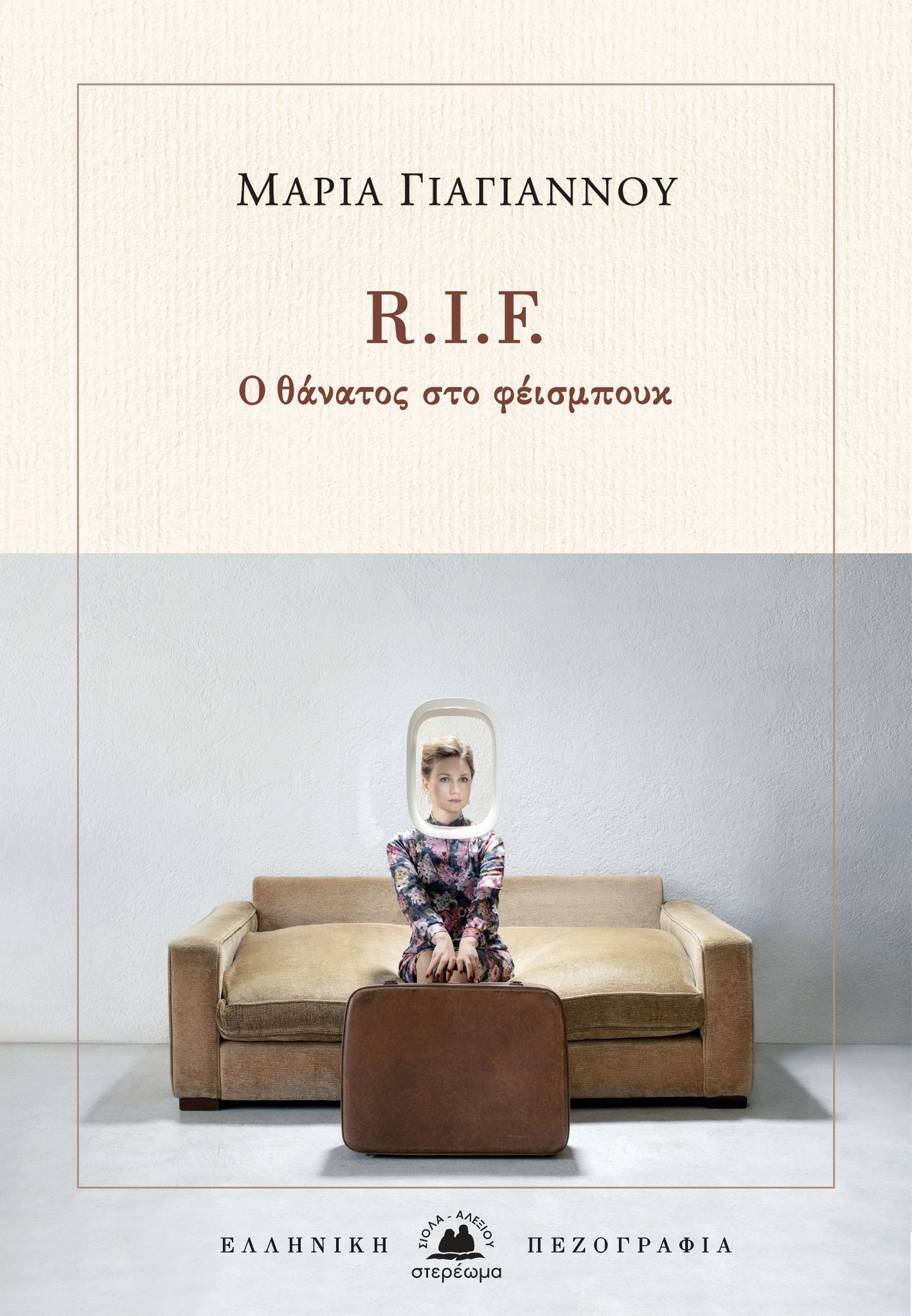

Maria Yiayiannou was born in Athens in 1978. She has published 12 books: novels, novellas, theatre plays, essays and children’s books. She studied Media and Communication at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Cultural Management at the Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, and Philosophy of Art at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. She has worked at art galleries, publicity firms, magazines, and the web radio. She curates visual exhibitions, and conducts seminars on visual civilization. From 2016 to 2018 she undertook the conception and had been the curator of the “Booknotes” (33 musical book presentations) at the Jazz Point bar, and in Technopolis of the City of Athens. Several plays of hers have been presented on many stages in Athens and also in Napoli.

Her novel The Phantom Limb (Melani Publ., 2020), which is translated in English, was shortlisted as one of the best novels of the year at the Literature Awards of Anagnostis (Αναγνώστης) Magazine and also at the Awards of Dekata (Δέκατα) Magazine – Athens Prize for Literature. Her first children’s book The Rabbit ladder (ill: C. Theocharis, Kalendis Publ., 2021) was nominated at the Awards of Chartis (Χάρτης) Magazine and also at the IBBY (International Board on Books for Young People). In 2014 she served as a member of the board of The Hellenic Center of the International Theater Institute. In her capacity as a theatrical author she participates in the project of the Acting School of the Athens Conservatoire “Humanitas/ Staging human rights of LGBTQI youth”, which will be concluded and presented in 2023. She lives in Athens with her family.

Your latest writing venture R.I.F O θάνατος στο φέισμπουκ [R.I.F Rest In Facebook] was recently published by Stereoma. Tell us a few things about the book.

Consider that in 2006 when the popular platform of our social networking opened up to every user, death was still absent from Facebook! It was only natural that at some point users would start to depart this life, as they did, but not the Internet as well… As the years go by digitally, Facebook hosts more and more obituary posts, along with very intimate mourning messages, while many profiles of users who are no longer alive continue to flourish in new ways. Ι found this conjuncture extremely interesting and thus I wanted to examine in an ‘essay prose’ way these forms of online death, using fiction as a kind of vehicle to open new paths in the analysis of our digital life. The approach is far from technophobic, but it’s definitely critical and self-critical.

The body of the text is made up of reflections, which, however, maintain a functional role and are read in sequence and as a whole to help keep the track. The book’s title (R.I.F. stands for “Rest In Facebook”) is a pun on the acronym R.I.P. (Rest in Peace) which we often post to say goodbye to someone who has passed away. The title is a good guide to the subject of the book without, however, testifying to its various dimensions, such as the reflection on the future of writing and the decline of quality interpersonal communication.

How drastically have the notions of life and death been transformed in the era of online communication?

Life is the succession of our days, which means that it cannot possibly be postponed; it’s happening even when we think some days are just parentheses to something bigger. But the life of our life is the meaning we give to our every day. I reckon that in the era of digital communication meaning is fragmented, like our attention. Our inability to focus and delve deeper can reduce our endurance in spiritual aspects of life that require patience, time and self-concentration. For instance, the super teen Tik-Tok is a disturbingly disruptive platform – bursts of silly videos to death! To answer your question: death does not change, it is not affected by anything, it is a cessation of images. But we can avoid the living death that is the obsessed relationship with every screen, a mockery of loneliness that can desolate you inside.

“Life on social media is a kind of auto-fiction, which means that it offers a second chance of existence to a lot of people. Yet, it still remains a distorted life”.Τell us more.

By following the peculiar way of post-writing and by posting photos on the social media we participate in a spectacular party, which at times resembles a conference, at others a court, a demonstration, a poetry anthology or a polyphonic school yearbook. It is therefore an impressive tool, which provides liveliness, information, ease of (first level) communication, and sharing of experiences. It indeed offers to many people the opportunity of a second birth, an autogenesis, where the self projects itself as it wishes, even if it significantly differs from… itself! I’m OK with all of these as long as they don’t break our innermost mirror, the constants our mirroring is worth finding: love, the body and its senses, the fertile silence somewhere outside the party.

What role do the social media play in the way people read and write? How can writing be safeguarded in a metaverse universe?

The opinion I share through R.I.F. The death of Facebook is that the social media in which writing still survives as a means of interaction (which is not at all self-evident in the immediate future), trains daily the way we think, since the material of our thinking is, primarily, words. Every day we teach ourselves to write in specific contexts, based on unspoken rules (usually about popularity and digestibility), as we become advertisers of either ourselves or our text.

Conventional reading has been dramatically reduced, book sales are low, turning the page feels heavy for a huge number of people. But at least I still hope that when the social media are completely immersed in the universe of digital images (as Metaverse promises), a number of people will seek spiritual harmony and aesthetic beauty back in the material, traditional treasure called book.

Prose, theatre, children’s books, essays, among artistic ventures. What is the binding thread?

All my writings are inputs-outputs. The thread that unites all my texts has on one end the immersion in the soul and on the other end an escape to imagination. It is, so to speak, a psycho-aesthetic eye that I cast upon things. I want to go deep and study the sensitive dark and bright aspects of human psychology, as well as to reach the figurative heights of linguistic imagination. My books are gestures of communication, which wish to seduce the reader, adult or child, towards some areas where a pleasurable feeling of carefreeness coexists with knowledge.

“Words are my eyes, so I’ve never had to switch to writing – it’s always been my way of seeing myself, the world, art”. What role does language play in your writings?

Words may be an inadequate system, but they are our way of defining our thinking, of reflecting. I’ve personally learned to (think and) figure out what I’m thinking by keeping a diary – endless conversations with myself to understand my feelings have saved me from many meltdowns and gotten me through crises unscathed.

Regarding literature, I am not of the opinion that language is only a medium. I believe it is also a message. Depending on its wording, the very same thought can be read as a cliché or as awesome originality. It’s one thing to say “everything is random” and another to say “a roll of the dice will never eliminate the random” (Stephane Mallarmé). The richness of our language is an inexhaustible asset. I don’t’ appreciate verbalisms or an obsession with language – the older I get, the more they bother me. Yet, I can’t help but consider each author’s writing style – understanding and reading pleasure, how it resonates with me, all depend on the language their soul speaks.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE