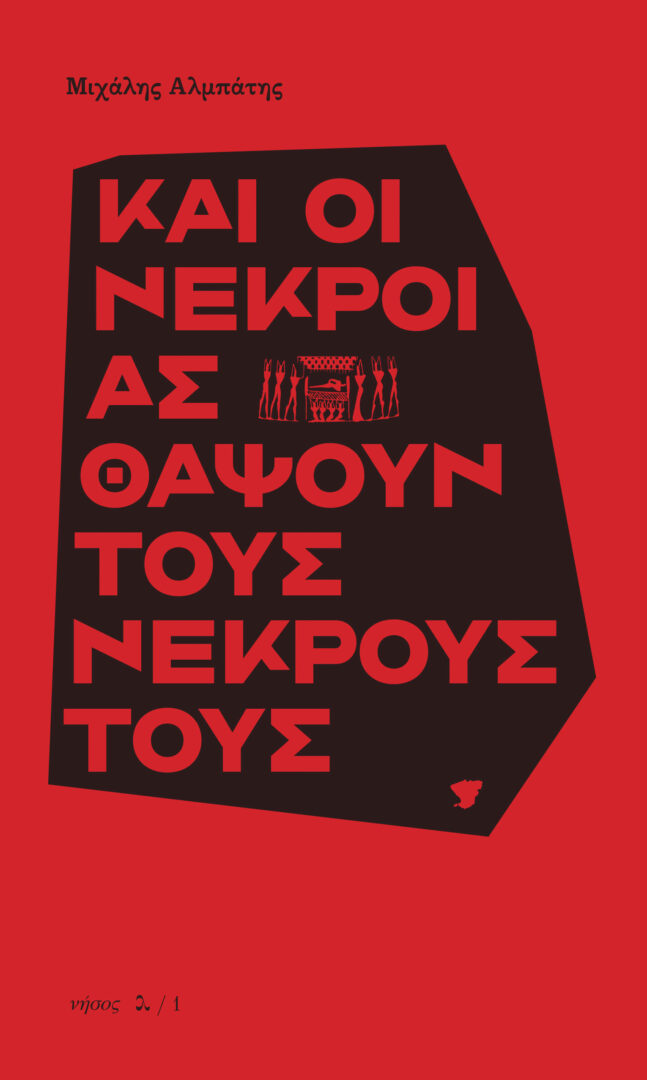

Μihalis Albatis was born in 1973, in Zaro, a village in the foothills of Mount Ida and lives in Heraklion, Crete. He published his first novella in 2018. His first novel, Και οι νεκροί ας θάψουν τους νεκρούς τους [Let the dead bury their dead] received quite favorable reviews upon publication.

Your latest writing venture Let the dead bury their dead (Nisos, 2022) received quite favorable reviews upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book.

The story begins in a mountainous village of Crete, in the early 1950s, when a fifteen-year-old boy, going to a funeral for the first time in his life, discovers that he can listen to the thoughts of the dead, the whispers of the soul through the relic where it remains trapped. Of course, no one believes him, but when he reveals something that only the dead person knew, everyone is convinced. Ιt is then that an uncle of his decides that they can earn a lot of money from this rare gift of young Fanouris. So, they start, on a donkey and a mule, to tour the villages of the plain offering their services as “interpreters of the language of the dead”.

We could say that it is a novel of wandering and coming of age, with many frame stories, all those narratives of the dead who, having been freed from every convention and every shyness, feel the need to reveal what they have kept hidden a whole life.

The “now” of the book is the early 1950s, but with the stories-memories of the dead we travel even further back at times “when the world was not yet completed disenchanted”, as you said. How does the past interweave with the present in the book?

The world today is completely disenchanted and Fanouris, my hero, would have no place in it except as an inmate of a mental hospital. In those days, on the contrary, people still believed in ghosts, fairies, witches and elves; after all, all myths, of all peoples, were born not in the city but outside, in the rural communities, where people still had roots in the land, where they still conversed with the weather, the plants, the animals. If art turns to the past, always with the risk of beautification and idealization, it is to find that breath of the mythical that a strictly technocratic culture has so brutally deprived us of. Humans cannot live without myth.

“I write about the comedy and drama of the human condition”. Which are the main themes you delve into? How interrelated is death with life and love in the book?

The dead in my book don’t worry so much about the afterlife; they find it strange that they’re still there, tied to their remains, but they don’t deal with issues of immortality and eternal life. They have the incredible opportunity, through Fanouris, to speak to their own people, and they are burning with the need to say what they didn’t manage to say, what they didn’t dare say all these years. Thus, they talk about “eternal issues”, about everything that has never stopped and will never stop preoccupying humans, about love of course, in all its manifestations, from the romantic, platonic to the wildest manifestations of lust, about devotion, loss, faith, guilt, loneliness, the search for truth, freedom. Humor and love dominate the pages of the book because these are the only antidotes we have against death, and the dead advise the living not to be frugal in their expression.

What about language? What role does language serve in your writings?

There are people who argue that language is simply a means to tell a story and should not prevail in importance. The question is certainly a balance between structure, content and style, but in the end, it is the latter that unifies everything, that keeps them together. And while every story can be told in a myriad of voices, as Queneau beautifully shows in Exercises in Style, there is ultimately only one of them that can highlight the essence of the narrative, enliven the text, and that the author should discover. This is why the first pages of a book are so important, because they reveal whether the author has found the ideal language; from then on, the bet is to succeed in serving it until the end.

Which are the main challenges new writers face nowadays in order to have their work published? What role do the social media play in the promotion of new literary voices?

It is quite difficult for new writers in Greece to see their work published. It takes patience, perseverance, luck. I was trying for ten whole years until I managed to publish my first book and The Dead waited for more than five years in my drawer. Even if you do succeed, it’s very difficult to make your book stand out from the flood of new releases. And all this becomes even more difficult for people, like me, who live in the countryside, without acquaintances, connections, etc.

Social media indeed constitute an alternative route to promote your work, as readers, without intermediaries, can exchange opinions and share their “discoveries”. Reading Clubs also play a major role, a phenomenon that flourished since the pandemic; it is a very promising development for the promotion of the love of reading.

How does literature converse with the world it inhabits? Could it be used to imagine what could be radically different realities?

This is the magic of literature. There is no other art that can speak so directly and so deeply about the reality of humans, integrating history, philosophy, sociology, psychology, aesthetics, contemplation and emotion. Through it we can see aspects of the world that we otherwise wouldn’t have access to, we can perceive creation through the eyes of a child, a criminal, a wise man, a madman, a saint. Literature is a tool to understand the world and other people around us, but also to reach unknown depths of ourselves.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE