Vassilis Kimoulis was born in Athens. He studied philology and linguistics at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. He has been working in publishing since 1990 as an editor, translator and communication consultant.

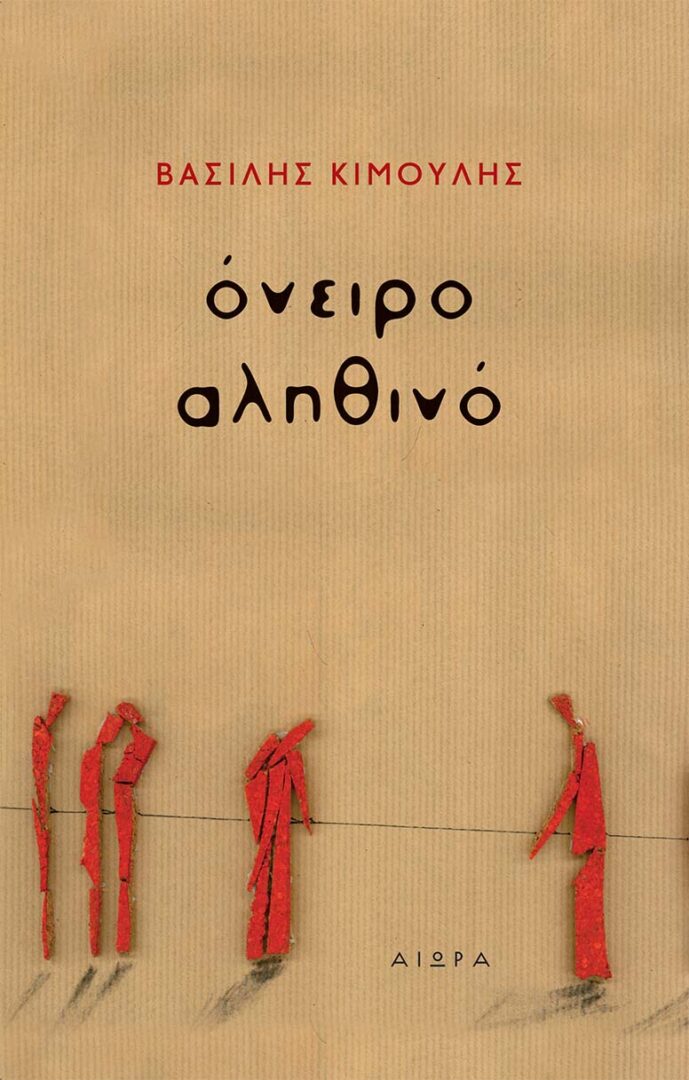

Your latest writing venture όνειρο αληθινό [True dream] has just been published by Aiora. Tell us a few things about the book.

True dream comprises 21 short stories, ranging from 1 to 31 pages, that move between fantasy and reality. Although the stories are read independently, often the same characters and events flow in and out of one another, like a musical chorus, a reminder that behind the everyday chaos there is “continuity, a hidden purpose.”

The unfolding of the stories, like slices of life, is not so much linear as circular, and deepens in each cycle. And on this journey, from the magic of childhood to the demystification of adult life, the paradox lurks and invades, to confirm the words of Haruki Murakami that “everyone just keeps on disappearing… and all that remains is a desert”.

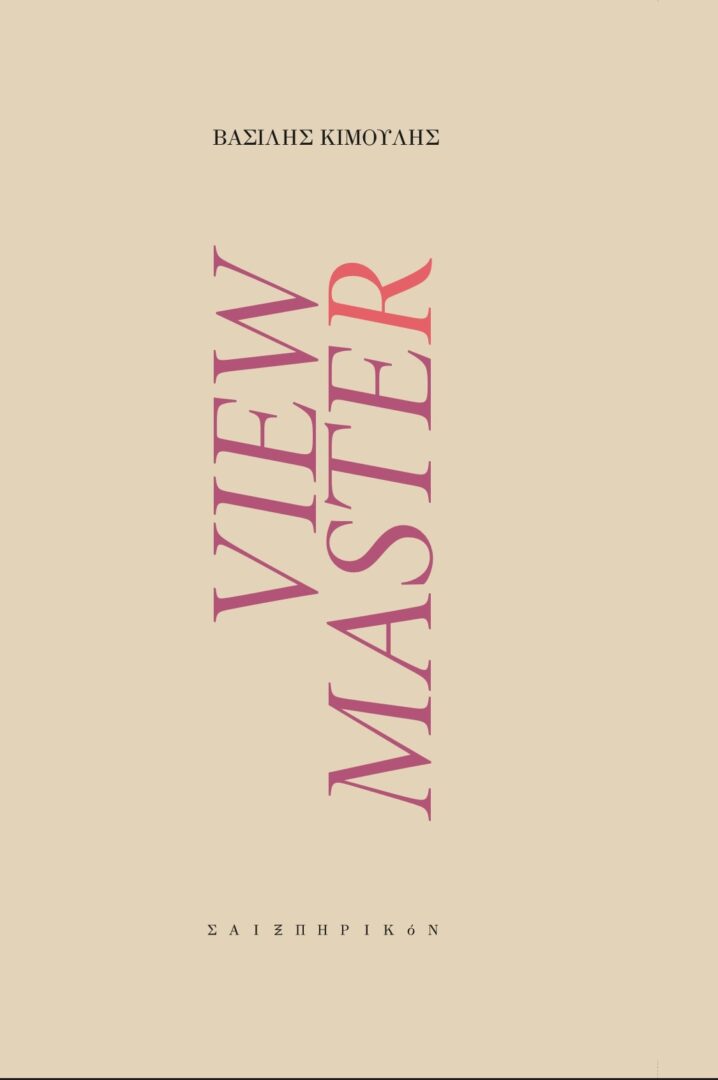

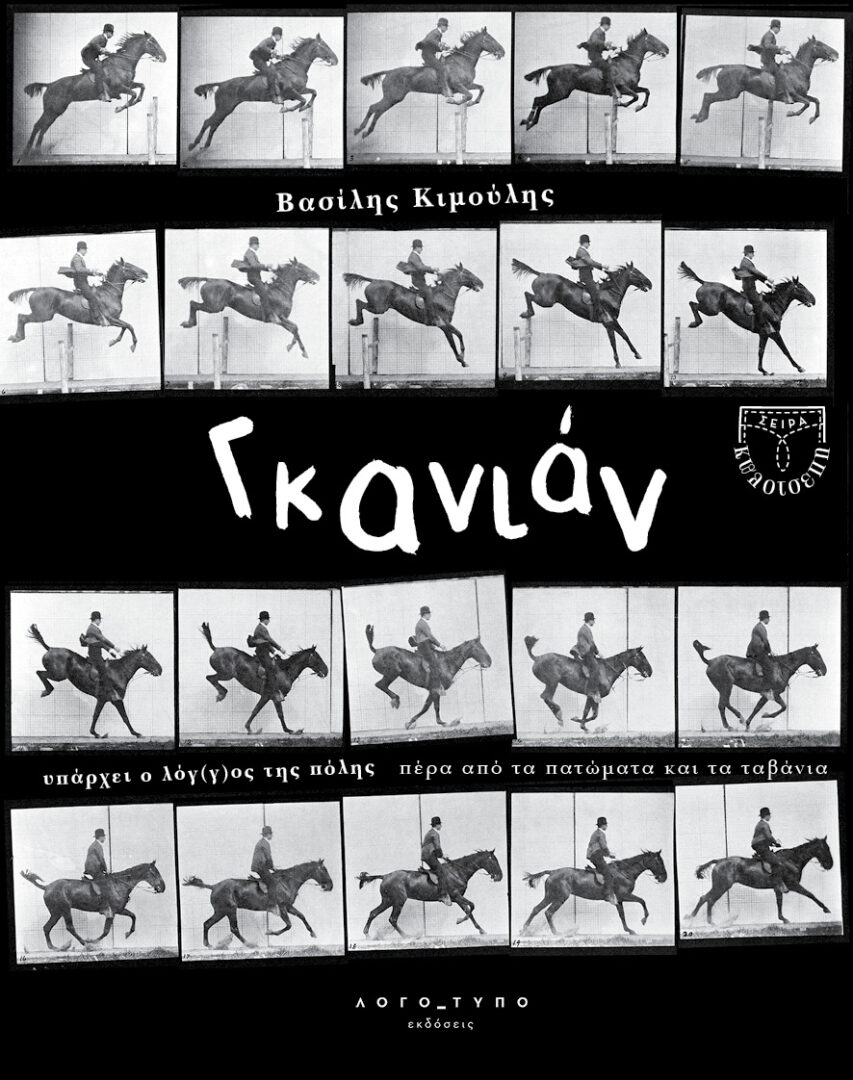

In 2023 two more books, that is a poetry collection titled View Master (Saixpirikon), and Γκανιάν [Gagnant] (Logo_typo), a hybrid of fiction, poetry, biography and essay, were published. Could you elaborate on their content? Which are the main themes both your prose and poetry touch upon?

Conversely, in order of publication, with Gagnant published first followed by View Master, the poetry collection has the same obsessions as the other two books: time, desires, denials, loss, change, creation, mixing all of the above into the mush of memory and reconstructing them like a dream or a nightmare.

The feel of View-Master (which refers back to the cult 80s toy, that looked like binoculars into which you inserted a paper disc with photos and, at the push of a button, watched a succession of 3D still images – a home ‘cinema’ before video, a controlled magic), the feeling these poems leave me with is like sunbathing, in summer, on a wonderful beach with sparkling crystal waters, with a secret worry gnawing at you from the inside.

On its part, Gagnant is a frenzied narrative in 19 plus 1 chapters, where the narrator converses in the present, or on a journey into the past, or in the world of the dead, with a colorful company of creators – poets, prose writers, playwrights, painters, songwriters, choreographers, filmmakers, traveler-writers, rock star-poets, emperors-philosophers, etc.-, mostly foreigners (except for Margarita Karapanou and Stella Haskil), mostly dead (except for Haruki Murakami) and to a large extent victims of suicide. It is the most uclassified and mischievous of the three books, definitely anti-heroic. As the narrator concludes in the last chapter, in the Ode Gagnant, “gagnant is the non-gagnant.”

Ηow does literature converse with the world it inhabits? Could it be used to imagine what could be radically different realities?

Literature sheds light on realities that already exist within us. We carry inside us the science fiction, thriller or romance, which we will read tomorrow in some sort of written form. And if our writing sometimes becomes surreal, it is because surrealism is the new realism – as long as you stand still amid the daily flow of the city and observe what is happening, how you co-exist with the other. Our realities constitute the fuel of literature. And at the same time, our reality is also enriched by and through literature.

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this respect, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie? Can translation ever be unethical?

Translators have a great responsibility since they are the ones who give voice, in their language, to the foreign creator. I agree with those who argue that moving from one language – and thought and culture – to another is a kind of ‘betrayal’; how to transfer the original meaning intact to a new linguistic environment, how to transmute into your own reality that foreign element that words carry within them. The act of writing itself is also a form of betrayal; the passage from that primary vision (if not a vision, then a shiver or suspicion of feeling) from the infinite possibilities that exist to the finite marks on paper.

In an interview to Reading Greece, Elena Pallantza emphasized on the “artistic dimension of a translator’s work”, who “seeks to literarily address the problem of silence of a text in a foreign language”. Would you agree that translation is an autonomous act with its own artistic and aesthetic value?

In translation you cut the original text into pieces, to transform it into something completely different (visually, aurally, linguistically, grammatically, syntactically), in the hope that you create a new work, in your own language, remaining essentially faithful to its original intention, that is to evoke an equivalent emotional vibration. If you succeed, it gives you immeasurable pleasure – a joy that is somewhat sadistic, since you had to take the work to pieces, like an assembled toy, to make it yours.

I agree that translation is an autonomous act with its own artistic and aesthetic value; yet the main difference is that the way has been paved by the creator. You, as a translator, are called to recognize the signs and not get lost on the way, so that you can, returning to your place, convey to others what you saw, what you heard and what you felt on this dictated journey.

How does Greek literature converse with global literary trends? Where does the local meet the national and the universal?

In the era of globalization and homogenization, where the great capitals of the world, from Athens and Madrid to Mexico City and Tokyo, converge in the image of a vast hotel, and beyond the programmatic banality of the fact that we are all human, the local has become alarmingly universal, and vice versa, and literature cannot remain unaffected.

New movements, experimental ways of writing, still unsorted, hot global issues, from the systematic destruction of the planet, the fake wealth marked by indicators, the normalization of the televised retread of bombings and violent expatriations, to movements for human rights, self-determination, etc. overwhelm the whole planet, shaping the new “existential” landscape, both local and global, perhaps even more global as it is more radically local. And the diversity in perspectives, experiences and their expression through of speech, is what creates this enormous wealth of narratives.

At its core, however, I reckon that narration, both locally and globally, has always been the same: “Once upon a time there was someone who…”

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE