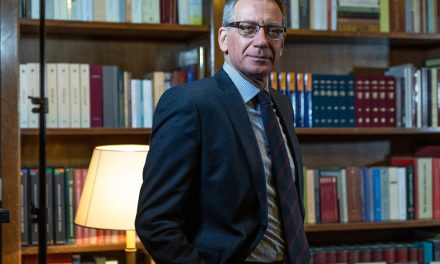

Elena Pallantza (born 1969, Athens), is a Greek-born philologist and literary translator based in Germany. She studied Classical Philology at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and continued her studies in Germany through scholarships from both German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD)and German Research Foundation (DFG). Following her PhD at the University of Freiburg, she worked as a teacher of Ancient and Modern Greek Language and Literature at the German School of Athens. Since 2003, she lives in Bonn and works at the German Ministry of Culture and Education. In 2004/2005 she pursued post-graduate studies in Intercultural Education at the University of Cologne. In 2006/2010, she was a research associate at the Department of Classical Philology of the University of Bonn, where she still teaches Modern Greek Language and Literature.

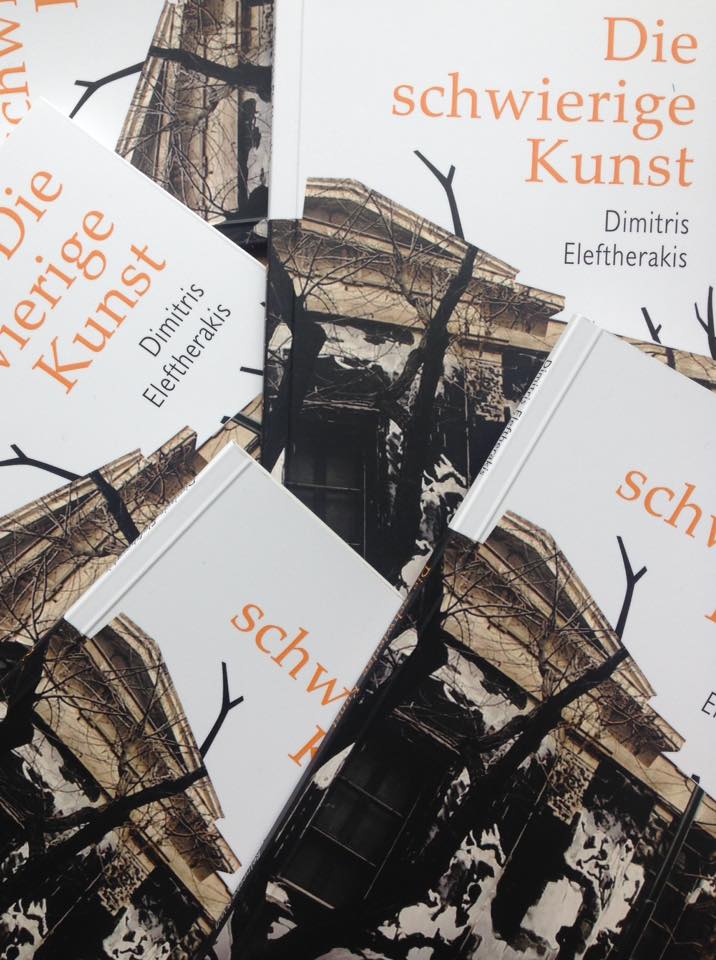

Elena writes and translates literature in both languages and lectures on Greek culture and literature around the German-speaking world. In 2016, she published her first book of poetry titled Ορυζώνος και Κυκλάδων. 25 αστεϊσμοί για μια ευτοπία (Haiku poems about the Cyclades) (Athens, Perispomeni editions). She recently formed the Translation Circle LEXIS, a team of students of Modern Greek at the University of Bonn, with whom she translates modern Greek literature into German. Her German translation of Dimitris Eleftherakis’ novella The difficult art (Reinecke & Voß 2017) received the State Prize of Literary Translation of a Greek-language work in a foreign language in 2018. She is currently translating from German into Greek the novel of Bettina Wilpert, Nichts, was uns passiert (Verbrecher Verlag 2018) as part of the litrix.de program of the Goethe Institute. In October 2020 she was a Scholar of Literarisches ColloquiumB erlin.

Elena Pallantza spoke to Reading Greece* about The Anthology of Young German Poets, which she compiled and translated, “opting for poets who try to deal with current trends in poetry and co-define them”. She also commented on “the marginalization of Greek literature in the German book market”, adding that “utilizing, connecting or supporting the individual networks of writers, translators and publishers all around Germany could be a boosting step in the long term”. As for translation, she discussed the power and responsibility of translators, noting that “literary translation is also interpretation” and that “one of the major virtues of a translator is his courage to exercise his power”. She concluded that “the promotion of Greek literature abroad without a concrete translation funding program, such as FRASIS, is purposeless” and that “it’s urgent that we built upon the positive ground that already exists, overwriting stereotypes and broadening the horizon of German expectations”.

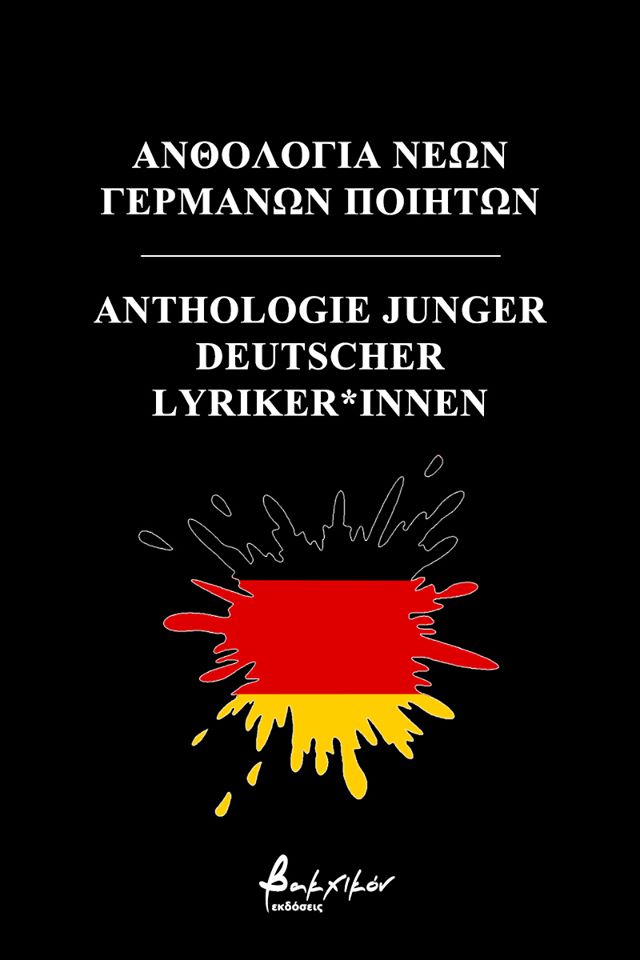

You compiled and translated The Anthology of Young German Poets (Anthologie Junger Deutscher Lyriker*Innen), which was published by Vakhikon in 2019 with the support of Goethe Institute in Athens and Kunststiftung NRW. Tell us a few things about this venture of yours.

Being part of the project young poets by Vakhikon, which aspires to bring to the fore new poetic voices around Europe, the anthology could not but have a sample as well as a personal character as in any non-thematic anthology. Following a two-year immersion into the material, I ventured, if you like, a journey into the experimental field of modern German poetry, having kept what I thought contributed to the renewal of poetic language, but chucked out a lot of what I thought was pretentious or lacking in aesthetic coherence.

I opted for poets who try to deal with current trends in poetry and co-define them. Through publications and an internet presence, journals and actions, Kathrin Bach, Sonja vom Brocke, Maren Kames, Anja Kampmann, Georg Leß, Christoph Georg Rohrbach, Tobias Roth, Lara Rüter, Jan Skudlarek, Charlotte Warsen and Levin Westermann were already actively participating in the public debate on poetry as new promising talents. Now, three years later, I am happy to see the recognition of their work in every new book, prize or translation in other languages.

It’s the generation that grew up in the re-unified Germany, under the sweeping influence of pop-culture, and came to age amid the digital revolution. They draw from their own poetic heritage but are at the same time acutely aware of what we call the post-modern condition: they explore boundaries, take advantage of any digital freedom and wittily combine the old with the new. And in this respect, they have very much in common with new poets around the rest of Europe and of course in Greece. And if anything, the anthology is meant as a gesture of poetic friendship, hopefully a trigger for further approach and interaction. As for the rest, time will show.

In turn, how easily understandable is Greek literature by a German-speaking audience? Have initiatives like Edition Romiosini and diablog.eu contributed to the familiarization of German readers with Greek literature and culture?

There are at least three things that determine whether a country’s literature can be understood by a foreign audience. The first one is its extroversion, meaning the extent to which it can speak to themes that are common across humans. The second one is the open-ness of the audience itself, its willingness to get to know the literature and culture of a foreign country. And, last but not least, it is determined by the quality of the mediator work of all those participating in the “transcription” of this literature to the foreign language.

Greek-German cultural relations are intricate as much as they are deep. At times, they have been turbulent and emotionally charged, which in a way shows that they are still an active field of exchange. In the second half of the 20th century, the presence of Greek literature in Germany had been continuous. The particularities of this era – Nobel Prizes, dictatorship, tourism, Modern Greek studies in German universities, the active presence of Greek immigrant communities – along with a plethora of translations have formed a generation of German readers with impressive knowledge and love for Greek literature and its historical and political background. But we need to realize the fact that with this generation gone we will face a vacuum already reflected in the dramatically decreased publishers’ interest in Greek works in the last few years, with just a handful of exceptions.

The marginalization of Greek literature in the German book market may have resulted either from globalization and oversupply or from the lack of a targeted policy on the Greek part. Whatever it may be, it calls us to urgently redefine our goal: What exactly do we want to “export”? What should become the cultural brand of Greece in a country like Germany in the coming decades? And perhaps more provocatively: We live in a rapidly changing and inter-connected world. Does it still make sense to define our target as promoting abroad our cultural products in national terms? Or better focus on works that are open to a constructive exchange between cultures beyond national borders?

Both Edition Romiosini, an academic publishing program that aims to create a digital archive of Greek literature as well as diablog.eu, a digital platform of varied Greek-German encounters are two different answers to the problem of marginalization. But there is also a very important space besides the two, maybe an untapped potential, quite close to the end reader, the love of reading, the analogue book: the individual networks of writers, translators and publishers all around Germany. Utilizing, connecting or just supporting them could also be a boosting step in the long term.

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this context, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie?

This argument encompasses the major question of the translatability of certain texts, especially poetic ones. As the American poet Robert Frost aphoristically comments “Poetry is what´s lost in translation“. Yet, this is after all a pessimistic view considering it focuses on what separates and not on what unites, on loss and not on gain. Let me remind you of the international glow and influence of works such as those by Cavafy or Kazantzakis – just to mention two extreme examples of poetic idiolect – where translation played an important part in their worldwide circulation.

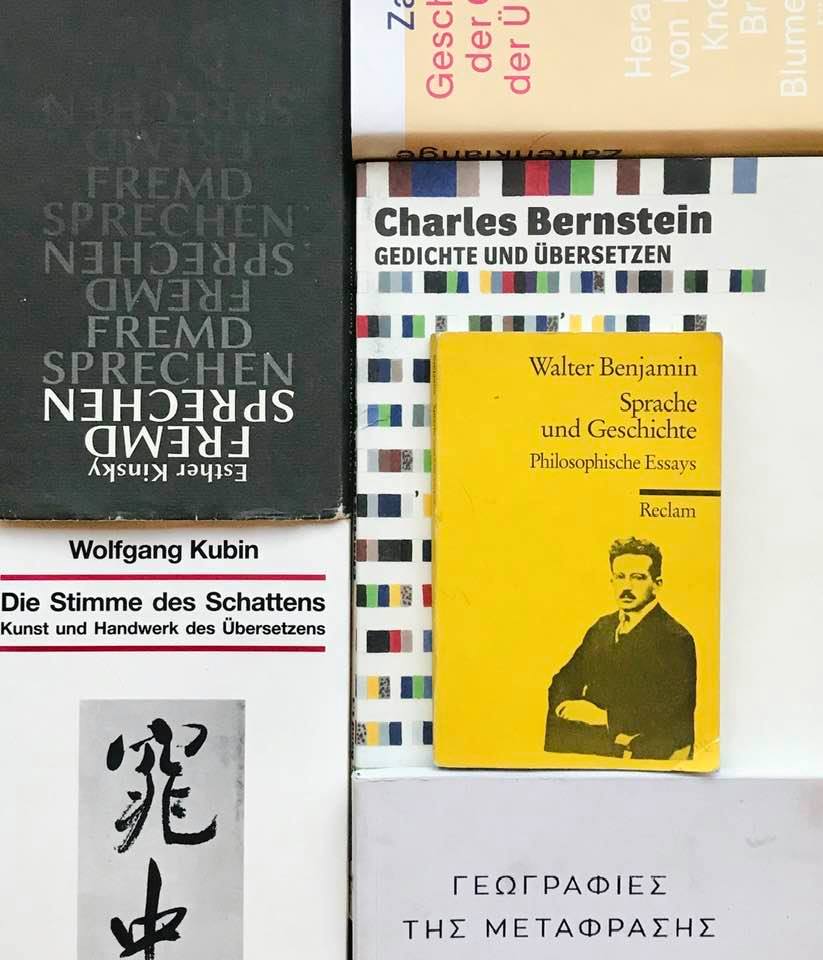

Thus, it´s a matter of attitude whether to detect the meaning of the translation process in the communication between languages, to treat the translator of literature as a participant in a unifying hyper-language, as Walter Benjamin proposes in his famous essay The task of the translator. In this case, the translator’s responsibility lies in the following: to tirelessly cultivate his spirit and his linguistic intuition; to delve deeply into the knowledge of literature and the cultural contexts of the languages between which he moves; to be fully aware that he is part of a longstanding cultural tradition and exchange, but also to not shy away from paving new creative ways in which the two languages can meet, ways that may so far have seemed impossible.

It has been argued that when translating from a so-called “minor” to a so-called “major” language or literature, translators do sometimes hold remarkable power, including the power to produce what will in many cases become the only interpretation of a work of literature available in a given language. How do you respond to this power? Can translation ever be unethical?

From the Italian play on words “traduttore traditore” (translator traitor) to the comparison of the art of translation to a “sweat delusion” by Borges or to a “high treason” by the poet-translator Odile Kennel (when Icall the tree arbre, the tree feels betrayed […]) the debate on the moral responsibility of the translator is endless. There is traditionally a widespread distrust as to his status, his intentions and his abilities. I reckon that one of the major virtues of a translator is his courage to exercise his power. When exercised virtuously, this can enrich world literature. So, the problem actually lies in the phrase “the only interpretation” and is equally relevant for any language.

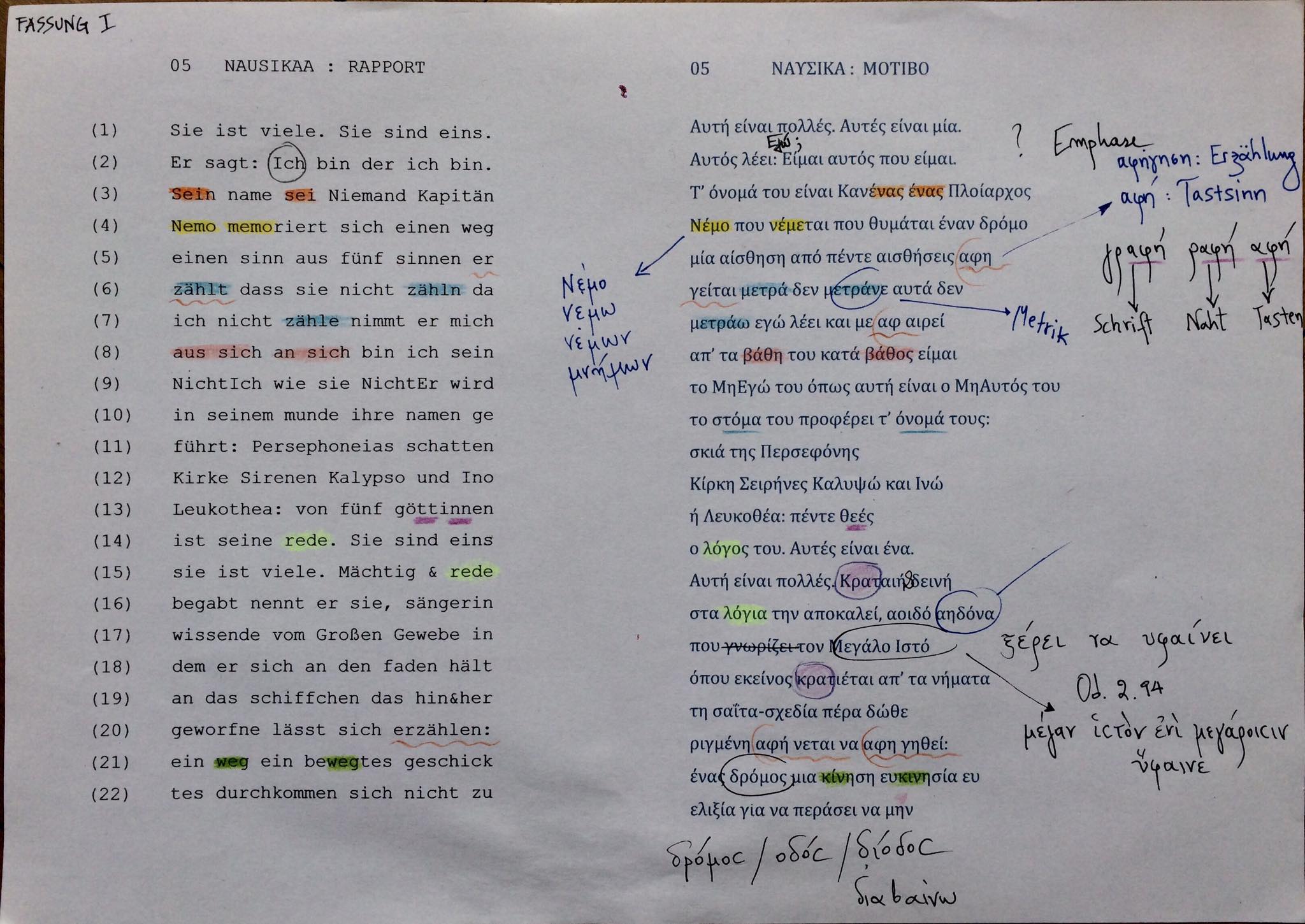

Literary translation is also interpretation. In this respect, we should accept not just the parameter of subjectivity but also that there isn’t or shouldn’t be a unique interpretation of a specific work, let alone a correct one. Just imagine a single execution of a musical work or a unique approach of a theatrical play. Translation is an open process and not a closed system with irrevocable results. That in no way means that ‘anything goes’ as to the methods, the criteria and ethics. After all, translated works are there to be judged, as works of literature themselves, and there are tools and a number of specialists to assess whether the respective choices were transparent, coherent and well-founded or superficial and arbitrary. Nowadays we increasingly notice that translators themselves are willing to open their laboratory door and reflect on the complexity of the criteria that lead to one choice over another. Yet, it’s still important to address the art of translation as what it really is: a finite act in an infinite scheme of things; an ephemeral answer given at a concrete moment, yet carrying the passionate feeling to last forever.

In an interview to Reading Greece, Michaela Prinzinger has argued that only through the development of tools that will strengthen literary translation can modern Greek literature be perceived as good literature without the need for teasers and folklore arguments. Can translators who live and activate abroad help to this end?

I fully agree with Michaela Prinzinger. The debate on the promotion of Greek literature abroad without a concrete translation funding program, such as FRASIS, is purposeless. An example of successful strategic planning is litrix.de by Goethe Institute, which is allocated to a different country every two years. Based on translation excerpts of German books selected by a joint committee of German book experts as well as those of the target country, translators and publishers may express their interest and ensure both translation funding and a contribution related to the acquisition of rights.

This strategy has something very important to show: that for a book strategy to be successful, one needs to scope people’s interest and network with the book world separately in each country. Germany does not have the same impression of Greek literature compared to Eastern European countries or the Mediterranean South. In a way, Greek literature has become here a victim of its own past success: Caught in the outmoded triangle Antiquity-Nobel-Tourism – perhaps with a recent addition of a fleeting interest due to the economic crisis – the German readers ignore considerable modern Greek works that move beyond easily digestible themes and whose reception would contribute to a more fertile knowledge of the Greek condition. Yet, there is still some kind of philhellenism among the Germans, a deep-rooted love for Greece. Therefore it’s urgent that we built upon the positive ground that already exists, overwriting stereotypes and broadening the horizon of German expectations.

Within this framework, the contribution of translators who live in the target country, who know from the inside the trends and mechanisms of the book market and have numerous ideas for a more successful promotion of Greek literature, is pivotal. In addition, they are the ones who may easier contact people and institutions related to the book market in the target country so that any literary works that have found their way into print, are not marginalized and become visible and competitive.

Could translators act as cultural ambassadors fostering understanding between different countries and cultures?

Of course, given that translation, as literature and art in general, constitutes after all a political act, an act of transcendence. By translating literature, you contribute to the spread of a country’s culture into a foreign speaking environment and thus to cross-border communication and mutual understanding. That’s why translators are often called cultural ambassadors, writers’ advocates or even literary bridge-builders between countries. Also considering the passion, voluntarism and the almost inexplicable obsession of numerous among my colleagues, I would also characterize them as romantic activists of literature.

Yet, let me conclude with afinal remark that at times, in the name of cultural mediation, the essence of translation is significantly underestimated. In the whole process of cultural exchange the literary translator mainly focuses on the creative part. His center of attention is the magic of words. Put another way, his principal mission is not a diplomatic one; he doesn’t serve any specific national interests nor is politically militant – except to the ideas of free approach. He seeks to literarily address the problem of silence of a text in a foreign language – an in itself extremely difficult and time-consuming task. In this sense it’s quite comforting to see an increasing recognition of the artistic dimension of a translator’s work, a heroic appearance out of the shadows.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

*INTRO IMAGE: @Dirk Skiba

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE