One of the milestones of 20th century Greek national narrative is the Asia Minor Catastrophe, i.e. the defeat of the Greek Army in the Greek-Turkish war (1919-1922) and the resulting wave of refugees of Greeks from Asia Minor to the Greek state. Literary representations of life in Asia Minor and of the refugee experience played a crucial role in that. Indeed, a significant number of widely-read and influential novels and short stories concerned with Asia Minor and the Asia Minor Catastrophe have appeared since 1922. Some of these texts are central to the canon of modern Greek literature.

The book

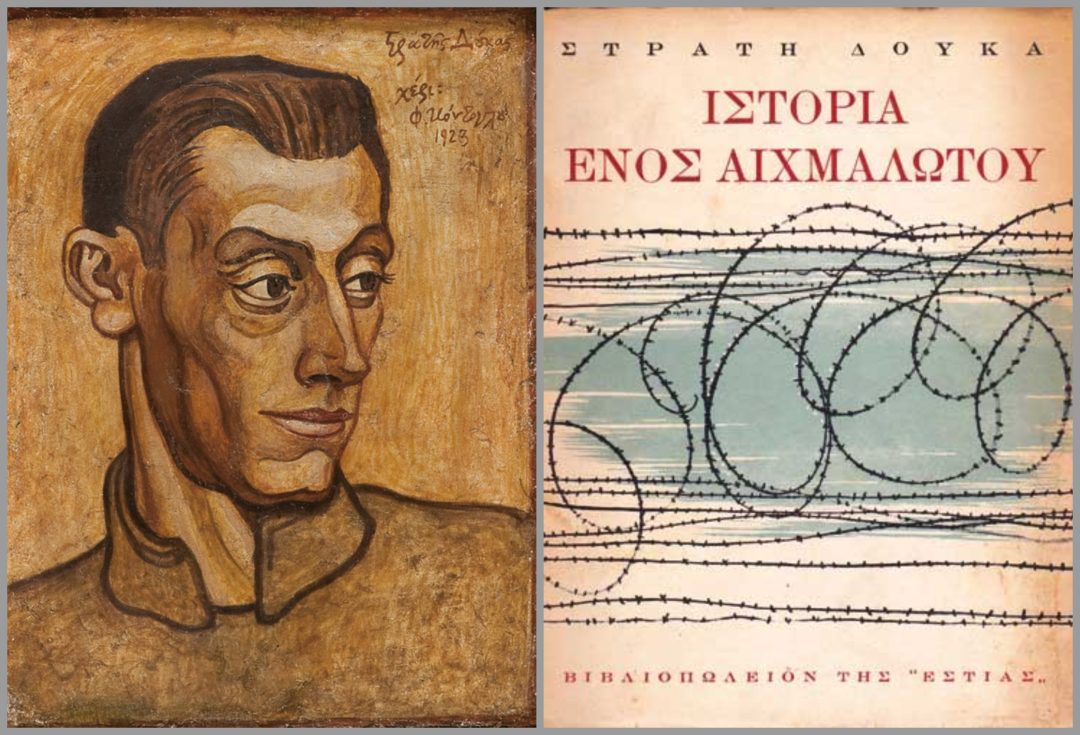

Stratis Doukas’s A Prisoner of War’s Story (Greek title: Iστορία ενός αιχμαλώτου) – first printed in 1929 – is one of the most powerful literary accounts of the ordeal of those Greeks who were unable to escape in time across the Aegean to mainland Greece after the Asia Minor Catastrophe in 1922.

The narrative is based on the true story of Nikolas Kozakoglou, who is captured by the Turkish Army after the disaster and made to march for days with little food or water. On the march the Turkish soldiers mistreat the prisoners, strip them of all valuables, and leave the stragglers to the mercy of vengeful civilians. Eventually the prisoners are separated and given to local villages as slave labor. Kozakoglou and a companion escape, returning to their home village only to find it pillaged and destroyed. Disguising themselves as Turks in order to survive, they part company in search of work. After much wandering, Kozakoglou finds work as a shepherd and, claiming to be a Kosovar, he develops a close relationship with his kindly employer, who, surprisingly, is treated sympathetically in the narrative.

Living in constant fear of discovery, he manages to learn enough of Muslim ways to continue his charade through a series of narrow escapes until he finally saves the money he needs to leave. With the aid of his unwitting employer he secures travel papers and makes his way to Smyrna, where he manages to board a steamer bound for Constantinople. When the ship makes a stop at Mytilini he persuades the Greek officials that despite his convincing Turkish appearances he is really an Anatolian Greek, whereupon he is allowed to stay in Greece.

With asthmatic rhythm and the trepidation of the fleeting, the protagonist recounts the hardships, misfortunes and humiliations suffered, in a work that is sparse in language, but shocking for the events it reports and for the many others that implies. At the same time, the dispassionate portrayal of bare events removes the story from its wider historical context, rather emphasizing the epic struggle for an individual’s survival. It is a testimony to sheer human versatility and resilience and indirectly reveals how, although Greeks and Turks lived together on the whole peacefully in earlier times, they also remained deeply ignorant and suspicious of each other’s religious practices.

A book that stands in direct dialog with literary textbooks and testimonies of the time (e.g. Ilias Venezis’s Number 31328), it can be seen as an episode of a larger epic, blurring the distinction between fact and fiction, legend and history. Carrying within it the a longing for repatriation, as a longing for peace, for the eradication of war instincts, for the brotherhood of peoples, it constitutes an important European example of 20th century anti-war literature.

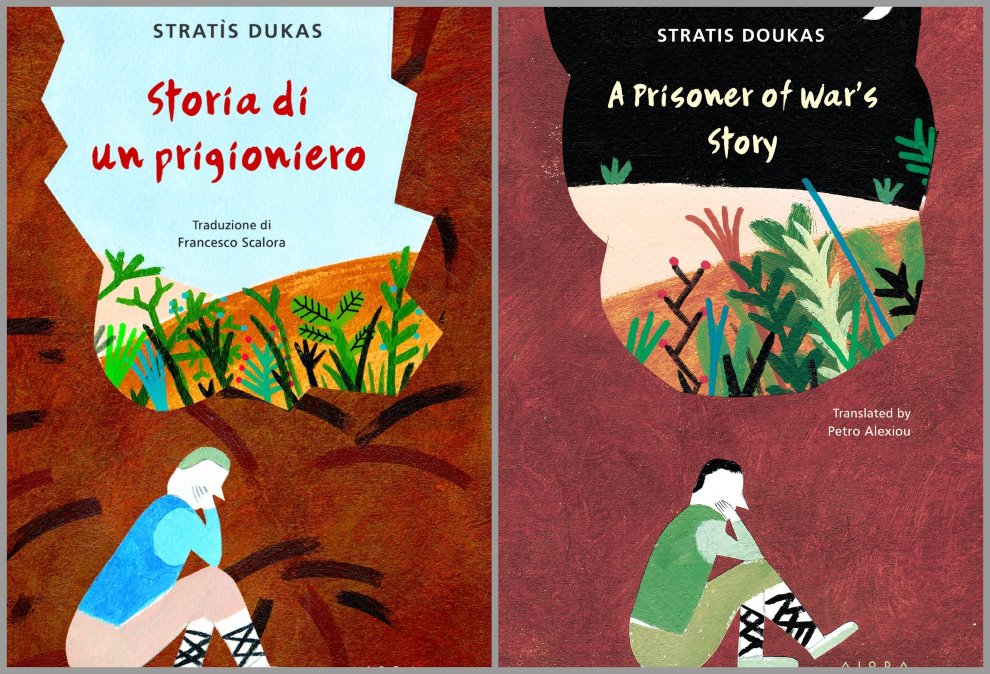

An Italian Translation of the Book is Now Available

The book was recently translated in Italian by scholar Francesco Scalora (Aiora Books, 2022) under the title Storia di un prigioniero. On this occasion, Francesco Scalora spoke to Reading Greece about the importance of the book, which comes to fill an important gap regarding the familiarization of the Italian reader with a crucial chapter of Greek history.“The translation work undertaken by Italian Μοdern Greek scholars, thanks to which the promotion of Greek literature in Italy has been facilitated in the last seventy years, is indispensable. It’s due to their efforts that the most well-known Greek literary works have been and continue to be published, offering Italian readers the opportunity to enjoy Greek literary creation and culture. However, there was an important chapter of Greek history that greatly influenced Greek literature, which was missing among the works translated to date (both in poetry and in prose). That is the Asia Minor Catastrophe and the displacement of Greek communities that followed, which cast its heavy shadow on all subsequent literary production”.

“The centenary of the Asia Minor Catastrophe was for the Italian reader a great opportunity to be introduced through literature to a Greek historical event that is not so well-known abroad. Thus, in 2022, a number of related works such as Number 31328 by Ilias Venezis, Farewell Anatolia by Dido Sotiriou and A Prisoner of War’s Story by Stratis Doukas were published in translation. A Prisoner of War’s Story is definitely one of the most emblematic works of Greek prose. The years in which Doukas writes, as Mario Vitti emphasizes, are years in which some Greek writers, motivated by new ferments, promoted an intellectual renewal, reflected in the literary field by the adoption of innovative narrative methods, thus announcing the most contemporary work of the so-called Generation of the 1930s”.

As for the challenges he was faced with while translating the book, Scalora comments, “Achieving the right balance between a flat, simple narrative and the need to depict the seriousness of the painful historical events, Doukas conveys the message of the brutality of war through a testimony of personal survival, without resorting to excessive narrative and artistic embellishments that aim to emphasize the dramatic dimension of a historical event that is already tragic in itself. The result is a text that stands out for its expressive simplicity, for its folk-like spoken word. A text with an evocatively lyrical style, where the narrative-testimony, recorded as a historical document, and the author’s literary art, come together, giving life to a text that, overcoming social, political and even more ideological-national reasons, becomes a universal message of humanity. The translator’s duty lies in not betraying the message Doukas tried to convey, and in order to do so, he has to respect the expressive simplicity of the text”.

The author

Stratis Doukas was born in 1895 on Moschonisi island, off the Asia Minor coast, and settled in Greece as a refugee after the Greek–Turkish war (1919–22). He served as a soldier in the Greek army in the First world war and in the ill-fated Asia Minor campaign. Together with his university friend Photis Kontoglou and with Stratis Myrivilis, he co-founded the Mytilene Club of Musical Arts. He conducted journalistic research that was published in numerous newspapers, and started writing literature in 1929, to later also take up painting.

A Prisoner of War’s Story, published in 1929, established his reputation as an innovative writer of a new unadorned first-person narrative style. His writing encompasses lyrical prose, arts journalism and studies of important figures in the visual arts, including a nearly biography of the sculptor Υannoulis Chalepas. Doukas died in Athens in 1983.

A.R.

Read also: Reading Greece: The Asia Minor Catastrophe in Modern Greek Literature; BOOK OF THE MONTH: “Land of Aeolia” by Ilias Venezis

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE