Directed by Spiros Jacovides, Black Stone is a movie focusing on Greek society with extraordinary sensitivity. Masterfully using the form of pseudo-documentary, Jacovides comes up with a story that encapsulates defining aspects of Greek realities.

Striking a balance between comedy and drama, Black Stone dives into Greek reality, exploring its complex and dysfunctional aspects in an insightful manner. Humor and hope are among the key elements of the movie aimed to capture the dominant role of family in an ever-changing Greek society.

Based on an imaginative script, solid characters, and excellent performances, the movie has participated in more than 30 film festivals in Greece and around the world, 63rd Thessaloniki Film Festival, 34th Trieste Film Festival, 39th Alexandria Mediterranean Countries Film Festival, 17th Los Angeles Greek Film Festival, 8th Berlin Greek Film Festival and New York Film Expo to name a few. To date, it has won 23 awards, more than 10 of which are audience awards.

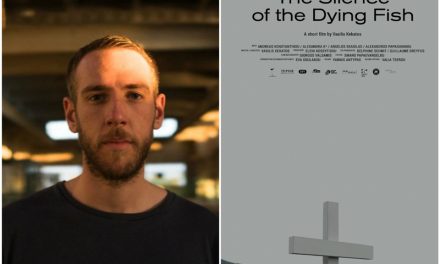

Spiros Jacovides was born in London and studied Directing at the London College of Printing and the Stavrakos School. In 1998 he was a guest student at the Berlin Film Academy (DFFB). He lives and works in Athens writing and directing commercials, documentaries and video clips. He has written and directed three short films. Black Stone is his first feature film.

The director spoke to Greek News Agenda* about the creative process of his award-winning film, his meticulously crafted characters brought to life by compelling performances from the film’s cast, as well as the future of Greek cinema.

Black Stone focuses on the pathologies of Greek society. How did you manage to raise such important issues in a humorous way? Would you consider yourself an optimist?

There was a great deal of risk and many traps along the way. We wanted to tell a tragic story with tragic heroes combining drama and humor. I believe that it is possible to talk about the most tragic things in a humorous way without them losing their importance. Humor makes them even more accessible to the viewer, humor makes life more accessible in general.

The challenge was to balance drama and humor. I think we did well in this respect. Another great challenge was to adjust our story to Greek society and to touch upon different themes of Greek reality while focusing on the story and its characters.

The problem is that the Greek reality is so complex, so dense and so rich that you don’t really know where to start. At the same time, the Greek audience is familiar with it, so you have to be very careful in order to portray it in a convincing way.

Generally speaking, I am an optimistic person. This is the reason why I picked a hopeful ending for this very tragic story. I believe in good, in hope. I believe that there is no evil without good no matter what happens in our lives.

How would you define Black Stone in terms of genre?

I would define it as a tragicomic mockumentary or pseudo-documentary since it gives you the impression of realism and verisimilitude. The viewer knows that he is not watching an actual documentary. Nevertheless, he is drawn to the story and he subtly accepts the illusion that he is watching a true story.

The protagonists are talking directly to the camera, which essentially means directly to the viewer. This genre also gives the director a great deal of freedom of movement while focusing on the actors’ performances.

The Greek mother figure is dominant in Black Stone. Do you think that modern Greek women relate to this kind of relationship of codependency and oppression? Do you think that Greek society is conservative when it comes to family?

The Greek mother was the main reason for me to tell this story. Her footprint is huge in Greek society. She has managed to survive in an extremely patriarchal and conservative society, living through others; her children, her husband, her parents; never fulfilling her own desires, needs, dreams and ambitions.

She is a woman who never discovers her true identity. In fact, she never takes her life in her own hands. I am mostly referring to the women of previous generations. Fortunately, things are gradually changing, slowly but in a solid way. Nowadays, a woman can be a mother and, at the same time, in search of her own identity. However, the influence of previous generations persists and still haunts us to a great extent. The pathologies continue to be passed on from one generation to the next but society is changing and the world keeps moving forward. Conditions today are very different, there is hope.

The character portrayed so delightfully by rapper Negros tou Moria (Kevin Zans Ansong) is a figure we see for the first time in Greek cinema. A child of immigrants, born in Greece, Michalis feels that he is still not being equally accepted. Do you think that these stereotypes have changed in Greece? I was thinking about how crucial the role of the arts is in enhancing the visibility of individuals or groups that society simply chooses to ignore.

The character of Michalis played by Negros tou Moria is indeed a character that we don’t often see in Greek cinema perhaps because he belongs to a new generation, he is a new addition to Greek society and societies need some time to adapt and accept new facts.

I believe that Greeks are deeply xenophobic but not racist whatsoever. They do not historically carry the ideology of racism as Americans, English, Austrians, etc. However, they are historically insecure concerning external factors and phobic. They hang on to what they have acquired so far. As a result, they are afraid of the “unknown” and feel threatened by it.

Although both of these conditions, xenophobia and racism, may ultimately lead to the same negative outcome, I think it is important to make this distinction because I believe that it is easier to overcome a strong phobia than to change a deeply rooted mindset.

I absolutely agree with you about the crucial role that the arts, and especially cinema, can play, not only in terms of visibility, which is very important, but also in terms of empathy, i.e. being able through films to enter into the microcosms of the characters and the tragic situations they experience and to emotionally perceive the big problems in their complexity and not to stay on the surface which unfortunately leads to oversimplification and apathy.

The casting of the movie was brilliant. How did these collaborations come about?

For me, casting is one of the important and favorite parts. I work very much with my instincts in the final selection of actors.

I may choose an actor even if I know nothing about his work just by seeing some photos of him or after having coffee with him. Over the years, I’ve learned to trust my instincts. I think an important part of directing is learning to listen and trust your instincts. I also pay attention to every single role, big or small, even the extras because in a film you are making a world, a whole universe so everything is equally important, from the biggest element to the smallest detail.

The characters of the film were in my mind right from the beginning. I worked very hard on the script but also during the editing process. The characters never stopped evolving and that’s one of the magic parts of the process of a film; the continuous, unstoppable and unpredictable creative process.

From shooting to editing, the film took 10 months to complete but the total process took seven whole years! Making a feature film in Greece can be hard and unfortunately, few make it to the end. There is always a high degree of uncertainty and the process is sometimes in vain. It takes tremendous faith, perseverance and patience and that is why I have great admiration and compassion for all my colleagues.

One of the reasons so many related to your film certainly has to do that characters are so recognizable and authentic. Does the new generation of Greek filmmakers focus on Greek society? Do you think that contemporary Greek cinema has the place it deserves in Greece and abroad?

Yes, I believe a new generation is focusing on modern Greek society, reality, and soul, especially on the Greek family. For decades, I think many of us felt that many films were made that we could not relate to. This changed with Giannaris, Tsitos, Economides, and Lanthimos. These films focused on new themes the Greek audience could relate to but also managed to go beyond the borders and excel abroad, thus finally achieving an outward-looking orientation in Greek cinema.

Personally, I will never forget the day I saw Yannis Economides’ Spirtokouto. For me, it was a revolution, as if an era died and a new one was born. It gave me tremendous strength and energy for the future.

*Interview by Dora Trogadi

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Filming Greece | Asimina Proedrou on her film “Behind the Haystacks”