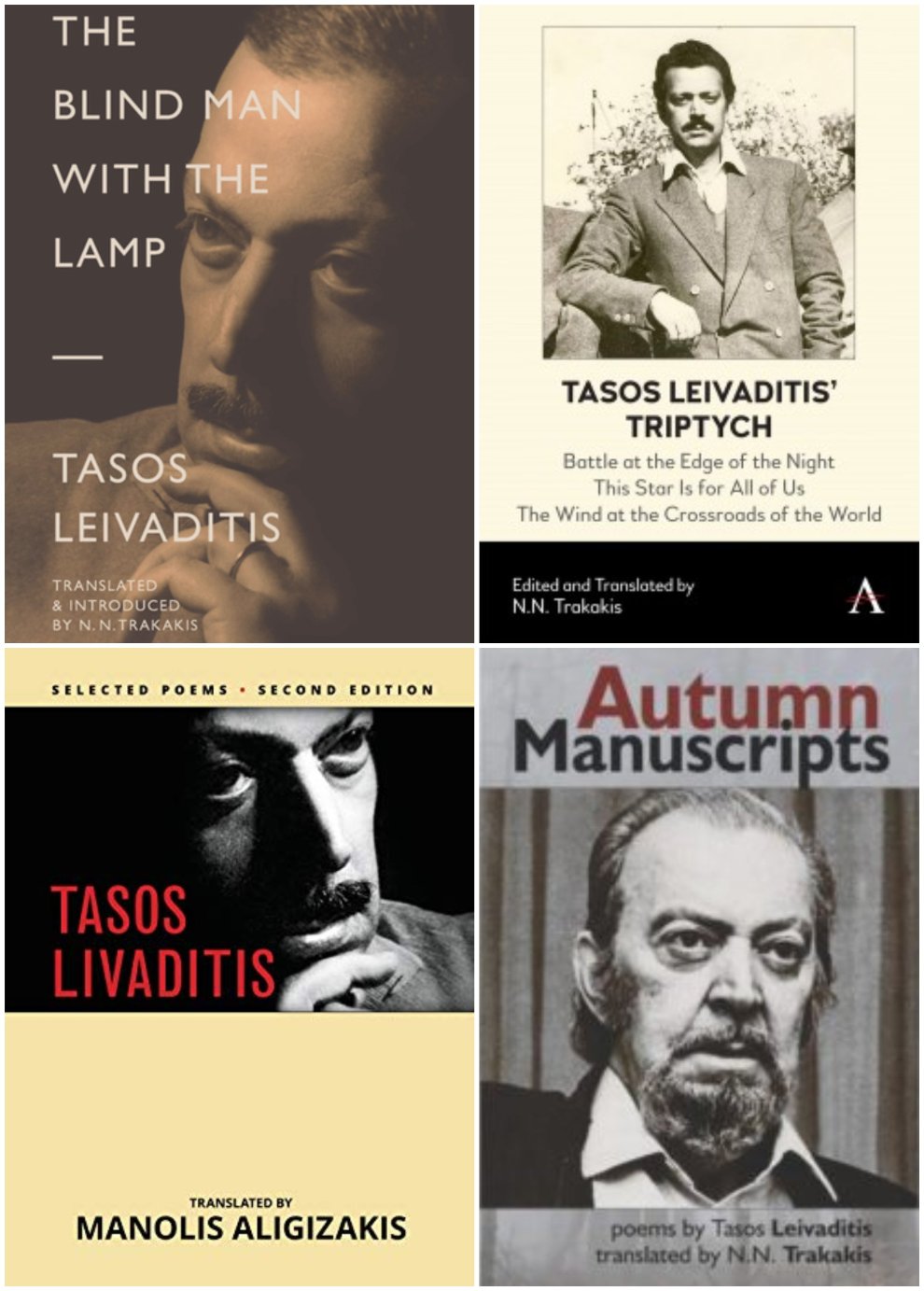

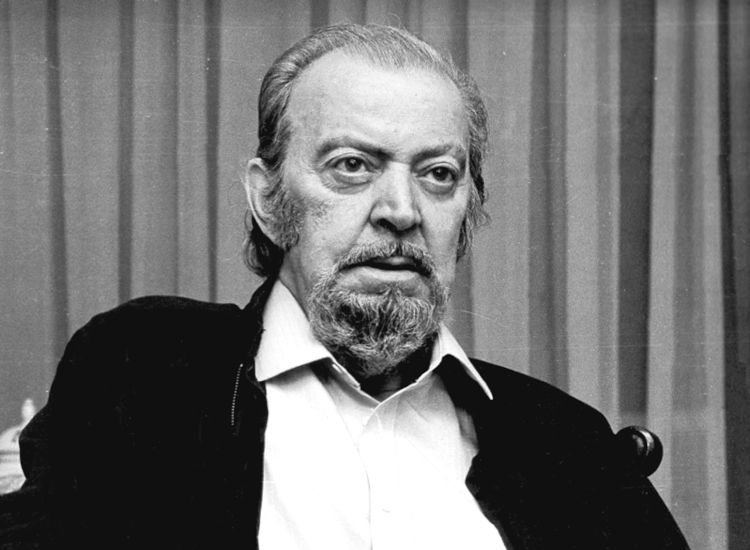

Αlthough not often discussed in the English-speaking world, Tasos Leivaditis is one of the greats amongst the postwar generation of Greek writers.

He was born in Athens in 1922. In 1940 he enrolled in the Law School of the University of Athens, but at the onset of the German occupation of Greece, in 1941, he abandoned his studies and joined the Resistance and the National Liberation Front’s youth organization EPON. After the liberation, in 1944, he continued to be politically active in the Left, which led to his exile from 1945 to 1951. He first appeared to the Greek public in 1946, through the columns of the magazine Elefthera Grammata. In 1947 he coordinated the release of the literary magazine Themelio. The years 1948-1952 he was exiled in Moudros, Saint Stratis, Makronisos along with all leftist artists and thinkers, Yannis Ritsos, Aris Alexandrou, Manos Katrakis, and many others. In 1952 he published his first book of poetry, Battle at the Edge of the Night, which consists of one long account of the anguish experienced by a soldier plunged in the depths of a night battle.

His literary output is usually divided into three periods. In his first period (1952–1956), Leivaditis develops a ‘poetry of the battlefield’ informed by his commitment to the Leftist struggle during WWII and after. In the tradition of social realism, he evokes the horrors of war but also retains an optimism regarding the future. As we move towards the end of this period his poetic lens moves beyond this specific socio-economic and political reality and fictional elements are introduced as well with a simultaneous concealment of the time and place where his long narrative poems take place, allowing for his work to become somewhat more universal.

Kantata (1960)

Plans we abandoned, decisions we feared to take

What others expected, we gave them.

We should have known there was danger in that.

As well as in what those others demanded

Though we knew they were petty, we were as well.

People we met just one night, but their stares

forever defined our lives.

Words we thought of saying, but when the moment came

Surrendered to fearful silence time upon time.

They were found at the moment of climbing the stairs,

Or in a dark-laden room, as we reached for the light.

Alone in a moon-painted room or surrounded by crowds and the light.

Where can you go then? Where can you hide? What did you do

with your unforgotten life?

[Translated by Björn Thegeby]

In his second period (1957–66), after the defeat of the Left in the civil war, existentialist concerns begin to surface and his work takes on a bleaker, more introspective tone. The poet is disenchanted, thus moving from the ‘ideal’ other/comrade to the actual one (with his compromises, his minor or major self-interests, his betrayals), as well as from the social mission from the social mission (of communism/ of revolution and poetry) to the quest of a personal identity. His book Women with Equine Eyes, 1958, was a landmark in his literary career and his turn into the introverted and existential poetry of his middle life.

The third period is considered a ‘period of introversion’ (1972-1988), during which he moves from realism, filtrated at this point through the lens of the previous existential period, to the reconstruction of reality through the use of his own, personal symbols, and from autobiography to the formulation of a poetic persona and reality, where times and places are interweaved in order to create a highly evocative atmosphere.

In the words of poet Vagia Kalfa, “throughout this course, Leivaditis moves from the idea that the poet should be socially and politically active, and from a poetry as a personal and historical document/testimony to the idea that poetry constitutes a reflection on experience, the meaning of existence and the content of personal freedom, the limits of memory and language (second period) and then to the idea that poetry is a personal transcendence/ reconstruction of reality through dreams, memory, fantasy and the unobstructed diffusion of the one to the other against the imperatives of common sense (third period)”.

Time

Then he spoke about some key.

‘How incomprehensible it is to live,’ he said.

In an adjoining room a beautiful woman was engrossed in the

mirror.

Finally he talked about a seashore, an enigma and a sick

sleeping child.

‘And then what happened?’ I asked.

I didn’t notice that thirty years had already gone by.

[Translated by N.N. Trakakis]

The Blind Man with the Lamp, originally published in Greek in 1983, is the first English translation of a complete collection of poetry by Leivaditis. A pioneering book of prose-poems, Leivaditis here gives powerful voice to a post-war generation divested of ideologies and illusions, imbued with the pain of loss and mourning. As Andy Jackson eloquently put it in his review, although “these poems read as merciless confrontations with the real”, “they are essentially elegies for existence”. From the onset, then, one is expecting a collection of poems about the never-ending search for whatever it is that makes us human, a poignant theme as much as it is diachronic.

Leivaditis’ lyrics were set to music by Mikis Theodorakis and Manos Loizos. In 1986 he published his book Violets for a Season which is considered his swan song. He died in Athens on October 30, 1988. After his death, his handwritten anecdotal poems were published under the title Autumn Manuscripts.

A.R.

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE

![Literary Magazine of the Month: [FRMK] and its Ten-Year Anniversary Issue ‘Tenderness-Care-Solidarity’](https://www.greeknewsagenda.gr/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2024/04/frmkINTRO2-1-150x150.jpg)