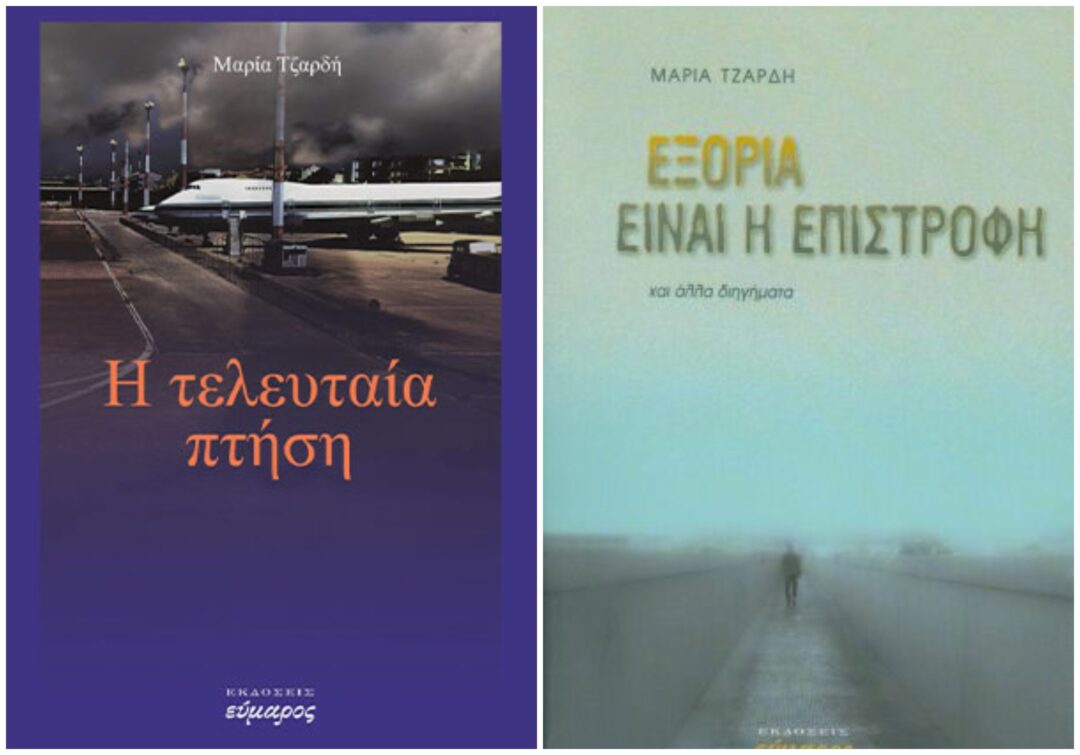

Maria Tzardi was born in Piraeus where she still lives. Ste studied at the Philosophy Department of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and at Paris Vincenne a Saint Denis. She has a post-graduate degree in Public History. She worked as a high school teacher in public education. She has published the following books: Εξορία είναι η επιστροφή [Εxile is the return] (2016), Η τελευταία πτήση [The last flight] (2018) και Οι ξένοι [The Outsiders] (2023).

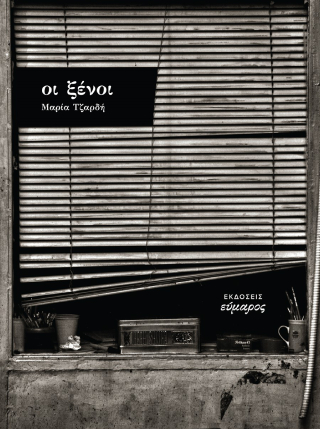

Your latest writing venture Oι ξένοι [The Outsiders] was recently published by Evmaros. Tell us a few things about the book.

The book is a collection of ten short stories about otherness. They refer to the Other, including myself as a writer, since, as it is rightly said in some of the stories, it is as if I see myself in the mirror. The heroes – paranoid, immigrants, gypsies, sick, delinquent – are alienated from society and struggle to restore their own – always fluid – identities.

The book tells the stories of refugees, immigrants, gypsies, delinquents, the sick and the dying, all those excluded from society. What is that make their stories so attractive?

I reckon that we see ourselves reflected in many of the stories. Alienation, marginalization from society as a whole but also from our own desires, uprooting also in the existential sense that makes individuals turn to something small, insignificant as long as they feel it is theirs. We have all become outsiders at some point.

How does literature converse with the world it inhabits? Where does literature meet history and society in your writings?

History and society have always been reflected in the literature of every era. Our feelings, our experiences, our opinions may stem from our psyche, but they are also formed by the environment in which we live.

I consider that I write with my gaze directed at questions of the present, at least the way myself or my heroes experience our relationship with reality; yet always with historical or social references. The fact that all three of my books move on the edge of the fantastic does not negate this relationship.

Which are the main themes your books delve into? Are there recurrent points of reference in your writings?

A recurrent theme in my books is alienation. In my first short story collection Exile is the return, the central theme referred to the words of Gunther Anders that the country to which I am returning is a country where I have never lived before.

In my novel Last Flight, I essentially unravel Giorgio Agamben’s theory of the “State of Exception”. I focused on communities of individuals literally exiled from society.

In my latest book, The outsiders, people living outside social conventions and norms try to form their identity through the gaze of Others.

Do you agree with those who argue that Greek writers have a preference for short form and that short story collections have outweighed novels and longer narratives?

Novels have more to do with more structured narratives; in the post-war era, for instance, they reflected the country’s gloomy reality.

The crisis of recent years has led to literary fragments, given that, as Dimitris Tziovas would say, “the concept of a homogeneous national culture” has been called into question.

This is perhaps the reason – certainly not the only one – for the greater production of short stories.

How do Greek writers converse with global literary trends? Where does the local/national meets the global and the universal?

As I already mentioned, we have moved away from grand national narratives and focused on “a new kind of humanism”. This has enabled contemporary Greek writers to converse with global literary trends. The local, the social, the personal now refer a universality that appeals to writers and readers all over the world.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE