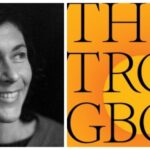

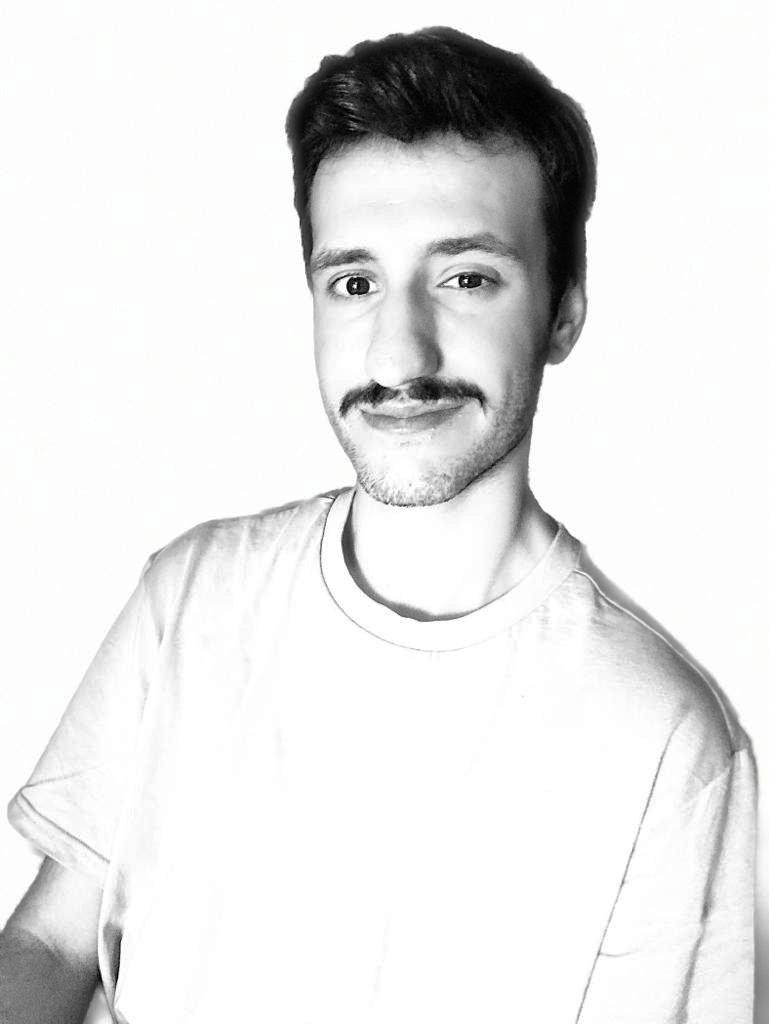

Haris Kalaitzidis was born in Athens in 1999. He holds a degree in Sociology from the University of Cambridge and a Masters in European Philosophy from Royal Holloway University. He runs the column Ιλεκτρίσιτυ in LiFO, while his theoretical and political texts can be found in various magazines and collective volumes. His first novel, Πολεμική Μηχανή (2022, HESTIA Publishers), has been included in the shortlists for awards given by the magazines Αναγνώστης and Κλεψύδρα, and was recently honored with the Μένης Κουμανταρέας award by the Hellenic Authors’ Society.

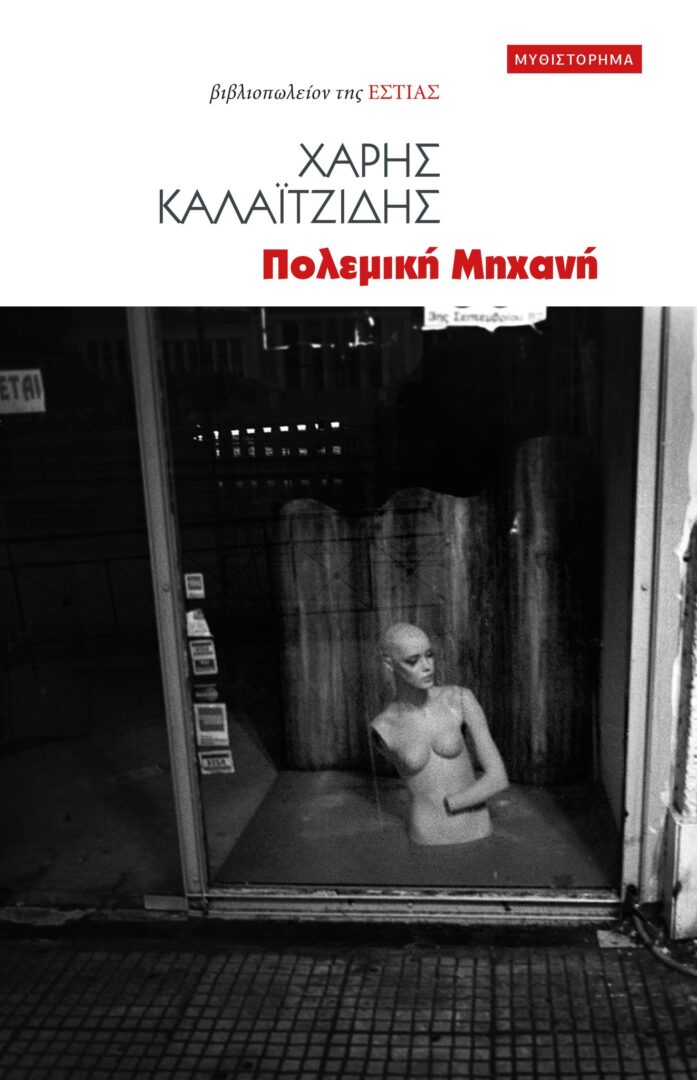

Your first writing venture Πολεμική μηχανή (Hestia, 2022) received the ‘Μenis Koumantareas’ Award of the Hellenic Authors’ Society. Tell us a few things about the book.

War Machine follows Barholomew, a Greek neo-fascist drinking himself to death. Bartholomew drinks until the moon swells up in his chest, until his desire becomes dislodged, until he escapes from his Self like vomit from a mouth. He lives two other lives: As Dionysis, he grows up in the Greek countryside, falls in love with men, clashes with his abusive father, and ends up in the army; as Ariadne, she grows up in a dark home, bounces among psychiatrists and clinics, and has an intense love life. In their lives at the margins of society, and through the institutions that wound them, both characters come in contact with Bartholomew, and, eventually, with each other.

“The book refers to the fascism of everyday life, the fascism that takes root in our bodies and our loves, the one that makes us love our chains and desire what makes us sick”. Tell us more.

The above line is an uncited paraphrase of a quote by Foucault, which encapsulates the conceptual core of my novel. Essentially, it proposes that we cannot understand fascism in its more macroscopic (historical, organized, collective) forms, without examining the vast array of structural micro-fascisms that prefigure it and produce it: Not only the family, but also school, religion, the army, and work.

At the same time, this notion asks us to examine political categories through the prism of desire and psychological investment. As the novel tries to show, fascism is not just an ideological or conceptual phenomenon, but also something that people desire, something that can take root in our personal relationships, in our everyday habits, in the way we love… In this regard, the novel is indebted to the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari (from whom it also borrows its title).

What about language? What role does language play in your writings?

Language is everything, or almost everything, I’d say. What makes each art form distinct is its unique medium. So writing is not really about telling a story (an oral tradition can do that), expressing profound thoughts and meanings (the task of philosophy and critique), or creating vivid imagery (the domain of the visual arts). Writing has to do with language, the way we inhabit it or perhaps the way we act when we finally understand that it inhabits us; the way we may experiment with it, push it to its limits, try and find what it can do, what new sensations and affections it can produce.

This is something that poets dare not forget, but that prose writers sometimes fail to understand. If I read a prose piece and the language is bland, then that piece is finished, good for nothing, dead. So the struggle is always one with language–for it, with it, and against it–burrowing inside its depths and trying to break through to what exists beyond.

How does literature converse with the world it inhabits? Could it be used to imagine what could be radically different realities?

Literature can and has played a role in imagining radically different realities. Its history is full of heterotopias, inverted orders, images of potential presents and social relations which escape unfreedom. One need not go as far as the utopias of Le Guin; Márquez’s tales of magic or the thematization of friendship in the Beats will also suffice.

Literature has also functioned as a critique of the present, a reflection of the world it inhabits in a way which highlights its failings and traps. Telling the tales of the oppressed, or finding the oppression (psychological, spiritual, or otherwise) in the lives of those not considered oppressed, are tasks which contemporary Greek literature has taken seriously.

What I’m trying to do–and what is at stake, I’d say, with the novel I’m currently writing–is situated between these two routes. It does not explore alternate realities, nor is it content with critiquing the one we find ourselves in. Rather, it investigates a radically different subject, a new voice, a novel sensibility that necessarily has a disparate relationship with the reality of the world around us. And this relationship, I have come to discover, is one of warlike joy.

Which are the main challenges new writers face nowadays in order to have their work published? What role do the social media play in the promotion of new literary voices?

The challenges one faces in order to be published are probably fewer than the challengers they face in order to be able to write. Writing takes time, and (usually, albeit not always) some level of education. So it takes quite a bit of privilege to be able to write.

Getting published is probably easier, or has become easier over the years. Once again, privilege plays a role: Many new writers choose to self-publish, paying in order to get their work out. But there are several publishers who are keen to work with new writers without asking for money, and whose criteria are generally solid. The hardest thing is not getting published, but getting people to read your work. This is where social media come in.

I have a very negative view of social media. I think they are an appetizing trap, cultivating self-destructive habits based on addiction, binding us to vicious circles of time-consuming apathy, promoting narcissism and self-centeredness, enhancing our anxiety and distress… And yet, they are absolutely necessary for a new writer (or artist, or journalist) trying to find an audience for their work. The way the publishing process is structured, the task of promoting books mainly falls on the writers themselves, and occurs through social media. In this way, these platforms remain inescapable, a kind of necessary evil. Although they have helped me promote my work, I often feel that using them amounts to a kind of self-limitation, a hindering of creativity and thought.

How do young writers converse with global literary trends? Where does the local/national meets the global and the universal?

Young writers may converse with the global by reading works from other contexts; lines of influence and alliance criss-cross countries and continents. This is, of course, something that the internet has contributed to.

But one may also discover the global simply by looking at their own experiences, and what is closest at hand. In an age of unprecedented interconnectedness, the issues we face are very similar, and fragments of personal experience are potentially generalizable.

Reading the poetry of young people from different Western countries, for instance, one finds the same issues, again and again: Cities that are transforming, problems with rent, bills and wages, a hostile environment pierced through with moments of joy. In a similar manner, one can discover common ground when reading the poetry of young women from around the globe: themes like female friendship and solidarity, as well as a broader shift in tone, a voice that speaks with the world, and not to it or beyond it.

A young woman writing poetry does not need to have read similar things in order to produce such works. By looking at her own life, her own experiences and desires, she may arrive at the same conception, discovering the universal in the local, or, better yet, constructing a “local” or “singular” universal – the only kind we have left.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE