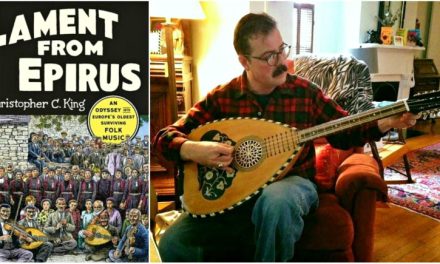

Panos Iliopoulos is a composer and performer, specializing in both early and modern keyboards. His extensive studies include musicology at the Music Studies Department of the National University of Athens, composition and piano at the State University of Music and Performing Arts in Mannheim, as well as harpsichord and historical keyboard instruments at the Conservatorium van Amsterdam.

As a composer, arranger, improviser and performer on early keyboards Iliopoulos has participated in numerous concerts, festivals and opera productions across Europe, e.g. at the Oude Muziek Festival Utrecht, Concertgebouw and Muziekgebouw Amsterdam, Markgräfliches Opernhaus Bayreuth, Theater an der Wien, Athens and Epidaurus Festival, collaborating with orchestras and ensembles such as the Geneva Camerata, Nieuwe Philharmonie Utrecht, Armonia Atenea and the State Symphony Orchestras of Athens and Thessaloniki.

He has been featured in recordings and broadcasts of TV and radio stations across Europe, as well as the record labels Etcetera, Passacaille and Puzzlemusik. Iliopoulos has also composed original music for theater productions, including “Apocalypse” at Onassis Stegi, “Casa Nova” at the National Theater of Greece and “The Holiday Trilogy” at the National Theater of Northern Greece.

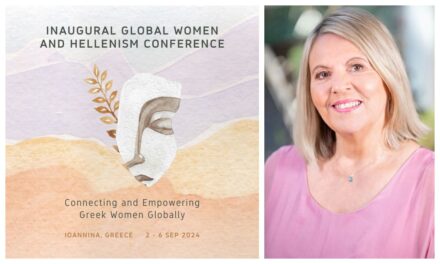

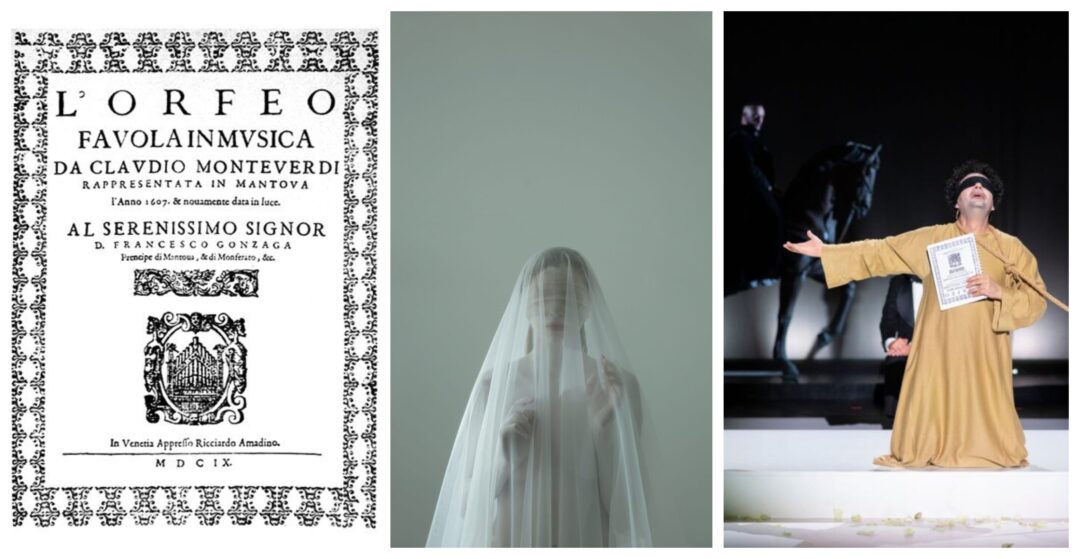

We caught up* with Panos Iliopoulos while he was in Cologne―playing harpsichord, organ and regal for the ongoing production of Monteverdi’s Coronation of Poppea―and we discussed the tentative link between early and contemporary music, the perils and promises of fusing different musical traditions, why opera is not an elitist art form and why it holds great potential for further development in Greece, and of course his latest projects, among which is “J.S. Bach – The Apocalypse,” a new opera commissioned by the Netherlands Bach Society, currently touring in the Netherlands and Germany.

The opera “J.S Bach – The Apocalypse” was inspired by the hypothesis “what if Bach composed an opera.” You were tasked with forging the opera into a unity, using music by Bach, as well as composing your own. Can you tell us more about this project? What were the biggest challenges you faced in creating the score for “the opera that Bach never wrote”?

I have to admit that at first I was somewhat reluctant and apprehensive about the project, being fully aware that it is impossible for me to write music exactly the way Bach did ―as far as not only the style itself is concerned, but also of course the unsurpassable quality and beauty of Bach’s music. So I decided to take that as a given, and approach the process with utter respect and cautiousness, by generally keeping Bach’s music as intact as possible and merely providing new music with the purpose of “gluing” Bach’s pieces together into a through-composed opera, attempting to make it as hard as possible for the listener to distinguish which bits were newly composed. Whether I succeeded in that or not, it’s of course up to the audience to decide ―but I do hope that there are moments where this indeed works.

Only on very special dramaturgical moments (for example, when the mad prophet Jan Matthijs is speaking in tongues, quoting random fragments of the John’s Revelation, or when someone is depicted describing visions they saw in the sky) did I allow myself to venture into a musical language that strays away from Bach’s ―but even then, I did employ some motivic material taken from Bach, albeit used in a completely different manner.

Some of your own projects (e.g. Broke Konsort), as well as other projects you have participated in, propose a dialogue between Baroque music and Eastern Mediterranean music (Rembetika songs, Ottoman music). What are the connections between those styles of music and what can be gleaned from the encounter of these two worlds?

Let me start by noting that, in all such attempts of fusing or juxtaposing different cultural traditions, there is always the danger of approaching them at a surface level. I am well aware of that danger, and thus I keep a very critical stance towards such attempts ―first and foremost my own!

I think that the key is to approach disparate traditions with a sense of respect, which is always what I try to do when initiating or participating in such projects. I also try, as much as possible, to not fall into the trap of cultural appropriation ―as in, to not merely “borrow” elements of a musical tradition just because I fancy them, but to also strive to have a somewhat deeper understanding of them.

This is aided by the fact that I mostly venture into cross-over projects that are referencing musical traditions in which I feel that I myself am more or less a part of, be it Greek traditional songs (with which I am acquainted since my childhood) or baroque music (with which I might have a more “constructed” ―but not less true― relationship, since I immersed myself into it later in life). That being said, there are elements of some of these traditions that allow for a more smooth and playful dialogue between them, the most important of which, in my opinion, is the improvisatory aspect. In any case, as you can imagine, I’m not striving for any sort of “purism”, and I believe that this dialogue can bring to life interesting new perspectives which can help keep these traditions alive.

As a musican who is a perfomer/improviser as well as a composer, you play ―and write for― early and modern keyboards, including harpsichord, jazz piano and electronics. What led you to explore the link between early and modern music? How does one get from the harpsichord to electronics?

There isn’t necessarily a direct link between all of these ―they’re all simply areas of interest for me. It’s not that one thing leads to another in a linear way. Importantly though, the fine line that one could say joins these areas, is that they all allow a great degree of creativity.

For example, baroque music has, by its very nature, a lot of improvisatory elements ―notably the practice of basso continuo, which I specialize in and was driven to, specifically because of the freedom it gives to the performing musician. Now, although we try to study the sources in order to get more informed about the way music used to be played in baroque times, we will never be sure; and this provides a great window for creativity and for injecting personal flair to the way one approaches the performance.

Similarly, when composing, the scope for creativity can indeed be boundless. In any event, although as mentioned there isn’t necessarily an obvious link between early music and contemporary composition, in many phases of my artistic endeavour these fields of interest have indeed come together, for instance in the pieces that I have composed for historical instruments ―sometimes even combined with the use of live electronics.

Some might argue that opera today is an elitist art form, catering to a niche audience. Do you think that opera could, or even should, try to appeal to wider ―and maybe younger― publics?

It’s not entirely accurate that opera is an elitist art form ―neither historically, nor currently. In many phases of the history of opera, it was an extremely popular spectacle ―otherwise it wouldn’t be presented in theaters that sit upwards of 1000-2000 people. There is of course the example of French baroque operas, which, while generally commissioned by the king and premiered at the palace, soon after the premiere they were performed in large theatres for the wider public. And, in our times, let’s not forget that the ticket pricing in most opera houses is quite “democratic”: if one ignores the very expensive tickets for the few, one can often find tickets which cost much less than the average, say, pop concert. So, while there might be an elitist aspect to the genre, I think that it’s surely not a defining feature of it.

My feeling is that a major issue of today’s opera is the fixation of most opera companies worldwide to the “canon”, i.e. a corpus of a few dozen operas which keep being performed again and again ―something that by the way didn’t happen at the time that these operas were actually written. Of course, if an opera was a success back then, it would be played repeatedly, but the public kept asking for new ones. Hence, something that might help nowadays in attracting a younger audience could be the commission and production of more new operas, because both the music and the subject matter of new operas will by definition be both more modern and more relevant to today’s public.

This could also help alleviate some of the aspects of older operas that pose challenges to modern audiences, such as for instance their often very long durations ―in our days, where the attention span is barely 30 or 60 seconds on a TikTok video, durations such as three or four hours seem unfathomable. Of course we have to note that these durations also served a purpose back then: people didn’t have easy access to music (no radio, no CDs, no Spotify), so they really appreciated getting a bang for their buck on the few occasions per year that they could go to the opera [laughs].

In any case, specifically in Greece there is a huge margin for improvement as far as the engagement of a broader audience for opera and music theatre is concerned, since we have a tremendous tradition in theatre ―let’s not forget that indeed opera was invented in the early baroque times as an effort to revive ancient Greek drama. Apart from that, there is very big wiggle room to experiment with new forms, beyond the “stereotypical” boundaries of opera as a genre.

Any upcoming projects you would like to tell us about?

On May 21st I will be returning to the Zamus Early Music Festival in Cologne along with my esteemed colleague Jonathan Keren in an interactive improvisation performance titled “The Oneirocritics,” where we will musically interpret, on the harpsichord and the violin, dream descriptions from the concertgoers , which will be randomly pulled out of a hat during the concert.

On May 31st, at the Alternative Stage of the Greek National Opera in Athens, there will be the premiere of “ΣUΠΕR,” a music theater performance which is the culmination of the Co-OPERAtive educational program, an intercultural youth opera hub for a mixed group of Athenians and unaccompanied asylum-seeking teens.

I had the honour and joy to work as composer for the project, and together with the educational and creative teams, we aimed to collaboratively craft theatrical stories on stage, integrating dialogue, music, singing, and visual depictions of brief narratives sourced from the teenage participants’ written works, jointly creating a music theatre piece.

Finally, a highlight of the tour of the “J.S Bach – The Apocalypse” opera mentioned above, is that it will be performed on 10th and 11th June 2024 as part of the Bachfest in Leipzig, the city where J. S. Bach lived and served as cantor for the better part of his later life.

Read also from Greek News Agenda

*Interview to: Ioulia Livaditi