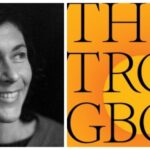

Maria Louka is a journalist and screenwriter. She has worked as screenwriter and editor-in-chief for Cosmote History, ERT, Vice, and independent documentary films. Currently she’s making a documentary on gender-based violence. As a journalist and columnist, focused on gender issues, human rights, refugee crisis and governance authoritarianism, she has contributions to various print and online media. Maria was the recipient of the ‘Eleni Vlachou’ Journalism Award in 2013, and the Migration Media Award in 2018; four times nominated for the European Press Prize, she is currently a member of its Preparatory Committee. In 2021 her first novel was published. She has also contributed in five books.

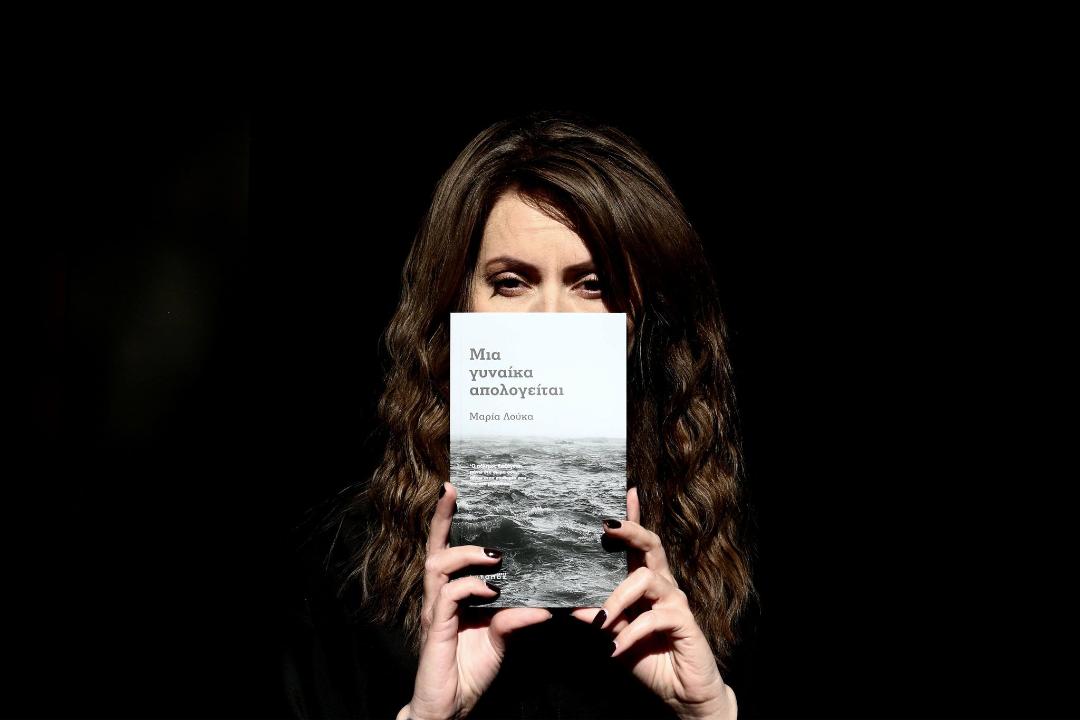

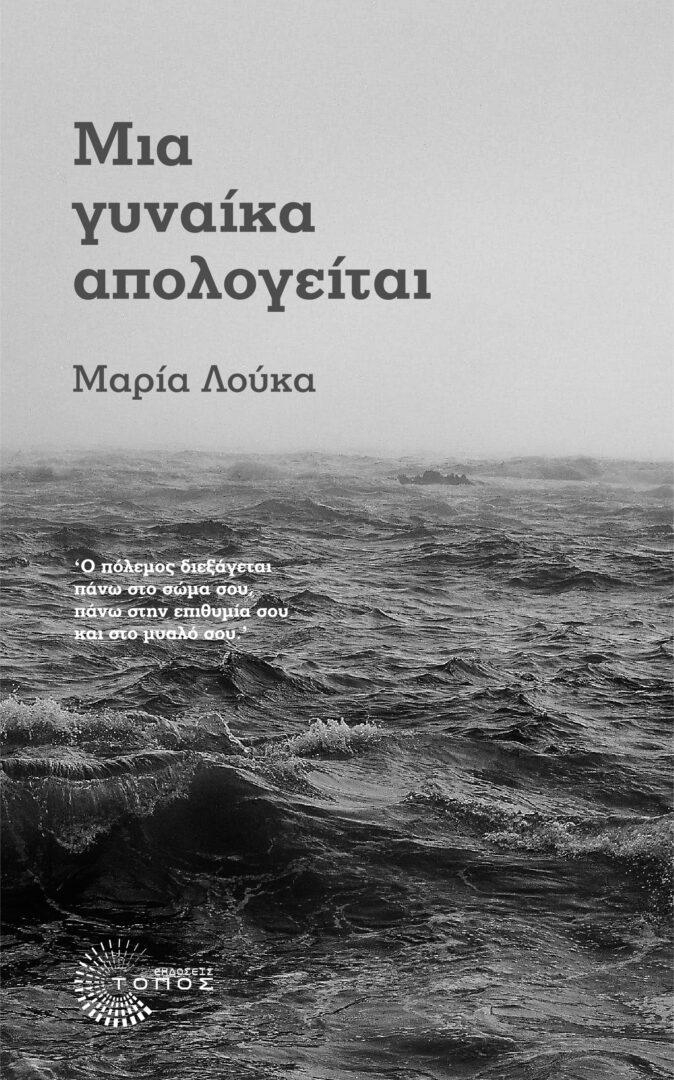

Your most recent writing venture Mια γυναίκα απολογείται [Α woman apologizes] (Τopos, 2021) is inspired by real stories of women that fell victim to gender violence. Tell us a few things about the book.

This book is a novel and my first complete attempt in literature. My starting point was the real story of a girl experiencing multiple vulnerabilities. She was abused by her father and one night, she stabbed, in self-defence, the man who sexually attacked her and her minor friend. The judicial system has unfortunately shown none of the needed sensitivity and led the girl to jail. She was released a few months ago. Her story was framed by the solidarity of several women’s and feminist organisations. This support has resulted in greatly softening the deep feeling of abandonment that this girl has been experiencing. Given this cause, extracts of collective and embodied experiences were intertwined with this girls’ story through this literary adaptation.

I made an effort in writing a story about the institutional dead-end and the societal contempt that is experienced by many survivors of sexual harassment. I am really glad that the book was met with acceptance, it got sold out on its first print, reached reading clubs, feminist collectives, libraries and prisons. It helped me experience a unique opportunity to get in touch with women from diverse social backgrounds, sharing confessional moments that were greatly moving.

Gender, in its political connotations, has been a key part of the public dialogue in the last few years. What about its revolutionary potential in literature?

Gender is the most rigid category of meaning and we are lucky to live in an era that gender discourse has characteristics of an intersection of epistemological edge and civil unrest. Discussing specifically about literature, I think we’re in this bitter yet liberating moment of realization that lots of our teenage readings, lots of the books that were established as ‘’masterpieces’’ and the very literary rule itself, are all mediated though a male lens and to a great length reproduce gendered hierarchies, stereotypes, romanticizing of gendered abuse and objectifications of women’s bodies. There have of course been heretic and groundbreaking women’s voices that disrupted the patriarchal monotony: from Virginia Wolf and Clarice Lispector, to (our local) Matsi Chatzilazarou and Margarita Karapanou. They did not enjoy the same recognition, though, and it is even sadder to realize that there might have been many others who were lost into the official register of literature’s history.

However, I think it’s the first time now that we can discuss about a clear, pluralistic and ever-growing feminist and queer literary current. Amazing, heartbreaking, enraged and sarcastic literary texts and poems are being written by women and LGBTQI+ people all across the globe (and lately Greece). Lived dream, new found words and form upheavals become popular because we can relate to them and they involve us. I personally seek these books, I enjoy them, I feel them as small apocalyptic experiences, like a pull of the curtain that can show both inside and outside of us. I feel optimistic even more by the fact that the next generations will have much more and more useful tools about understanding the world.

More generally, how does literature converse with the world it inhabits? Could literally be used to talk about key social problems? And in turn, could literature and art in general, be used to imagine what could be radically different realities?

Generally speaking, literature and art, don’t necessarily need to visualize different worlds, different ways for us to exist and relate to each other. A part of literature is dedicated to defending the present, essentially acting as a refined column of power. This part, is quite often hegemonic. I mean that conservative and emancipatory views are in battle in the field of literature. Until quite recently, the view that a creator cannot express an opinion on social issues, was left unchallenged. That is to say that even literature has to be viewed under a critical gaze. This, for example, is what the works of some exquisite new age writers are comprised of. I refer to writers like Eduard Louis and Ocean Vuong. The kind of literature that interests and fascinates me is the one that has a place in what’s at stake in society. This comes out of the lives of oppressed individuals and returns to them, it questions class/ethnic/sexual privileges. This type of literature, yes, I think it acts in an empowering way, it weaves a different reality on its own, where you can find softness, solace and oxygen to fight back against the widespread violence and the prolonged social melancholy.

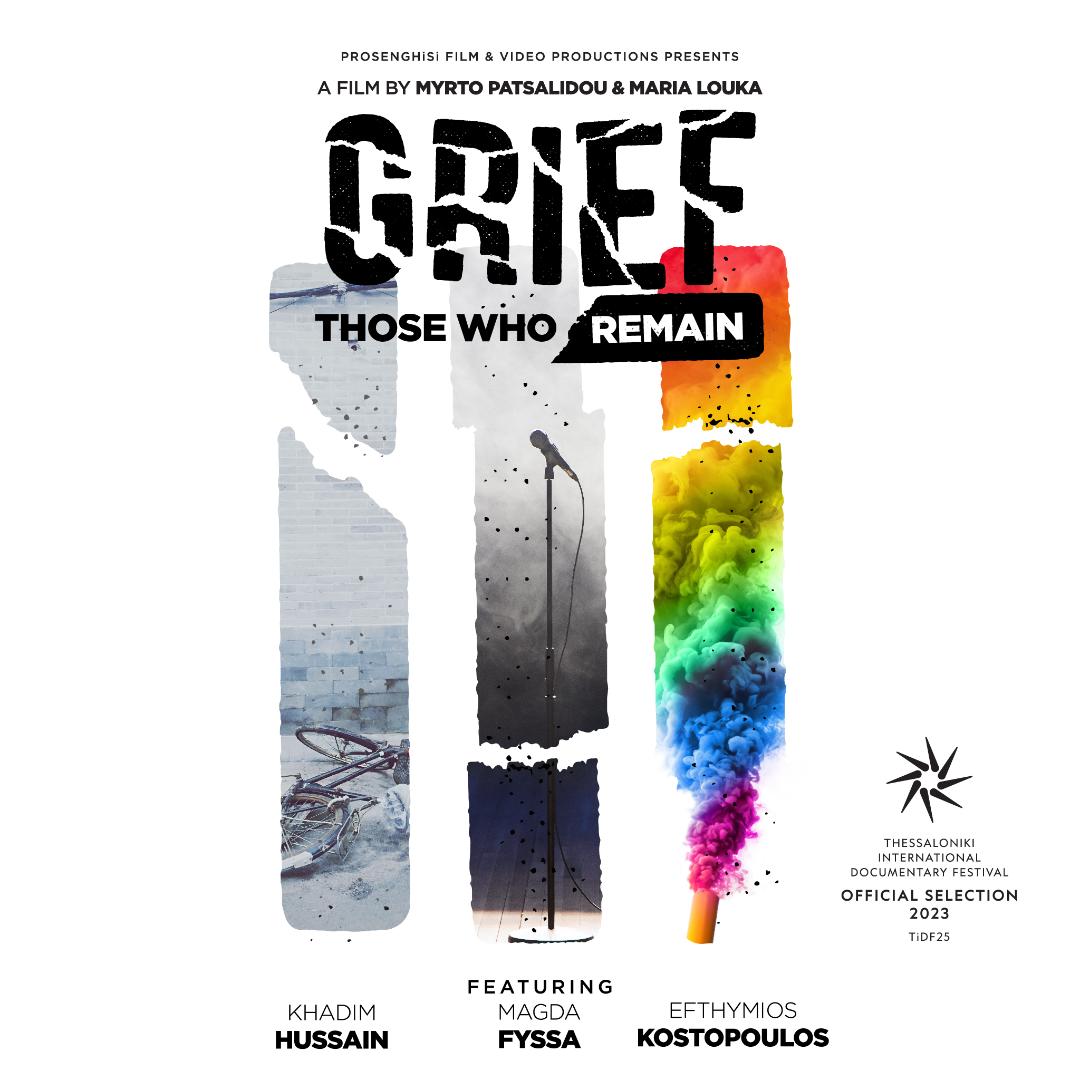

Τοgether with Myrto Partsalidou, you directed the documentary “Grief-Those Who Remain” based on three stories that shocked Greek and European society: the brutal murders of Shahzad Luqman, Pavlos Fyssas and Zak Kostopoulos. Tell us a few things about this venture of yours.

The idea about this documentary was produced a few months after the murder of Zak Kostopoulos, whom I personally knew and deeply appreciated. What was underlined by the analyses of Bauman and Baudrillard is that in modernity, mourning was moved from community to private space, which, if we think about it, is in fact quite hard. What I saw by observing these specific cases by short or longer distance, is that mourning performance had a public side as well, they would return back to community in a way of transforming pain into a claim for justice and defense of memory. Therefore, given the boundaries that are set by a documentary, I was interested in attempting to depict these psychosomatic fluctuations and the social impact that they create. Now that I see the complete movie, while it’s traveling through festivals and movie theatres, beside the trauma by fascist-racist violence, I find the love of these families for their children and I feel grateful that they trusted us. The documentary continues on its journey and I hope it can reach as much of a larger audience as possible. Unfortunately, phenomena like far right violence and fascistisation have again grown in numbers while forming a very gloomy environment. At the same time, I have started filming the second cinematic documentary about gendered violence and transition from trauma to empowerment. Script and direction are cosigned by Nina Maria Paschalidou and myself.

An award-winning journalist, cinematographer and writer. What is that binds all these different attributes together?

The truth is that the last years I gradually withdraw from journalism, maintaining only a small piece of editing and interviews. It wasn’t exactly a choice, it happened due to the deregulation of the media landscape and the divestment in research. A few years ago, due to ethical reasons, I left the Medium I worked at and found myself in unemployment. I was called by a publisher who made me an offer to work at a big website’s flow. It was of course something totally different from what I used to do, mainly feature & investigate stories. He specifically told me: “Mrs Louka, I understand you are overqualified for the specific position but I would suggest you’d think about it, because you won’t find anywhere else to pay you for what you want to do’’. He was totally right, that’s why I remember this chat so intensively.

I turned to TV and film productions. This path offered more employment opportunities but it eventually creatively evolved inside me. I found new narrative tools that helped me tell stories that I considered important to be told. I really love literature and theatrical text. However, I haven’t secured the necessary means for surviving, so I can’t really focus on what I love doing. I mostly work on that during the very limited margins of my free time. Thus, I hope I can finish my second book soon, which is about a view on my own experiences of pregnancy, motherhood and familiarity from within a literary prism.

In recent years, there has been a burgeoning of art and literature whose presence in the public sphere are quite notable. How would you comment on this strong civic awareness?

Indeed, the last years, modern civilization has been marking a course of rebirth in several fields. Lots of theatres are full of modern Greek dramaturgy, Greek movies are making a remarkable run in international festivals and of course, there is a constant publishing production with increasing influence. First of all, this indicates that antiquarianism, which governs the political, academic and artistic world, is small-minded and is getting off of its radar the modern artistic dynamics, which under incomplete or minimal institutional support are talking much more into the heart of our era. It also shows that there’s an audience that is restless and is seeking identifications, refuges, inner questions and collective reflections in art. What is happening is wonderful and it is a pity that it’s not encouraged by the State, as it should have.

How do Greek artists and writers relate to world trends? Where does the local/national interweave with the global?

I think that the new literary generation is definitely discussing with global trends in literature, it is influenced and inspired by them. The case of feminist and queer literature is such an example. What, in my opinion, is important to point out, is that this exchange is no longer only about the Western worldview that has functioned hegemonically for decades, overshadowing other cultural contexts. I notice with relief that important literary voices of my generation, influenced by post-colonial studies, place a great emphasis on Arabic and African literature. Also, of particular interest is the contemporary Balkan production, with which writers and poets in Greece are associated. I can roughly bring to mind Rumena Buzarovska’s works that have been embraced by the people living in Greece and which are very close to our own representations. In any case, the issues are international, i.e. the rise of the far right, patriarchy, class inequalities are found all over the world. From there on, obviously, in each social formation, special forms are assumed that intersect with structural contradictions and historical continuities.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE