Artemis Leontis is Professor of Modern Greek and Coordinator of the Modern Greek Program at the University of Michigan, USA. Her academic interests involve comparative literature, classical reception studies, theories of modernism and modernity, encounters of modernism and Hellenism, Greek America and Diaspora studies and travel writing.

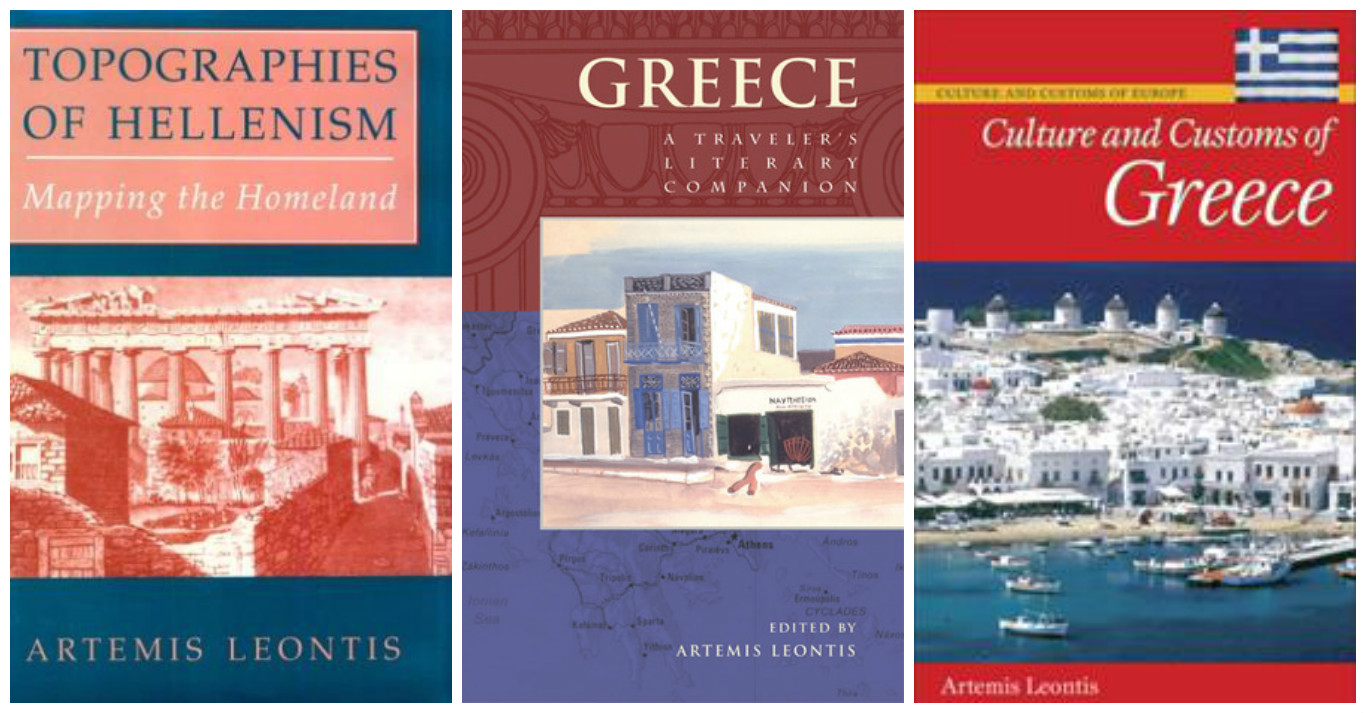

Professor Leontis is Arts & Humanities editor in the Journal of Modern Greek Studies, “the only scholarly periodical to focus exclusively on modern Greece.” Her publications include Topographies of Hellenism: Mapping the Homeland (1995), Greece: A Traveler’s Literary Companion (ed. 1997), and Culture and Customs of Greece (2009). She is currently working on a book-length cultural biography of Eva Palmer Sikelianos, an influential American notable for her promotion of Classical Greek culture, weaving, theater, choral dance and music.

Artemis Leontis spoke with Rethinking Greece* about American students’ response to Modern Greek studies and the international debate on the euro crisis and Greece, Americans’ perception of Ancient Greece, Greece’s “territory” discursive remapping by scholars and writers, Hellenism and Eva Palmer Sikelianos’ life and impact as ethical-aesthetic self formation, as well as the historical conjuncture of the words “Greek” and “crisis” and the “category of the Greek” as source of inspiration, intervention, and institution.

How does the international debate on the euro crisis and Greece affect Modern Greek Studies and its appeal to students? How do undergraduate students respond?

Creating and sustaining Modern Greek Programs in institutions of higher learning in the United States has been ongoing work for me since the early 1980s when I began teaching Modern Greek to undergraduates and helped build language and culture programs first at the Ohio State University and then at the University of Michigan. In these thirty some years, circumstances in US higher education – from our student’s demographic profile to the cost of education to graduation requirements and job prospects – in addition to developments in Europe and Greece affect the appeal of Modern Greek Studies.

Today’s students’ childhood memories are filled with collapsing structures (the Twin Towers, pretext of the Iraq War in 2003, Lehman Brothers, US economy, Arab Spring, the Occupy movement, and the unifying principles of the European project); they have a particularly developed sense that they are living in a precarious world. I find them to be among the most media savvy and skeptical students I have ever taught. Greece of today is on their radar. A few students never move beyond the stereotype of the lazy Greek or dangerous immigrant from the Middle East. Most, however, who are endlessly suspicious of political and discursive representation, don’t accept what they see.

We capture the attention of this body of students by helping them develop skills that contribute to their global literacy. By literacy I mean a historical understanding of the global interconnectedness of systems, circumstances, and relationships. To teach Greek language and culture is to help students make historical sense of the international web of communications surrounding Greece, its politics and economic future. Contemporary sources also draw them in, including international articles, blogs, and political cartoons, graffiti and street art, weirdwave films, poetry, and other Greek writing of the 2000s.

How do undergraduate students in the US respond to the international debate on the euro crisis and Greece? They want to focus on the most recent news, to post and comment rather than to dig deep to discover the long history of complex relationships. The never-ending back and forth of Europe and Greece plays on certain discomforts. They can’t decide which of the two is the collapsing structure. At the same time, they are fascinated by contemporary sources and events that show how people in Greece are struggling to retain their humanity in a world that seems to grow darker by the day. At their most creative, they find their own ways to assemble, post, curate, review, tweet, emojify, and generally care about what is happening in a place quite distant from them.Ancient Greece has been central to American ideals, especially during the 19th century. To what extent do these ideals inform Americans’ perception of Modern Greece and its place in Europe?

Ancient Greece is a muted point of reference in the US. It is ubiquitously present in high art and popular culture, architectural elements and myth-studded products. Yet it does not register deeply, since most Americans don’t receive the classical learning that was part of their great-grandparents’ public education. I just saw a wonderful movie, Captain Fantastic, in which a father takes his family of six kids off the grid to the mountainous wilderness of the state of Washington, in order to educate them, body and soul, to become philosopher kings after the utopian model of Plato’s Republic. I saw it with a group of well-educated filmgoers. We took time to talk after we saw the film. We discussed its many aspects, and everyone caught the Platonic reference; yet most did not have the classical learning to work through the alignments of the film and the Greek text. Another example: the campus of the University of Michigan, where I work, is very much in dialogue with ancient Greece in its structures, decorative features, collections, and founding principles. Next year the University is celebrating its bicentennial, and those Greek elements have been collated on a website; yet for most people they function as a sign of learning and prestige without actual content.

Nevertheless, Ancient Greek sources have been a crucial point of reference used by journalists and cartoonists to make sense of news about Greece since 2010. Much of the reporting and cartoons have traded on literary or visual puns on the classical repertoire. The reporting has been good for comedy but detrimental to both a nuanced understanding of Greece’s position and the prestige of classical sources, as Lauren E. Talalay argued in her article, “Greek Antiquity, The Economic Crisis, and Political Cartoons” in the Journal of Modern Greek Studies.

A related question is what Americans prefer to see when they visit Greece, which they are doing in rather large numbers these days. I cannot speak for all Americans, since the country is large, diverse, and divided. Regarding just the small group of young people who traveled with me recently to Greece, I observed that they were eager to visit classical sites but preferred to see them from an unusual angle: from behind the scenes, for example, or down below in juxtaposition with daily life. They wanted to experience the din of present life: to lose themselves in the moment and catch a glimpse of how people live from day to day. (Most people in Greece put on a good face for tourists these days, and the students wished they comprehended Greek better so they could understand the nuances of what people said.) Americans are more interested in solidarity networks, support groups, humanitarian efforts, relief sites, hot spots, etc., than in the classical legacy. One archaeologist colleague recently said that if he were to organize a study tour on the archaeology of the Acropolis, he might have four people sign up, whereas a course on the archaeology of refugee detention centers would attract five times that number. In Greece in its relationship to Europe, these young Americans see the country that first experienced the world’s twenty-first century growing pains.

You have studied literature and geography as they intersect in portraits of Greece as a “contested territory” by international and local scholars and writers, but also policy makers, who try to reconcile an imaginary Hellas with a modern country. What is the relevance of such an approach to the contemporary discourse on Greece?

You have studied literature and geography as they intersect in portraits of Greece as a “contested territory” by international and local scholars and writers, but also policy makers, who try to reconcile an imaginary Hellas with a modern country. What is the relevance of such an approach to the contemporary discourse on Greece?

Territory is a conceptual tool introduced by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari in the 1980s. It is a multi-layered idea connecting world-historical processes that codify the earth. The layers of territory include 1. the physicality of the earth; 2. geopolitical interventions that mark the land and sea with boundaries and create borders and systems of their protection; 3. bodies that move about the earth and dwell on it, creating relationships of interdependence; 4. discourses and rituals (verbal and pictorial) engaged in the topographic enterprise. I am referring to not just administrative but also creative work that codifies territories; 5. and lines of flight: people, capital, ideas that flee from this codification (deterritorialization). This last layer is crucial to territory. According to Deleuze and Guattari, there is no territory without deterritorialization.

My book Topographies of Hellenism: Mapping the Homeland (Cornell UP, 1995) I studied Greece as a territory in this multi-layered sense. I analyzed interactions of literary writing with the sites of the Greek mainland and archipelago, particularly the Aegean, and with its subjects in the wake of the Asia Minor disaster. That great territorial disturbance not only initiated the flow of refugees in two directions across the Aegean; it also undermined the Great Idea, a cartographic enterprise deploying writers, politicians, and armies to map Hellenism over a much larger land mass. In the wake of the disaster, an important movement of modernist writers who came of age in the interwar period, the generation of the thirties, found ways to reconcile Hellenism with the map of contemporary Greece and to align language, ethnicity, archaeology, and history with geography. Their mid-century topographical rewriting of Hellenism was incredibly long-lived and effective. Traces of it keep reemerging in the present day.

My writing of that book coincided with the collapse of the Soviet Union, when the map of the world was again greatly altered. Tremendous changes in Greece followed the sequence of events that opened the country’s borders with Eastern Europe, brought in over 1 million labor immigrants, precipitated Greece’s contest with its northern neighbor over the right to the name of Macedonia, and led to the signing of treaties that changed the territorial scope of Europe and its system of association. These territorial disturbances beginning in 1989 were arguably greater than those in 1922. Especially the movement of so many people to Greece, not only highlighted the processes of deterritorialization and reterritorialization that had given Hellenism its twentieth-century contours; it also introduced competing national narratives to the story of the continuity of Hellenism.

And now we come to the present moment, with its multiplying lines of flight. I can’t think of a time when territory and deterritorialization -in the multilayered formation I have been discussing- has been more relevant for understanding what is going on: the flow of capital and unemployed laborers out of Greece; the inward flow of hundreds of thousands of refugees into Greece following the path of refugees of the Ottoman Empire in 1922; the European Union’s efforts to close its borders without ruining the European project; the return of refugees to Turkey; the Brexit vote; and creative efforts to participate through poetry and art in the writing of new territories or overwriting of old ones.

Particularly the flight to Greece of refugees and immigrants and their entrapment brings into view the layered anatomy of territory and the stakes involved in its remaking.

In your forthcoming book, you argue that Eva Palmer Sikelianos was the most influential western visitor to Greece after Lord Byron. What is Palmer’s impact and why you consider it so important?

In your forthcoming book, you argue that Eva Palmer Sikelianos was the most influential western visitor to Greece after Lord Byron. What is Palmer’s impact and why you consider it so important?

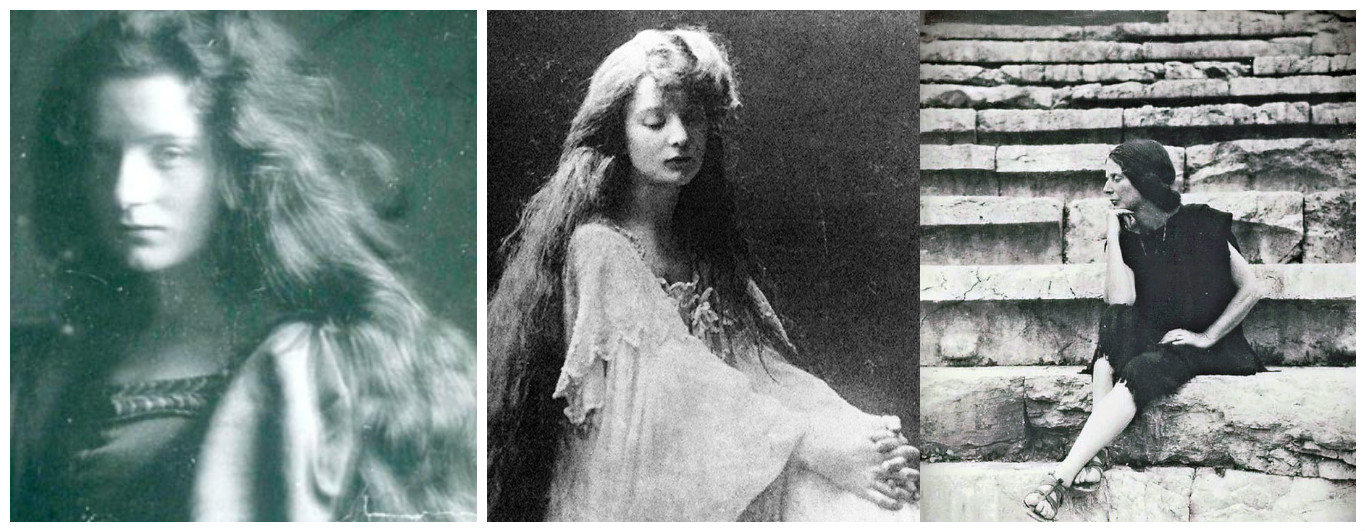

The impact of Eva Palmer Sikelianos (1874–1952), a transnational figure who lived between American and Greece is threefold: in the traces of the Delphic Festivals of 1927 and 1930; the effects of her advocacy for an anti-imperialist American political agenda in the 1940s; and in the way she made Greek ideas the subject of her art of self for her entire adult life.

Eva Palmer is not an easy figure to access. People know little about her, even though she rubbed shoulders with powerful elites in her day, in both her native US and Greece, her adopted homeland for 27 years from 1907 to 1934. Her work has been hidden behind that of more famous artists – Isadora Duncan and Angelos Sikelianos, for example. Many people still assume that Angelos Sikelianos directed the Delphic Festivals, yet she was the artistic director. Once this is known, the pieces of the festivals come together. Some elements anticipate the generations of the 1930s’ mapping of Hellenism: Delphi, an archaeological site in Greece was made to stand metonymically for all of Hellenism by organically bringing together ancient, byzantine, vernacular, and modern features. But other elements do not fit that pattern: the historical reenactments in particular, in which temporal asynchronicity prevails over topographic synthesis, and archaeological reconstructions escape the excavation site to enter modern life. Eva Palmer, who abandoned western fashions and adopted home-woven dress in search of lost ancient processes, was herself an untimely figure. Her formula for the production of the Delphic Festivals had a complex genealogy, combining the interwar effort to recollect the Greek national tradition with American women’s college Greek (?), the arts and crafts movement, turn of the century lesbian theatricals, and women’s work in the margins of archaeology. The most visible impact of Palmer-Sikelianos life’s work is this expatriate American fusion of folklore, archaeology, and the physical environment of rural Greece that became emblematic of the Greek tourist industry, as Pantelis Michelakis has observed. It is found in tourist shops that sell Greek handicrafts; the annual summer Hellenic Festival with major events in ancient open air theatres such as Epidaurus; ancient revivals in vernacular Modern Greek that showcase large-scale choruses singing and dancing to the non-western modes and rhythms of Greek music; and urban elites who have made Greek tradition the signature of a lifestyle.

The most visible impact of Palmer-Sikelianos life’s work is this expatriate American fusion of folklore, archaeology, and the physical environment of rural Greece that became emblematic of the Greek tourist industry, as Pantelis Michelakis has observed. It is found in tourist shops that sell Greek handicrafts; the annual summer Hellenic Festival with major events in ancient open air theatres such as Epidaurus; ancient revivals in vernacular Modern Greek that showcase large-scale choruses singing and dancing to the non-western modes and rhythms of Greek music; and urban elites who have made Greek tradition the signature of a lifestyle.

There is a lesser-known, transnational American side of her legacy. From 1944 to 1949, she took a very public stand protesting American foreign policy in Greece. She wrote thousands of letters to politicians, public officials, and newspaper editors. She was blacklisted by the House Un-American Activities Committee and was denied a visa when she was invited to direct part of the “Return to Greece” Marshall plan campaign in 1950. Her activism brought her into correspondence with hundreds of Americans and Greeks, and she became a node connecting a range of important transnational projects, from the articulation of an anti-imperialist American political voice; to the creation of a left-wing Greek-American lobbying force (she became president of the Greek American Council); to the effort to translate, publish, and promote Modern Greek literature in the US; to the development of cultural tourism in Greece.

For me, her most significant contribution lies in the way she made Greek ideas the subject of her art of life. She especially tried to develop techniques resisting social mechanisms of control. She did not sit still intellectually or artistically but kept changing media and refining her positions. She moved from tableaux, photographs, and theatricals representing the Sapphic life in Paris, to weaving and Byzantine music and Delphic Festivals in Greece to productions of drama and dance in the US, to writing Upward Panic. Even as she changed media and reckoned with her failures and impoverishment, Greece stayed on her horizon, giving her ever-new ways to imagine a different kind of life in opposition to contemporary consumer culture. Her life is the most long-term, sustained critique of modernity based on the reception of the Greeks that I know. Perhaps it’s time to begin thinking about the impact of the latter project.

You have said that “today the word ‘crisis’ goes hand in hand with ‘Greek’ in public perceptions” Are there some new ways in which we can “rethink” Greece now?

You have said that “today the word ‘crisis’ goes hand in hand with ‘Greek’ in public perceptions” Are there some new ways in which we can “rethink” Greece now?

The historical conjuncture of the words “Greek” and “crisis” in the media event, “the Greek debt crisis,” feeds on a broader tendency to think of the Modern Greek as the sign of a protracted transhistorical crisis, which was prompted by the institution of the Greek state on the site of ancient ruins. For non-historical reasons, that event has been codified as a mistake, a critical turning point that produced the Modern Greek, a mongrel who could be neither Greek nor modern.

For as long as I have been talking to Greeks about Greece, I have been hearing accounts of what went wrong with Greece and why the Modern Greek is an aberration. The explanations are the same, even though the circumstances that trigger the conversation keep changing. I marvel at the persistence of this trope of the Modern Greek who endlessly betrays his inner self. (Both the speaker and subject of the story are almost inevitably male.)

I wish to resist the tendency and to profess a turn to rethink Greece in the present moment of crisis. I consider this to be the byproduct of 18th and 19th century European preoccupation with ancient Greece as the model society that arose out of nowhere and vanished in a flash. I wish to push against the notion that Greece of any particular moment stands at the critical turning point, the moment of crisis when we must discern what went wrong and determine how to turn things right.

In my book-length projects, I see Greece as a territory of earth, bodies, discursive interventions, and lines of flight that sometimes cause shattering disturbances. It is continuously undergoing revision. I have studied two instances, one collective and the other individual, of Greece’s remapping. Topographies of Hellenism draws attention to the collective process by which the topos of Hellas was rewritten in a discursive mapping, through a contestation of the limits and meaning of territorial markers of Greece over several tumultuous decades in 1900s. Eva Palmer Sikelianos: A Life in Ruins, my forthcoming book, studies an individual’s ethical-aesthetic self formation in dialogue with the Greeks through the same tumultuous period. For more than half a century, under radically changing circumstances, Eva Palmer kept returning to Greek sources to make herself other: to strive to surpass herself.

Both my subjects sought after missing truths. They tried to remake Greece. What they participated in, however, was not the production of a lasting truth but an ongoing revision.

The category of the Greek is not closed but admits opposition. It is in perpetual flux, and it continues to inspire creative acts of invention, intervention, and institution.

*Interview by Nikolas Nenedakis

Videocast – Artemis Leontis, The Alternative Archaeologies of Eva Palmer Sikelianos (2014):