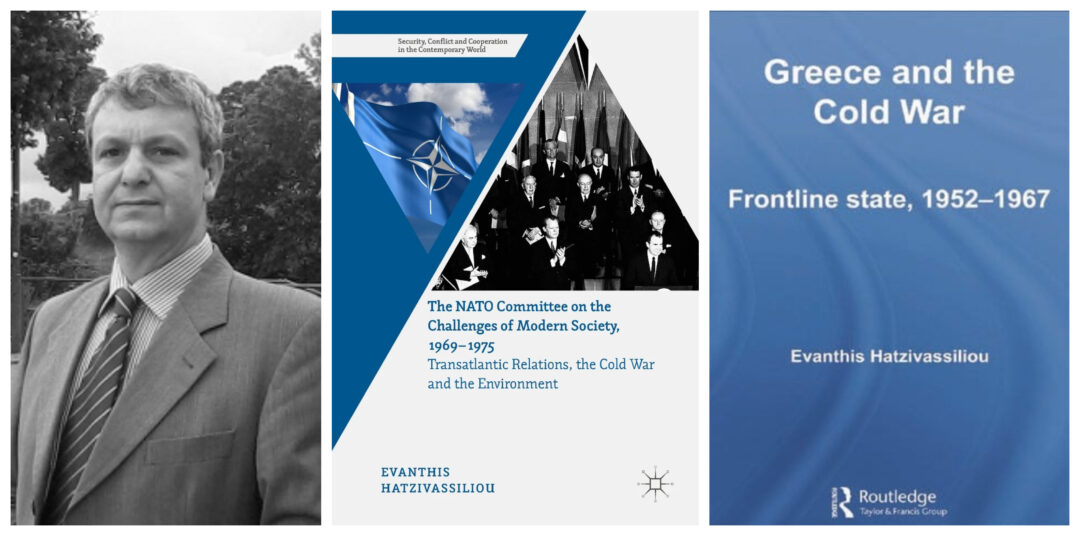

Evanthis Hatzivassiliou is Professor of Postwar History at the Department of History of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens as well as secretary-general of the Hellenic Parliament Foundation for Parliamentarism and Democracy. His research interests include international history, the history of NATO during the Cold War, Greek foreign policy and political history and the Cyprus Question. Among his more publications are ‘The NATO Committee on the Challenges of Modern Society, 1969-1975: Transatlantic Relations, the Cold War and the Environment’ (2017), ‘NATO and Western Perceptions of the Soviet Bloc: Alliance Analysis and Reporting, 1951-1969’ (2014), and ‘Greece and the Cold War: Frontline State, 1952-1967’ (2006). Professor Hatzivassiliou is also Fellow of the Eleftherios Venizelos Foundation and a member of the Greek-Turkish forum, a one-and-a-half-track diplomacy initiative, founded in late 1997 with the aim to promote dialogue and communication between Greece and Turkey.

On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne* Evanthis Hatzivassiliou spoke with our sister publication GrèceHebdo** on the importance of the Treaty for Greece and Turkey – as well as for the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East, on the new international legitimacy established by the Treaty, on the mandatory exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey, and finally, on Eleftherios Venizelos, the great political man who was the head of the Greek delegation during the Treaty negotiations.

It is generally believed that the Treaty of Lausanne only concerns Greece and Turkey, while in reality it is a treaty signed by eight countries. Could you briefly explain to us the importance of this treaty for both countries as well as for the wider geographical region?

The Treaty of Lausanne marks the solution of the Eastern Question, one of the most important, long-lasting and persistent international problems of modernity. The Eastern Question involved the possible dissolution and succession of the Ottoman Empire, and the control of the Straits; therefore, the whole region that was then called the “Near East”. The question raged at least since the last quarter of the eighteenth century, and touched upon the ambitions of the peoples of the region for political representation as well as upon the geopolitical priorities of the great powers and the long struggle between Britain and Russia for controlling the access to the Black Sea (therefore, also Russia’s access to warm seas).

In 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne led to the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the Turkish Republic; to the creation of the successor states in the region that we now call “the Middle East” (even if some of them were for a time mandates of Britain and France, such as Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, the region of Palestine, Jordan); and to the definite settlement of the international borders in the south-eastern area of the Balkans between Greece and Turkey. Moreover, many other issues were settled, such as the Ottoman public debt, international navigation in the Straits, or issues regarding minorities; among the latter was the harsh compulsory exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey. Thus, as the solution of the Eastern Question, the Treaty of Lausanne regulates international relations in the wider area of the Balkans, the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East. For this reason it also forms the basis of Greek foreign policy since then.

In your announcement at the recent ELIAMEP Conference for the 100 years of the Lausanne Treaty, you mentioned that the Treaty is a pillar of a new international legitimacy, as for the first time, small and sovereign states participated equally in it. Would you like to elaborate on this aspect, given that the issue of multilateralism remains relevant in international relations today?

The new international order that was created following the First World War was a profoundly liberal one. It involved the dissolution of the empires in East-Central Europe, and the definite rise of the nation-state as the main system of governance in the continent. At the same time, the creation of many new nation-states was also combined with an equally necessary move towards multilateralism, thanks to the setting up of the League of Nations, the brainchild of the US President, Woodrow Wilson. In the League all members of the international community participated, small states and great powers, on the basis of sovereign equality. This was a profound change compared to the past, when the existence and rights of small states were often ignored: during the nineteenth century, the European Concert had been a procedure of great powers only. Inotherwords, theinternationalsystemnowbecamemoreparticipatory. This was a decisive change in the international community. This new liberal legality was challenged cruelly by the forces of revisionism, especially Nazi Germany, but was confirmed with the outcome of the Second World War.

The Treaty of Lausanne, even with the admittedly dark aspect of the Greek-Turkish compulsory exchange of populations (a result of the crushing Turkish victory over Greece in 1922), brought to this part of the world the new international legitimacy, while it also settled international borders in the region, an element of decisive importance for the new order. As such, the Treaty of Lausanne is not only a crucial regional arrangement, but also the pillar of the wider international order in this part of the world.

In recent years, an opinion has been expressed – albeit very limited – that the Treaty of Lausanne ceases to be valid 100 years after its signature. Could you tell us what is the validity of the Treaty today and what is its importance for the future, especially of Greek-Turkish relations?

An international Treaty does not “expire” because of an anniversary. The Treaty of Lausanne continues to be in full force, and from the point of view of Public International Law it could not be otherwise. Apart from this, according to the prevalent view in International Law, the territorial settlement that such a Treaty establishes, would still remain in force even if the Treaty itself, as a legal instrument, were ever invalidated (which anyway is an extremely unlikely eventuality). Thus, the Treaty of Lausanne forms the basis of Greek-Turkish relations for the past 100 years and for the future. For this reason, the two countries need to show great care in respecting and implementing the Treaty: without this, chaos could ensue both in bilateral relations and in the wider region.

The mandatory exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey was a painful chapter in the Treaty of Lausanne, with significant socio-economic and political ramifications for Greece, while it was considered by many to violate human rights. How would you characterize the exchange of populations and in what way, in your opinion, did it determine the course and identity of modern Greece?

The Greek-Turkish compulsory exchange of populations was not only a controversial but a shameful act. This was because the compulsory character of the exchange fully violated human rights by depriving individuals of the right to choose. This was why it was even claimed, at that time, that the Exchange Convention was invalid according to International Law. This, on the other hand, was a rather theoretical view, since the exchange had already been done.

The compulsory exchange was imposed by the victorious Turkey on the defeated Greece of 1922: even since the autumn of 1922 (namely, before the signature of the Exchange Convention in late January 1923), the Greek populations had already been violently expelled from Western Asia Minor and from Eastern Thrace, while Turkey solemnly declared its determination to expel the remaining Greeks from Pontus, Cappadocia and other areas. In other words, even before the conclusion of the Exchange Convention, the larger part of the expulsion of the Greeks from Turkey was already a fait accompli, and could not be undone. The compulsory exchange was a fundamentally Turkish choice, which defeated Greece could not question. It was not the preference of Athens. The Greek perceptions, plans and aims regarding the populations had been expressed at the Treaty of Sèvres, which left populations in their homes, in the context of much more liberal arrangements.

At any rate, however inhuman and controversial from a legal or moral point of view, the reality that the Exchange Convention imposed shaped the contemporary Greek state and nation: the vast majority of the Greeks were now concentrated within the borders of the state; Greece became a “conservative” power, a supporter of the status quo. The exchange was a hugely traumatic experience. However, the Greek people and the state managed to overcome the trauma, and create a contemporary European state, capable of economic and social development.

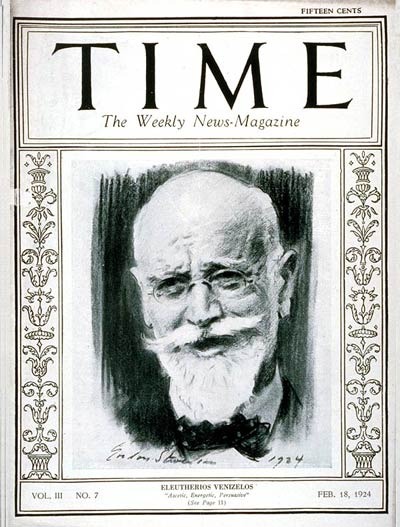

Eleftherios Venizelos was appointed head of the Greek delegation to the negotiations in Lausanne, although he no longer participated in the country’s governance. Do you think that the personality of the Greek politician, who was indeed the visionary of the Great Idea, contributed to upgrading of Greece’s position during the negotiations of the Treaty of Lausanne? What was his contribution to maintaining peace in the region?

It is worth noting the tragic element in the case of Eleftherios Venizelos’ presence and roles during the Lausanne Conference: he was called to deal with the devastating consequences of a crushing defeat which could be attributed, to a large extent, to his own electoral defeat of November 1920. He had lost power, then the country had lost the war, and he now had to deal with the disaster. Yet he accepted this enormous responsibility.

There is little doubt that the international prestige of Venizelos was always greater than that of his small country – more so, of the vanquished Greece of 1922. This became very clear during the Lausanne Conference. Thus, even representing a defeated country, Venizelos managed to reach an honourable peace. Moreover, Venizelos’ sincere acceptance of the territorial status quo was decisive in Greece’s decision to abandon the Megali Idea and become a status quo power. This greatly aided the evolution of Greek policy, and shaped the international roles of the country for the past 100 years, as a pillar of stability and normalcy in the wider region, and as an ardent supporter of international legitimacy and of the liberal international order.

* The Treaty of Lausanne, the most enduring of the post-World War I peace accords, is a historic treaty signed on July 24, 1923, establishing national borders in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East, with the aim of restoring peace in the region after the disastrous First World War. The treaty was signed by the Republic of Turkey, which had succeeded the defeated Ottoman Empire, on the one hand, and by the Allied and Associated Powers (France, United Kingdom, Italy, Japan, Greece, Serbia and Romania) , on the other hand. One of the most radical elements of the Treaty of Lausanne, particularly from a humanitarian point of view, is the obligatory exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey.

** Interview granted to Ioulia Elmatzoglou | GreeceHebdo.gr

Read also from Greek News Agenda:

- 100 Years since the Treaty of Lausanne: Looking Back, Looking Ahead

- Davide Rodogno: Multilateralism plus prevention is a way of imagining a better future in humanitarian interventions

- Emilia Salvanou on the Greek-Turkish population exchange after 1922 and the making of Greek refugees’ memory

I.L.

TAGS: FOREIGN AFFAIRS | GREECE-TURKEY RELATIONS | INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS | MODERN GREEK HISTORY