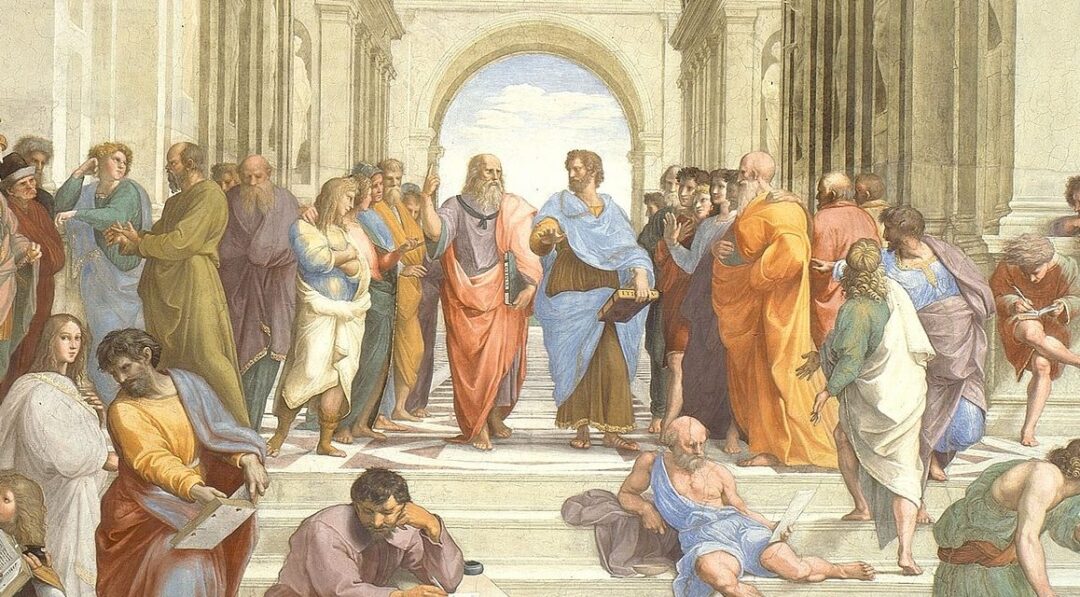

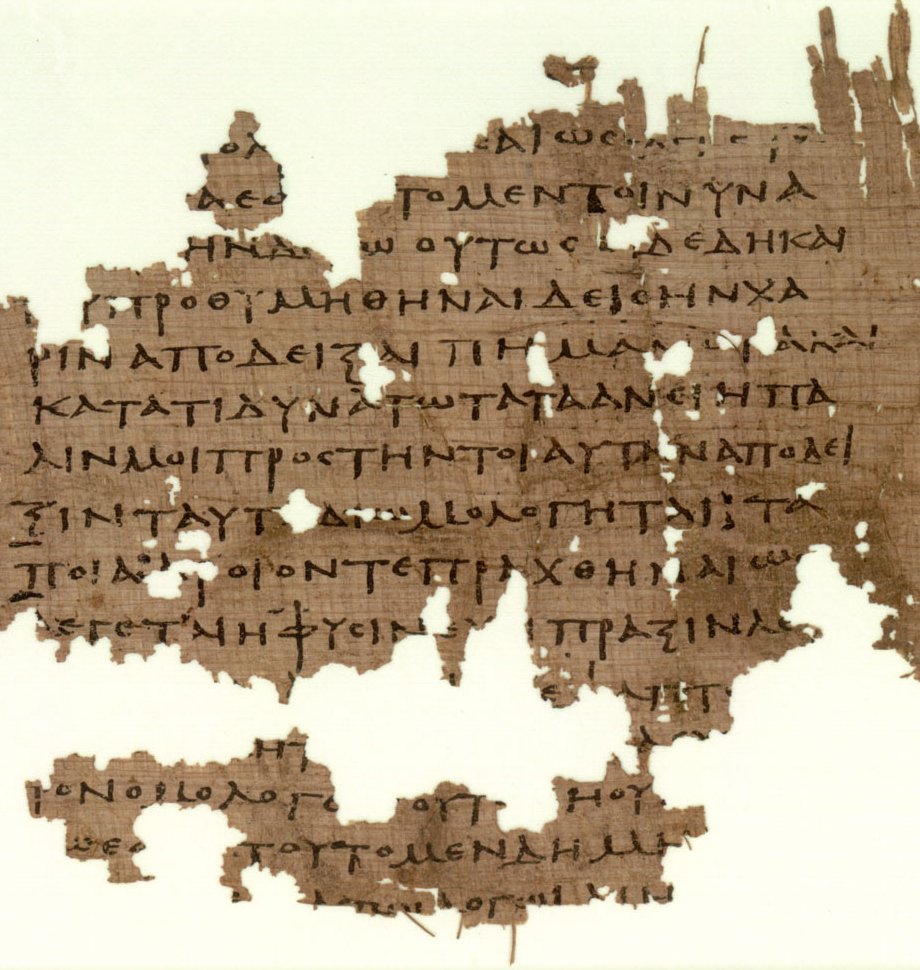

Born around 2450 years ago in Athens to a prominent family, Plato—originally named Aristocles—would go on to become one of ancient Greece’s most influential thinkers. His encounter with Socrates at the age of 20 was a transformative moment, shaping his intellectual journey profoundly. In 388 BC, after a formative trip to Sicily, he founded the renowned Platonic Academy, often considered the first university in the world. Among its students was Aristotle, who subsequently became the esteemed tutor of Alexander the Great. Plato’s dialogues, the primary medium for his writings, exemplify his pursuit of wisdom and understanding. In a time when philosophy was more about seeking wisdom than establishing dogmas or factual certainties, Plato’s ideas hold enduring significance. We will try to explore Plato’s philosophies and their implications on contemporary global affairs, shedding light on how the love of wisdom can offer insights into navigating the complexities of our interconnected world.

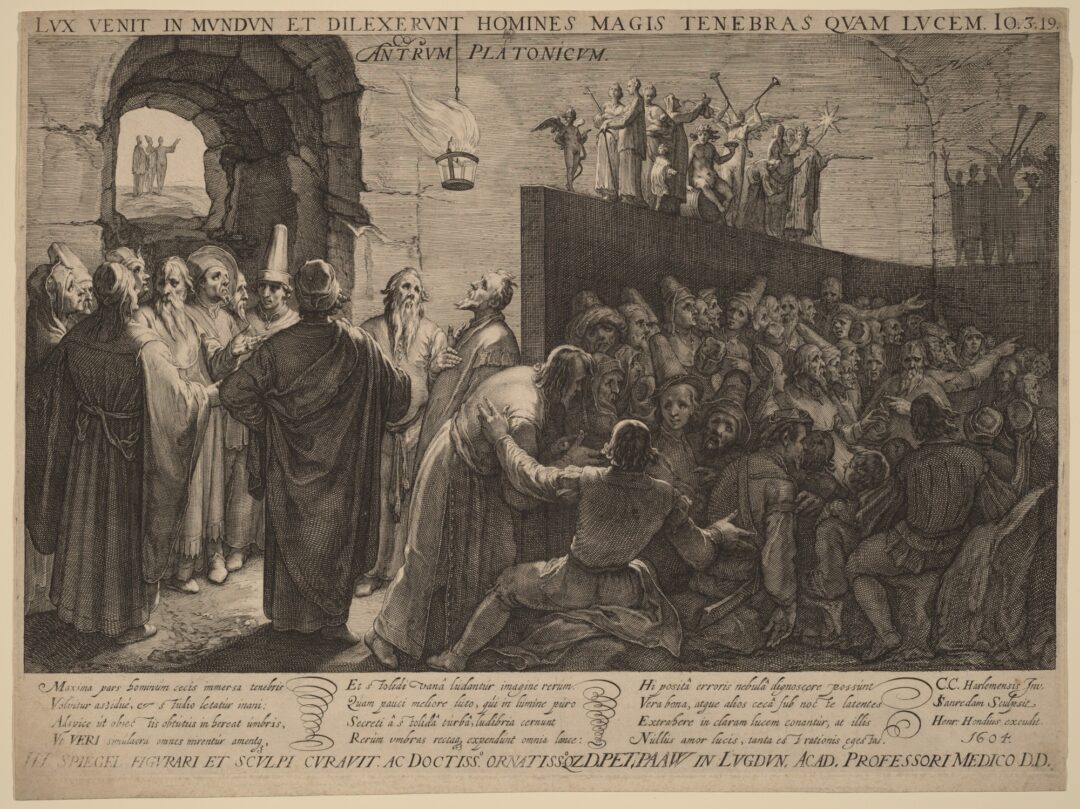

Plato’s “The Cave”

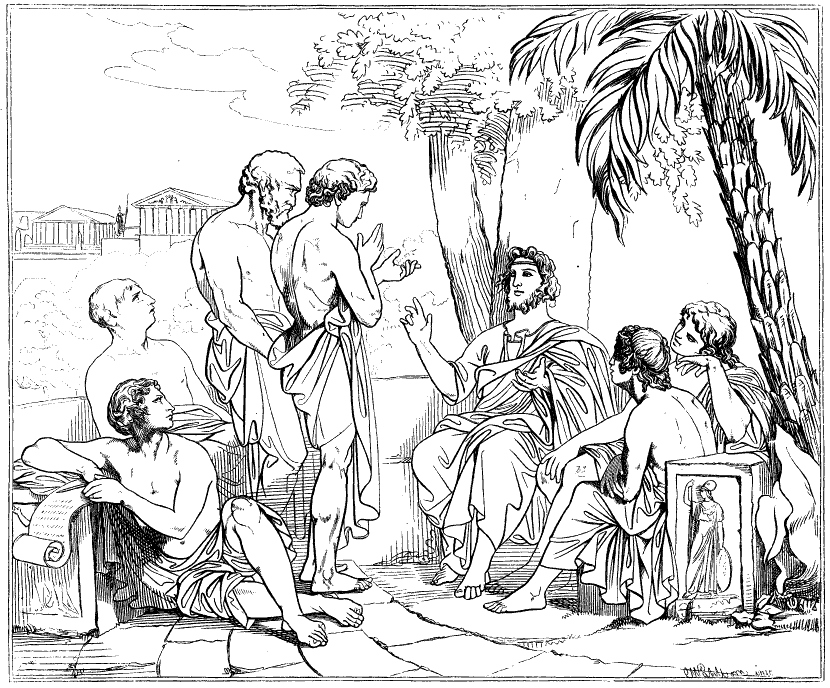

Plato’s allegory of “The Cave,” found in Book VII of his seminal work The Republic, is an exploration of human perception and the quest for true knowledge. Like all of his works, it takes the form of a dialogue with this being between Socrates and Plato’s brother, Glaucon. In this allegory, Plato presents a vivid scene where prisoners are confined to a dark cave since birth; their legs and necks bound, they are only able to see shadows cast on the cave wall by a fire behind them. Unaware of the outside world, the prisoners mistake these shadows for reality and consider them the only truth. However, when one of the prisoners is freed and forced to venture outside, he encounters the blinding light of the sun, symbolizing the world of true knowledge. Initially overwhelmed, the liberated prisoner gradually grasps the profound insights of the real world.

Upon the prisoner’s return to the cave, eager to share his newfound understanding of the outside world, he finds himself met with skepticism and ridicule from the other prisoners. They are reluctant to believe in a reality beyond the familiar shadows they have grown accustomed to and dismiss his revelations as mere fantasies. The prisoner’s struggle to convey his experiences highlights the resistance to change and the difficulty of accepting profound truths that challenge established beliefs. Plato’s allegory marks the philosopher’s gradual path to knowledge. It serves as a poignant commentary on the human condition, illustrating the reluctance of many to embrace knowledge and enlightenment, preferring the comfort of ignorance and the familiar confines of their perceived reality. It underscores the importance of critical thinking, open-mindedness, and the willingness to question conventional wisdom in the pursuit of genuine knowledge and enlightenment.

Plato’s Virtue

Central to Plato’s philosophy was the idea that Virtue is not innate but could be cultivated through knowledge and education. According to Plato, everyone is born virtuous. The distinction between a virtuous individual and an unvirtuous one, according to Plato, lies not in their desire for what they perceive as good, as both seek goodness. Rather, it is predicated on their understanding of what genuinely constitutes the good. Virtue, in this context, becomes intricately linked to knowledge, while evil is rooted in ignorance. Plato contends that virtue extends beyond mere moral goodness and encompasses excellence in every facet of life: actions, thoughts, and intentions. Consequently, virtuous conduct emerges from a profound grasp of the true essence of goodness, while evil actions are borne out of a lack of genuine understanding.

In The Republic, Plato expounds upon the four cardinal virtues, which occupy a central position in his ethical theory and underpin both individual moral character and a just society. These cardinal virtues consist of Wisdom, Courage, Temperance, and Justice. Each virtue plays a distinct and vital role in shaping human conduct and fostering the harmony and integrity of a well-ordered community. Plato’s exposition of these virtues serves as a framework for understanding the essence of ethical excellence and the path to a virtuous and equitable society.

Plato accords Wisdom (Sophia) the status of the supreme virtue, as it encompasses the capacity to pursue and grasp truth while using knowledge in a just and beneficial way. For Plato, wisdom surpasses mere intellectual expertise; it entails a profound comprehension of the world and the faculty to discern between good and evil, right and wrong. Philosophers, in Plato’s view, exemplify wisdom, as they devote their lives to the pursuit of knowledge and the contemplation of eternal truths. By celebrating wisdom as the pinnacle virtue, Plato underscores the significance of rational inquiry and moral discernment in cultivating virtuous individuals and fostering a harmonious society rooted in profound understanding and ethical wisdom.

Courage (Andreia) represents the virtue of bravery and unwavering resolve when confronted with fear, danger, or adversity. Plato emphasizes that courage does not entail the absence of fear but rather the ability to confront it and act virtuously in challenging circumstances. Significantly, courage is intricately linked to the preservation of the entire city or society, as individuals possessing this virtue are willing to safeguard the community’s well-being, even at the risk of personal harm. In Plato’s vision of the ideal state, courage finds its embodiment in the guardians—the ruling class—who exemplify unwavering bravery by defending the city and upholding its fundamental principles with steadfastness. Through the cultivation and celebration of courage, Plato stresses the value of fortitude and resilience in establishing a just and harmonious society, safeguarded by individuals committed to the collective welfare.

Temperance (Sophrosyne), synonymous with self-control or moderation, is the virtue of mastering one’s desires and emotions. Plato argues that the human soul has three parts: reason (logistikon), spirit (thymoides), and appetite (epithumitikon). Temperance arises when reason assumes governance and harmonizes the other two parts. It entails exercising control over bodily desires and impulses to attain inner equilibrium and harmony. Plato regards this virtue as crucial for an individual to achieve a well-ordered soul and contribute to the establishment of a just society, underscoring the importance of self-discipline and balanced behavior.

Justice (Dikaiosyne) occupies a paramount position in Plato’s ethical framework, serving as the cornerstone upon which the other three virtues rest. It is the virtue of granting each individual their rightful due, upholding principles of fairness, truth, and righteousness: a just society materializes when each person fulfills their role in accordance with their innate abilities and talents. In this ideal city-state, Plato proposes a tripartite division of labor, with philosophers as rulers, warriors as defenders, and producers as the working class. Each class is expected to act justly and fulfill their societal duties for the city to function harmoniously. Plato posits that a just individual is one whose reason governs over their spirit and appetites, fostering a well-balanced soul. In The Republic, the political notion of Justice corresponds to the harmonious balance of the three classes (philosophers, warriors and producers), while the moral notion to Justice corresponds to the balance of the three parts of the human soul.

Plato’s Republic

Rooted in a series of dialogues involving Socrates and his interlocutors, Plato’s Republic centers on the pursuit of justice and the establishment of an ideal state governed by philosopher-kings (king here means ruler not monarch). Key among its themes is the allegory of “The Cave. ” Plato contends that the majority of individuals reside in a state of ignorance, akin to the prisoners confined within a dark cave, perceiving mere shadows of truth. True wisdom, he posits, emerges through philosophical contemplation, transcending the illusory realm of sensory experiences to ascend to the higher plane of abstract Forms.

In the process of constructing an ideal city-state, Plato introduces a tripartite division of the soul, comprising: logistikon (reason), thymoeides (spirit), and epithymetikon (desire). This conceptual framework elucidates the nature of justice within the individual, emphasizing the necessity of achieving internal harmony by allowing reason to govern over the other elements. This concept of a harmonious soul parallels the harmonious organization of the ideal city-state, wherein distinct classes—rulers, auxiliaries (the protective class), and producers (the working class)—are assigned specific roles to cultivate social harmony and the collective good.

Integral to Plato’s vision of the ideal state is the concept of philosopher-kings, who possess true wisdom and virtue. They serve as the enlightened rulers, leading the city with a profound understanding of the Forms and a commitment to the pursuit of the greater good. The rulers are individuals possessing knowledge, expertise, administrative abilities, and moral uprightness.

Plato further explores the critical role of education in shaping virtuous citizens. He proposes a system of early moral and intellectual training, advocating for children to be raised collectively by the state. He explains how good art can lead to the formation of good character and make people more likely to follow their reason. Physical education should be geared to benefit the soul rather than the body, since the body necessarily benefits when the soul is in a good condition.

Notably, the Republic also scrutinizes different forms of governance, categorized into five types of regimes: aristocracy, timocracy, oligarchy, democracy, and tyranny. Through this analysis, Plato highlights the inherent vulnerabilities and strengths of various political systems. He ultimately contends that the most stable and just state is one guided by the philosopher-kings, wherein the pursuit of wisdom and reason shapes the city’s ethos.

Plato’s aspiration was to create an ideal society based on the principle of specialization, where individuals would excel in specific fields according to their merits.

Ultimately, Plato’s Republic presents a philosophical exploration of justice, knowledge, governance, education, and the human soul. Richly woven together through dialogues and allegorical narratives, this seminal work continues to captivate scholars and philosophers alike, provoking ongoing contemplation and discourse on the enduring questions of human existence and the ideal society.

This is an article taken from Greece In America, the official newsletter of the Embassy of Greece in Washington. (Intro photo: Statue of Plato at the Academy of Athens [by Edgar Serrano via World History Encyclopedia])

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Beyond Socrates – Greek philosophers you might not know; Plato’s Academy today; Cornelius Castoriadis, thinker of autonomy; Common words you (probably) didn’t know were Greek – Part 4

TAGS: HISTORY | PHILOSOPHY