Asteris Huliaras is Professor of Comparative Politics and International Relations in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at the University of the Peloponnese, where he holds the European Jean Monnet Chair on EU relations with Less Developed Countries. His research interests focus on (global) North-South Relations, development studies, foreign policy analysis and civil society.

Professor Huliaras is the author or editor of several books and articles in peer-reviewed journals, including African Affairs, Asia-Europe Journal, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, and European Foreign Affairs. Among his recent publications are ‘Civil Society’, in The Oxford Handbook of Modern Greek Politics (2020), and with Kostantinos Magliveras, ‘African Diplomacy’ in The Sage Handbook of Diplomacy (2016). He has served as an advisor of the Greek government on public policy, in the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs and in the Greek Permanent Mission in the United Nations, while also having served as an expert in NATOs Expert Working Group on Africa and in the United Nations Human Security Network.

Professor Huliaras spoke to Rethinking Greece* on Africa’s prospects in the 21st century; on why EU’s interest for Africa is on the rise; on the evolving dynamics of the relationship between Europe and Africa and on the contacts, synergies and networks that are being created and strengthened between Greece and sub-Saharan Africa. Finally, he talks about the EU project he is the scientific director of, AfriquEurope, the largest network of African and European universities in the field of social sciences.

At the beginning of the 21st century, Africa was deemed to be at the point of economic take-off, and its geopolitical power was on the rise. Where does Africa find itself in the international geopolitical and economic landscape now?

By the turn of the century, optimism abounded regarding Africa’s prospects. By 2000, six out of ten countries with the highest growth rates in the world were African. At that time the continent experienced unprecedented, since independence, levels of peace, with an increasing number of African leaders elected through largely free and fair elections. Global interest in African affairs surged, notably marked by China’s emergence as a leading trade partner, aid provider and investor in the continent.

However, this optimism has since dissipated. Much of Africa’s growth was tied to the soaring international prices of oil, metals, and other primary products. Consequently, when these prices plummeted, African exports suffered. While some resource-poor countries benefited, their gains were short-lived. The onset of the pandemic exacerbated existing challenges, compounded by civil wars in the Horn of Africa and Islamic rebellions in the western Sahel. The eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo remained mired in near-permanent crisis. These developments collectively displaced over 20 million people. Though several countries, such as Kenya, Ghana, and Cote d’Ivoire, exhibited relative resilience and maintained impressive growth rates for long periods, the overall landscape has markedly shifted. Numerous coups d’état, particularly in the Sahel, democratic regression (even in traditionally free nations like Senegal), and escalating conflicts that now threaten to destabilize entire regions have tarnished African prospects.

Still is difficult to generalize. Next to failures you have important success stories (e.g. Burundi versus Rwanda). Africa is more diverse than Europe. As the title of a recent book suggested: “Africa is not a country.”

How would you describe the Europe-Africa relationship today, and what are its prospects? How is it affected by factors such as the new Samoa agreement or China’s dynamic presence in the continent?

In the past 5-6 years, developments concerning the future of EU’s relations with Africa are, at a first glance, disappointing. After BREXIT, Africa lost one of its strongest champions in Brussels. Then, the pandemic struck and EU’s attention focused on domestic health challenges. Finally, a week after the EU-African Union summit on 17-18 February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine. Several analysts pessimistically concluded that Europe’s focus is shifting from Africa to other parts of the world. But then, in the past 5-6 years we witnessed several diverse messages and developments. In 2019, just before the last German election, Angela Merkel proudly argued that EU’s “policies on Africa, now follow a common strategy, which a few years ago would have been unthinkable”. In March 2020, while Europe was closing down in response to the coronavirus, the new European Commission released a new communication entitled “Towards a comprehensive Strategy with Africa,” a document with plenty of new ideas and plans. And finally, in December 2021, the EU announced the €300 billion so-called Global Gateway investment strategy – a very ambitious project, similar to the Chinese Belt & Road Initiative. Half of it – this means 150 billion euros – is to be deployed in Africa. Details of the Africa-Europe program, the first regional plan under Global Gateway, were announced just two months after the launch of the strategy.

So, there is no doubt that despite BREXIT, despite the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, increasingly EU officials and EU member-states are looking towards Africa. In my view, there are several factors that explain EU’s growing interest for Africa, leading to a much closer partnership. The first factor is a growing understanding that tackling underlying security and migration challenges would require a more holistic approach towards Africa. The second factor is the realization of the need to respond to Europe’s loss of influence amidst the growing number of external actors showing an interest in Africa, especially – but not only – China: India, Brazil, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Iran have all become important actors in Africa. The third is an understanding of the huge opportunities for European businesses that might arise from supporting Africa’s adoption and implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement and the new Samoa Agreement. Finally, in a strange way, the Ukrainian crisis has also increased Africa’s geopolitical importance for the EU. Both the EU and Africa focus on energy and food security. Among others, cooperation with some African countries is expected to help Europe replace imports of Russian natural gas and reduce dependence from Russia.

How can Africa complete the trajectory from a recipient of development aid to an equal partner with Europe? What do African countries expect from Europe?

Over the past half-century, the shadows of colonialism have gradually receded, paving the way for a shift towards what the European Commission terms a “partnership of equals” in Europe’s engagement with Africa. Amidst this evolving landscape, there is a growing desire among Africans for increased European “greenfield” investments and greater support for infrastructure development across the continent. Additionally, there is a call for enhanced mobility opportunities for Africans seeking to relocate to Europe. While some authoritarian leaders may resist European pressure for liberalization and democratization, many African civil activists advocate for the EU to take a firmer stance, imposing stricter sanctions in response to human rights violations.

Thus, while the dynamics of the relationship between Europe and Africa continue to evolve, there remain tensions between the aspirations for a closer economic partnership and the imperatives of justice and accountability. Migration is also a constant challenge for policy-makers in both sides. Africa continues to be much dependent on both development aid and access to the developed world’s markets (especially for agricultural products). There is no doubt that to a large extent and despite the rhetoric, the relationship remains asymmetrical. However, this does not mean that African countries are powerless. There is much African “agency” in EU-African relations.

How does Greece differ from the rest of Europe in terms of its relations with sub-Saharan Africa? Which countries are of particular interest to Greece?

There has been a great deal of diplomatic activity taking place within the last 5 years in Greek-African relations. Greece has opened a new embassy in Senegal and former foreign minister Nikos Dendias made several official visits to the continent. Much of these contacts relate to Greece’s ambition to be elected as a non-permanent member of the UN’s security council for the 2025-6 period. There is also a push to do more, due to Turkey’s advance and rising influence in Africa. So, the main reasons for the Greek-African rapprochement are political.

At the economic level, if we look at Greece’s trade of goods with Sub-Saharan Africa, numbers are still insignificant. However, there are reasons for optimism. Firstly, there is a “hidden” economic activity, not very well recorded in statistics, that has to do with trade in services such as shipping, consulting, etc. Secondly, the Greek business community, encouraged by the Hellenic-African Chamber of Commerce and a few diplomatic missions in Athens (like the South African Embassy) shows a renewed interest for investing in the continent. For example, Mytilineos Group is investing in Libya and Ghana. Thirdly, diasporic communities (Greeks in Africa and the rising number of Africans in Greece), universities, NGOs and various cultural groups undertake numerous initiatives that are largely fragmented and difficult to monitor, but are however gradually and continuously fostering a wider, closer and deeper Greco-African relationship. Contacts, synergies and cooperations are multiplying, and many new networks are created and strengthened between Greece and Africa.

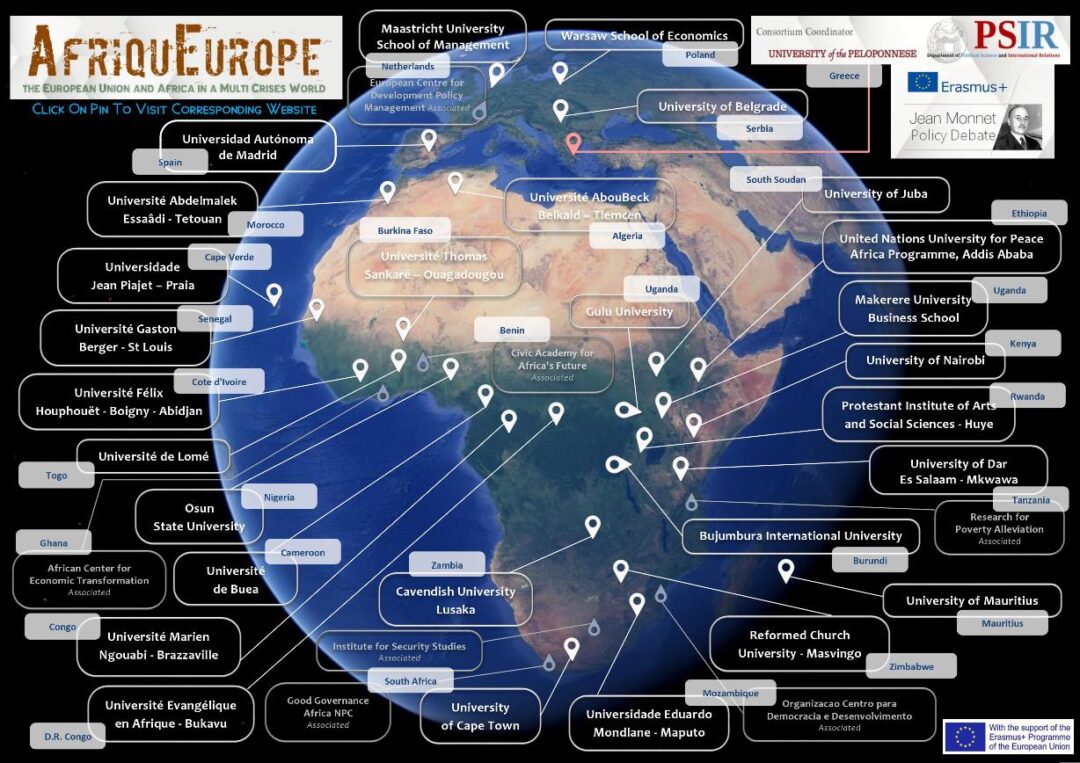

You are the scientific coordinator of the European Commission project “AfriquEurope: The European Union and Africa in a world of multiple crises,” which aims to support closer cooperation between the two continents. Can you tell us more about this project?

We are very excited about this project. With partners and collaborators in 33 countries representing all regions of Africa, including French-, English- and Portuguese-speaking countries, AfriquEurope (2024-7), funded by the European Commission – Jean Monnet Policy Debate, is the largest network worldwide of African and European universities in the field of social sciences. With the University of the Peloponnese as the lead partner, the project will organize 12 thematic conferences in Africa, Europe and China as well as 10 research groups that will produce books, articles and working papers on EU-African relations. As the world order is being reshaped, AfriquEurope is dedicated to a mutually reinforcing dialogue between Europe and Africa, aiming at deepening ties and creating evidence-based solutions for policy makers on both sides of the Mediterranean.

* Interview to Ioulia Livaditi

Read also from Rethinking Greece:

- Angelos Dalachanis on the Greek Diaspora in Egypt and the Middle East

- Alexander Kitroeff: “Greek Diaspora has affected the history of host countries around the world”

TAGS: EU POLITICS | GREECE-AFRICA RELATIONS | INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS