“The light of Greece opened my eyes, penetrated my pores, expanded my whole being”

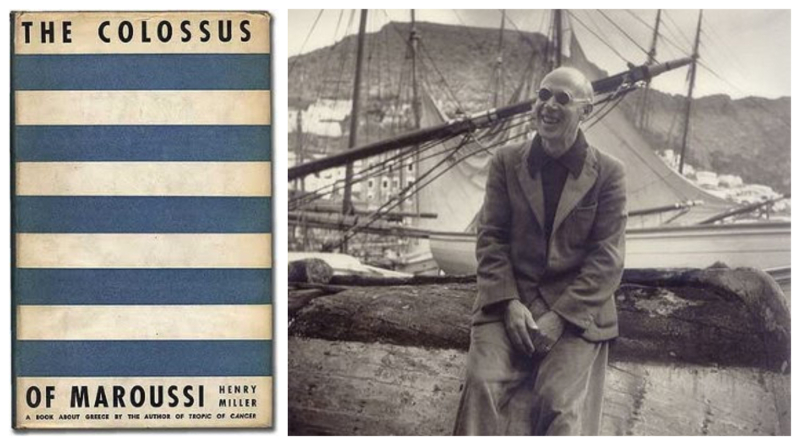

Henry Miller, The Colossus of Maroussi

Henry V. Miller (December 26, 1891 – June 7, 1980) was born in Yorkville, NYC. His life is chronicled both by himself through his books and by his fellow authors. During his lifetime he had to fight mediocrity and poverty, working at many mundane jobs. He started to write in his 30’s. When he discovered Europe, particularly Paris, he became friends with writers like Anais Nin, Alfred Perles and Lawrence Durrell. In the 1930’s he wrote and published Tropic of Cancer, Black Spring, Aller Retour New York and Tropic of Capricorn. He also painted watercolors although he never considered himself a real painter.

The Colossus of Maroussi is an impressionist travelogue, first published in 1941 by Colt Press of San Francisco. In 1939 Henry Miller travelled to Greece from Paris, where he had been living at the time, at the invitation of Lawrence Durrell, who lived in Corfu. During his 9-month stay, he traveled across Corfu, Athens, Poros, Hydra, Spetsai, Epidaurus, Mycenae, Crete and Delphi. The Colossus defies the linear style of a travel narrative. The description of cities, archeological sites and landscapes is interrupted by taverna scenes and by Miller’s rambling and ranting about western civilization, the press, technological advancement and revolution.

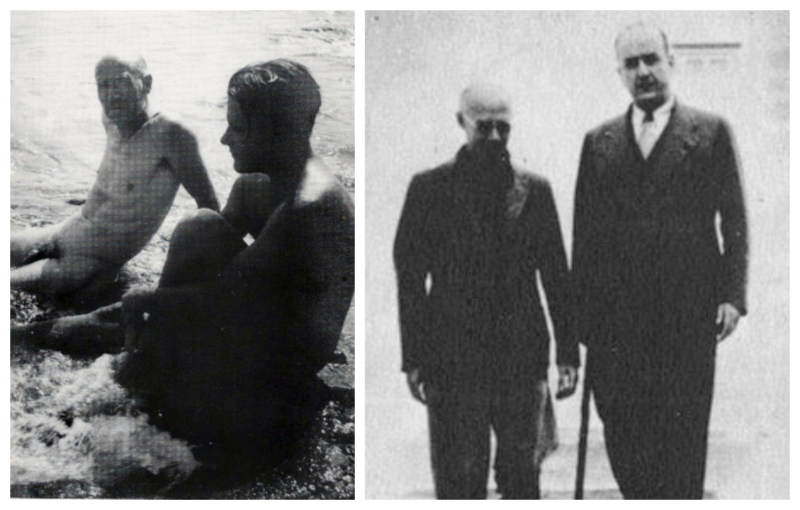

(Left) Miller with L. Durrell, Corfu 1939 (right) Miller with George Katsimbalis

(Left) Miller with L. Durrell, Corfu 1939 (right) Miller with George Katsimbalis

Through Durrell, he met and befriended some of the most emblematic representatives of the group of poets, artists and intellectuals that became known as the Generation of the ’30s. It is in Athens, a city “still in the throes of birth”, against the “light and splendor of the Attic landscape”, that Miller makes the acquaintance of intellectual George Katsimbalis, the 1963 Nobel Prize winner George Seferis and of painter Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas. The war was on but forgotten in the company of those men. The trips and the evenings shared among them in tavernas, between intellectual conversations, fine food and lots of rezina, render The Colossus a book on friendship.

Miller attributes to his friends and their work many characteristics that considers quintessentially Greek. Katsimbalis, the “Colossus” of the title, is passionate, a bon vivant with a strong sense of the tragic. As he talks “unhurried, unruffled, inexhaustible and inextinguishable”, he grows out of his human proportions, becoming a Colossus. Ghikas is a “seeker after light and thruth”. Seferis is, according to Miller, the man who has caught and embedded in his work “the spirit of eternality which is everywhere in Greece”. Seferis’ passion for his country is, for Miller, a special and thrilling peculiarity of the intellectual Greek who has lived abroad. When Edmund Keeley, an emeritus professor of English at Princeton and prominent translator of Modern Greek poets, interviewed Seferis for the The Paris Review, he noticed that whenever Seferis began to reminisce about friends from the war years and before—Henry Miller, Durrell, Katsimbalis—he would relax into his natural style and talk easily until the tape died out on him.

The Generation of the ’30s. In the middle, Seferis, standing and Katsimbalis, seated

The Generation of the ’30s. In the middle, Seferis, standing and Katsimbalis, seated

Miller had not received any classical education. His idealizing the Greek character and landscape and his tendency towards mythmaking may at times seem over the top and naïf. Soon though the reader realizes that it is more of an internal landscape that Miller so emotionally describes and that his journey is one of rebirth. As the British essayist and novelist Pico Iyer observes: “the Colossus marks the moment when Miller, then 47, quit the cheap cafes and after-midnight streets of Paris and begun reconstructing himself, without apology, as a latter-day Transcendentalist”.

“And what is it about Greece that makes you like it so much?” asked someone.I smiled. “The light and the poverty”, I said.“You’re a romantic”, said the man.“Yes,” I said, “I am crazy enough to believe that the happiest man on earth is the man with the fewest needs. And I also believe that if you have light, such as you have here, all ugliness is obliterated. Since I’ve come to your country I know that light is holy: Greece is a holy land to me.”[…]“You can say that because you have sufficient…”“I can say that because I’ve been poor all my life,” I retorted. […] “It isn’t money that sustains me– it’s the faith I have in myself, in my own powers.”

The book takes us to a Greece that no longer exists. There is in fact a sense of paradise lost. And as Keeley remarks in his book Inventing Paradise, the Greek Journey 1937-1947, it was the work of the Greek poets themselves that, even more than Miller’s travel memoir, best conveyed that sense, as the world war cast a number of them from the Aegean and scattered them to the earth’s four corners.

Read more via Greek News Agenda: Of Greece and Ireland: An enduring friendship; Meet “The Durrells” in Idyllic Corfu!; Bookshelf: Anglo-Hellenic Cultural Relations

Lina Syriopoulou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS