Ioanna Lioutsia was born in Thessaloniki in 1992. She is a PhD researcher on Performance Art in Balkans (University of Peloponnese). She holds an integrated master degree in Directing (Theatre department, AUTh, 2018), a BA in Acting (Contemporary Theatre Drama School, 2017) and a BA in History & Archaeology (AUTh, 2014). She works as an actress, director, dramaturg and drama teacher.

Your latest writing venture Wide Vowels and Bitten Consonants was recently published by Thraka. Tell us a few things about the book.

Wide Vowels and Bitten Consonants were published in spring 2022. Ιt’s my fourth poetry collection, which comprises 40 poems written up to 2019. The title of the collection comes from an orthophony lesson and concerns the correct articulation of actors. By moving the phrase from the theatrical context to the poetic, I felt it could take on many and interesting connotations that converse with the poems in the collection. In other words, I wanted, through these poems, to be able to articulate some of the things that we bite and swallow, clenching our teeth and lips in our daily lives, whether they concern politics and society, or e.g. love and interpersonal relationships.

Poet Nikolas Koutsodontis has characterized your poetry as that of “a young person living in a world without hope, impoverished, emotionally narrow, where poets are wandering defeated, while at the same time hailing the polemics of love as a way for art to move forward”. How does your poetry converse with the world it inhabits?

My poetry is a child of its time, but also of its region. Μy themes, my stories, the faces and personae of my poems are inspired from the world in which I live. I believe that, just as nothing in nature is created in a vacuum, so poetry and the themes that concern us and are expressed through it cannot appear autonomously. Even if I speak of love, I cannot do so without somehow considering the spatio-temporal simultaneity in which this love occurs. I think it would be kind of hypocritical to do so, as if turning a blind eye. I mean that even Romeo and Juliet, the most mythologized and ultimate literary love affair, took place within a specific context. In another context the same people would be different and so would their love.

But before we even get to romance and love, I am afraid that our age is opposed to any kind of friendly mood and attitude of solidarity, to any expression of tenderness. We live in a world where everything familiar and safe tends to disappear. I believe, and especially in the days to come, that all we have is each other and all together art – any kind of art – to turn darkness into light and power. As Archilochus says in a translation by Giorgos Blanas “Life is tamed with songs”.

You have published four poetry collections so far. Which are the main themes your poetry touches upon? What role does language play in your writings?

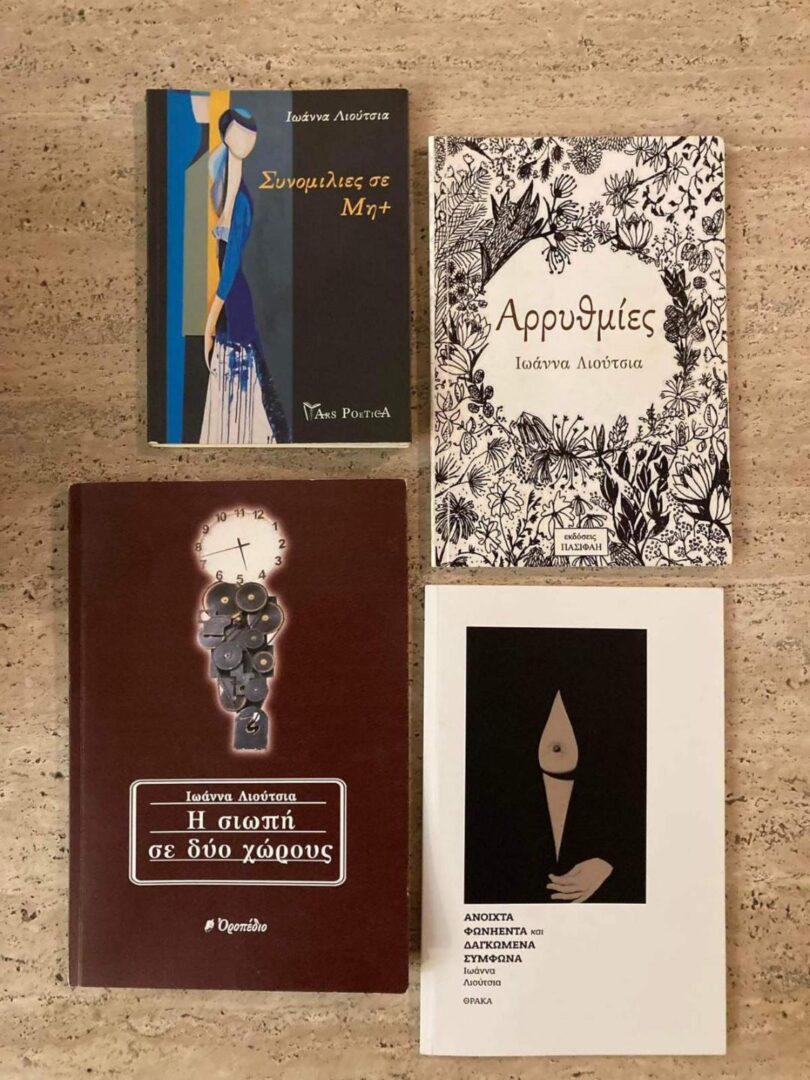

I think there is a constant in the themes that interest me but at the same time a gradual evolutionary path in the way they are expressed in each collection. The dominant theme in the first collection, Conversations on Do(n’t) Major, is love but also the admittedly difficult transition to adulthood. This “cry” of the 20-something years, as Rilke would say, gives way in the second collection, Arrhythmias, to a more conscious management of life, loneliness, social non-acceptance, romantic reconciliation and an identity search. In Silence in two spaces I am concerned with all the previous themes, while poems about gender issues also begin to appear. This leads to the most recent collection where all the above themes appear, but with a tendency towards their socio-political dimension, a fact that I realize more as time goes by than when I was writing them.

When it comes to language, I’m inclined to the verse of George Seferis, “I want nothing more than to speak simply, to be given this grace.” I consider it difficult but necessary to create a poetic language with rhythm, with metaphors, new words, puns, etc., with whatever one may want, but which is based on a modern, living, everyday language. I want to use a language that expresses us, the now we are living. A linguistic element that really fascinates me, however, and is present in quite a few of my poems, is the etymological games or misunderstandings that can be created by homophones.

You are part of ‘Grafoules’, a collectivity of female poets, who organize actions – usually unexpected ones – on the street, writing ‘poetry in a state of emergency’. Tell us a few things about this venture of yours.

The idea for ‘Grafoules’ existed as a seed both in my mind and in the mind of the poet Pavlina Marvin. In May 2022 in a discussion to prepare the presentation of my collection, we realized that we were both excited by the idea of poetry on the street, the idea of the poet’s direct social contact with the world, the idea of poetry functioning as a way to touch on certain issues that concern us at the time that they concern us. We also recalled our love for ‘grafoules’, toy typewriters on which we used to write as children, and that’s how we got our name. As “Grafoules”, we are always interested in the playful dimension of the challenge of writing a poem in three to five minutes. Our first action took place last March in Syntagma Square together with Danae Sioziou, Nanti Chatzigeorgiou and Wichi, writing poems both on a typewriter and by hand. Each poem is written on the spot after a conversation with passers-by and is offered for life to the unique recipient who inspired its creation. We continue trying to have a monthly presence each time in a different place in Athens, without excluding our presence in some other city in the future.

Βeing an actor, dramatist and director, where does poetry meet the theatre in your work? Would you say that they two constitute communicating vessels?

I would say it is something even more. It is a large container with different fountains. From each fountain comes something different that takes the form of either a poem, a performance, a play, etc. Whatever I want to say, I feel it finds the most appropriate medium to express itself. Some things I write, others I want to act in, others I direct and so on. Many times, a theatrical hero, a line from a play, an orthophony lesson as I said above, can act as the trigger for a poem. In addition, I characterize my poems as autobiographical and experiential not because I have necessarily gone through all the situations and emotions that appear in the poems myself, but because many times I try to observe the people around me and empathize and write about their stories, about their own experiences and feelings. Even if it’s about experiences that I’ve actually only lived in my imagination!

This kind of observation of the people around us is also an essential tool for people involved in theatre, whether as directors or actors. After all, both poetry and theater speak, each in their own means and ways, about common things: about everything that concerns humans. In turn, poetry also supplies the theater with material. In the Theater Department of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, in order to get introduced to directing, I did not direct a play but a poem by Takis Sinopoulos. I also borrow titles derived from poems to plays and performances, and as a dramatist I am interested both in the poetry of the theatrical language, as well as in the harmonious integration of verses or entire poems in it, in a way that it is not perceived as a foreign body.

In the last few years there has been an extraordinary burgeoning of poetry in every form: graffiti, blogs, literary magazines, readings in public squares. How is this strong civic presence to be explained? Could poetry offer new ways to imagine what can be radically different realities?

I reckon that this ubiquitous appearance of poetry, its intense social presence has a lot to do with the fact that we young poets have grown up in a state of continuous crisis. Personally, I came of age when the first memorandum came to Greece, but already a little earlier you could feel the turmoil due to the collapse of the banks in the USA. From 2010 until today, 13 years later, poets a little older and a little younger than me have only experienced periods of successive crises. If we have learned anything from these crises is not to expect anything from anyone; it’ us that we have to create it, and create it in unison. For these reasons, I believe that we have turned more to ways of direct communication with the world through the presence of poetry in the public space, but also its stronger presence in social networks, bypassing more traditional ways of presenting poetry and poets, in an attempt to put into practice the verse of poet Titos Patrikios “poetry finds you”. I think most of us today don’t think that poetry is for the few and chosen, so through our actions we try to change this well-rooted impression.

I used to think that art could not change the world. What I believe now is that perhaps only art, in all its aspects, can achieve that and this is why I am also very interested in children’s contact with literature, theater and the arts. Poetry and art will not provide solutions, but they can move your thinking on certain issues. Especially in times of crisis when people tend to become introverted and “guarded”, I think this strong presence is important, as it shouts “we are not alone”. And the response that all these actions, posts on social networks, e-magazines, etc. have, let alone the choice of a graffiti verse, shows that yes, indeed, “we are not alone”.

How do young writers and artists converse with global literary and artistic trends? Where does the local meet the national and the universal?

It is a given fact that nowadays more easily than ever we can have access to both the literary and artistic production of almost any country in the world, as well as to the printed and online media that present and promote it. This undoubtedly enriches our artistic universe, while at the same time strengthening the presence of contemporary poetry in translation in our country, given the great number of translations of contemporary and unknown poets in our country that have been published in recent years in online and printed magazines. There is always something to discover out there and it definitely makes you feel like maybe not everything has been said after all. Although all poets through their poetry are undoubtedly influenced by the place in which they live and write, I consider that the universal elements of writing exceed the local element. I am interested in and can be fascinated by a poem from Iran without experiencing the everyday life that women face there, in the same way that I am also attracted to an American poem.

I believe that poetry transcends borders and that is why there are translations of foreign poets in our country or cooperations of Greek poets with foreign magazines and websites, maybe even with publishing houses. Beyond the specific and the local, what poems aim for is the creation of a feeling, an atmosphere, an idea, an emotion, etc. What people can feel is common, even if their stimulus is different. After all, with so much information at our disposal, we are able at any time to have at least some basic knowledge about the socio-political contexts in which a poet works. These contexts, too, may not be so unrelated to our own reality after all, as we operate globally on the basis of the butterfly effect.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE