk artist’s naïve-primitive technique. The technical weaknesses of the self-taught artist are obvious. But we are impressed by the brightness of the natural colours, the richness of colour tones and the contrasts. We notice the painter’s meticulousness in depicting the velvet, silk and golden-weaved period clothing, as the lavishness of dress pointed to one’s social status. The surroundings in the painting represent the “Greekness” of the landscape. The column capitals are associated with ancient Greek art and architecture, while the garden with plants and ornamental flowerpots are a direct reference to the natural landscape and customs of Greece.

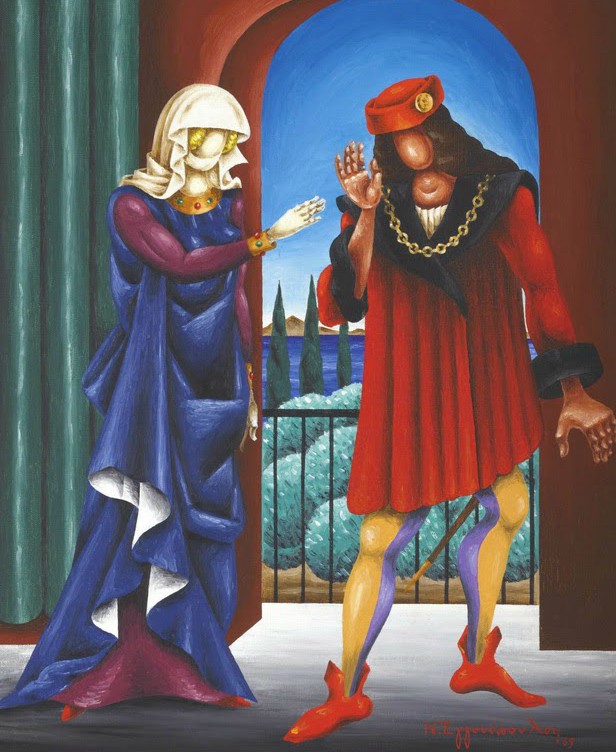

Nikos Engonopoulos depicts the meeting, and in particular the farewell scene between the two characters of Kornaros, in the oil painting Erotokritos and Aretousa (1969). It is a surrealistic and enigmatic composition that lies between dream and reality. The two protagonists are portrayed as theatre actors in a play. They are pictured as lay figures, Engonopoulos’ signature mannequins, exceptionally charming and impressive, with no facial features, dressed in fanciful period costumes, in bright and clear colours.

Engonopoulos incorporates into his painting interesting elements from 16th-century Cretan society and culture. It is widely known that Crete enjoyed a period of huge cultural and economic growth in the last two centuries of Venetian rule, now known as the Cretan Renaissance. Kornaros’ hero is portrayed as the scion of a wealthy family, his presence is imposing, and his ornate attire and sword are symbols of status and power. Aretousa, an attractive, blonde figure, is impressive with her silk garments and elaborate golden jewels, indicative of her royal lineage. The setting with the curtain is like a theatre stage, but the mountain, trees and sea in the background evoke the Cretan landscape.

Erotokritos and Aretousa by N. Engonopoulos, 1969, oil on canvas, private coolection

Erotokritos and Aretousa by N. Engonopoulos, 1969, oil on canvas, private coolection

Erotokritos was also a source of inspiration for painter, stage designer and iconographer Giorgos Kounalis[1], who had studied under and worked with the great Fotis Kontoglou. In the series of works titled Erotokritos, G. Kounalis depicts scenes from the equestrian sport of jousting, before an enthusiastic and colourful audience. Demonstrations of chivalric lance-game skills (an ancient medieval custom) had fascinated Cretans who incorporated them into their own traditions.

The works of G. Kounalis engage with a strong narrative line and convey the scene as it is described in Kornaros’ work. Erotokritos is shown on horseback, fighting with his lance against other young noblemen. In both Kornaros’ narrative poem and Kounalis’ works, the hero is portrayed as the embodiment of the spirit of chivalry, in a cultural blending of periods that combines medieval morals with the Cretan Renaissance.

In both of G. Kounalis large paintings on the subject of jousting, warm and intense colours are prevalent. In the midst of these characteristic warm tones of brown and red, impressive whites stand out, creating an unexpected colour contrast and bright result. The way in which G. Kounalis employs colour in his works is a primary means of expression and key to their understanding. Erotokritos’ victory over his opponents holds great symbolism and significance.

“When headstrong passion wills to win a race,

Wisdom will ever lag in second place;

No power has reason, nor can it strike back

When love and passion lead the same attack”

Excerpt from V. Kornaros’ Erotokritos, Canto I, verses: 267-270 (Theodore Ph. Stephanides’ translation)

In his works, G. Kounalis incorporates visual elements from different Modernist trends. In particular, in Erotokritos’ Joust (1966, pastel on paper), he uses both impressionist and expressionist techniques. In parts, outlines are well defined with a fixation on detail, in others the drawings are freer, almost abstract and forms are only suggested, while the different parts of the composition are emphasised in lively colours. The landscape, on the right, is rendered in a Cézannian manner, while the contrast between light and shade is created mainly through tonal differentiation.

In another work on the theme of Jousting (pastel on paper, 1965), G. Kounalis depicts the hero armed on a galloping horse, attacking with his lance. In this version, Erotokritos is the personification of Eros himself, as his cape takes the shape of the wings while his appearance inspires romantic love, as Aretousa emphatically states. Indeed, the omnipotence of love is a pivotal theme in Kornaros’ poem.

“Rotocritos is Eros without wings –

How was it that he lost these pretty things?

To my poor heart his wings he tightly bound,

And they obey and follow him around!”

Excerpt from V. Kornaros’ Erotokritos, Canto I, verses: 267-270 (Theodore Ph. Stephanides’ translation)

In other works, G. Kounalis presents the serenade scene. The influences from Byzantine Art, which the artist had studied in depth, are visible in these works[2]. The hero’s figure is actually reminiscent of a military saint, with dark shades used to depict the naked flesh and face. Erotokritos appears in this composition as well as the personification of Eros, the winged god of love, with his cape transforming into cupid or angel wings. In conclusion, G. Kounalis portrayed Erotokritos in compositions marked by his personal style, sometimes inspired by the rich and vibrant artistic tradition of his native land and others by the European Modernist artistic trends.

From G. Kounalis’ handwritten notes, we draw important information regarding the impact of Kornaros’ poem, his first drawings, but also his sources of inspiration. I would like to extend my warmest thanks to the family of G. Kounalis and particularly to his son, the artist Konstantinos Kounalis, for granting me access to the photographic material as well as handwritten notes from the artist’s personal archive.

“The first sketches for Erotokritos were made in 1955. Until that time, I knew little about this masterpiece of Cretan Literature, Erotokritos by V. Kornaros. […] I had heard the music and lyrics of Erotokritos, from my grandmother and my father, who sang them on various occasions. Years later in Athens, in a basement at Monastiraki, browsing through old books, I stumbled upon an undated edition by M. I. Saliveros, featuring 17 woodcuts by an unknown artist. In 1961 I went to Mystras to copy the frescoes, commissioned by the Athens School of Fine Arts. There, in the Peribleptos Monastery, seeing the military Saints so beautifully painted and with such simple materials, I was motivated to make some sketches for Erotokritos.”

In conclusion, important artists of the interwar generation portrayed Erotokritos as an archetype of the Greek spirit, in portraits and compositions with clear references to long-standing Greek artistic tradition. These works incorporate ethnic elements while at the same time highlight the unique blend of Greek visual tradition and European artistic trends of the early 20th century. This style of painting, which lies between modernity and tradition (Kotidis, 1993, 15) is part of a wider context giving rise to a cultural vision where Greek identity or Greek “archetypes” could coexist with and stand equal to the West, into which it could thus be creatively incorporated (Kouroutaki 2018, 269).

The story of Erotokritos, which presents an interesting blending of cultures, from classical antiquity, to the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, is undoubtedly not just part of the heritage of Crete and Greece, but of the entire world. In this context, the present study seeks to highlight Erotokritos’ cultural “substance” and the international appeal of the values it proclaims.

[1] Kounalis lived and worked in Chania, Crete. He was born in Neapolis, Lasithi, Crete, in 1935. He studied painting at the Athens School of Fine Arts under Moralis and Mavroidis and the frescoes under K. Georgakopoulos. He took part in group exhibitions in Greece and abroad, and has produced important art work.

[2] Kounalis, as part of his studies under Konstantinos Georgakopoulos (1960 1962) studied Byzantine Art in Mistra (1961) and later on Mount Athos (1964). The experience gained by working as an assistant to Fotis Kontoglou (1963-1964) was decisive (from the archives of the G. Kounalis family).

Bibliography

Delivorias, Angelos, Fayum portraits and the generation of the ’30s: In its search for Greekness, exhibition catalogue, Benaki Mueum, 1998

Capetanakis, Demetrios, “Yannis Tsarouchis, back to the roots”, Nea Grammata magazine, 1937

Kontoglou, Fotis, Asalefto themelio (Immovable bedrock), “Armoured in God’s armour. Saint Demetrius Myrovletes”, Akritas, 1996

Kouroutaki Alexandra, “The origins of Modernism in Modern Greek Art in the spirit of Venizelism and Crete as a source of inspiration for painters of the Generation of the 1930’s”, Kritiki Estia magazine, v. 15, (2014-18), Typocreta, Heraclion, October 2018

Kotidis, Antonis, Modernism and tradition in Greek art of the interwar, University Studio Press, 1993

Panagiotakis, George, Woman of Crete – Yesterday and today, self-published, 2003

Speira magazine, “Cretan clothing”, KETHEA, ARIADNI, Typocreta, 2010, p.6

Vitzetzos Kornaros (sic), Erotokritos, trans. Theodore Ph. Stephanides, Papazissis Publishers, 1984

Exhibition “Fotis Kontoglou. From the “Word” to “Expression”. With drawings and decorative illustrations by the author’s hand”, Nikos Chatzikyriakos-Gikas Art Gallery, 2016

Handwritten notes of Georgios Kounalis. Kounalis family archive.

Translation by Marianna Varvarrigou & Nefeli Mosaidi (Intro image: Erotokritos (Joust) by G. Kounalis, 1966, pastel on paper, Kounalis family archive.)

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Art historian Alexandra Kouroutaki on Christmas in Modern Greek painting; Fotis Kontoglou: From “LOGOS” to “EKPHRASIS”; The home and workshop of Yannis Tsarouchis οpens again; Yannis Tsarouchis: Illustrating an autobiography; Nikos Engonopoulos: The Colours of the word and the word of Colours; Richard Pine on the Durrell Library symposium “Islands of the Mind”