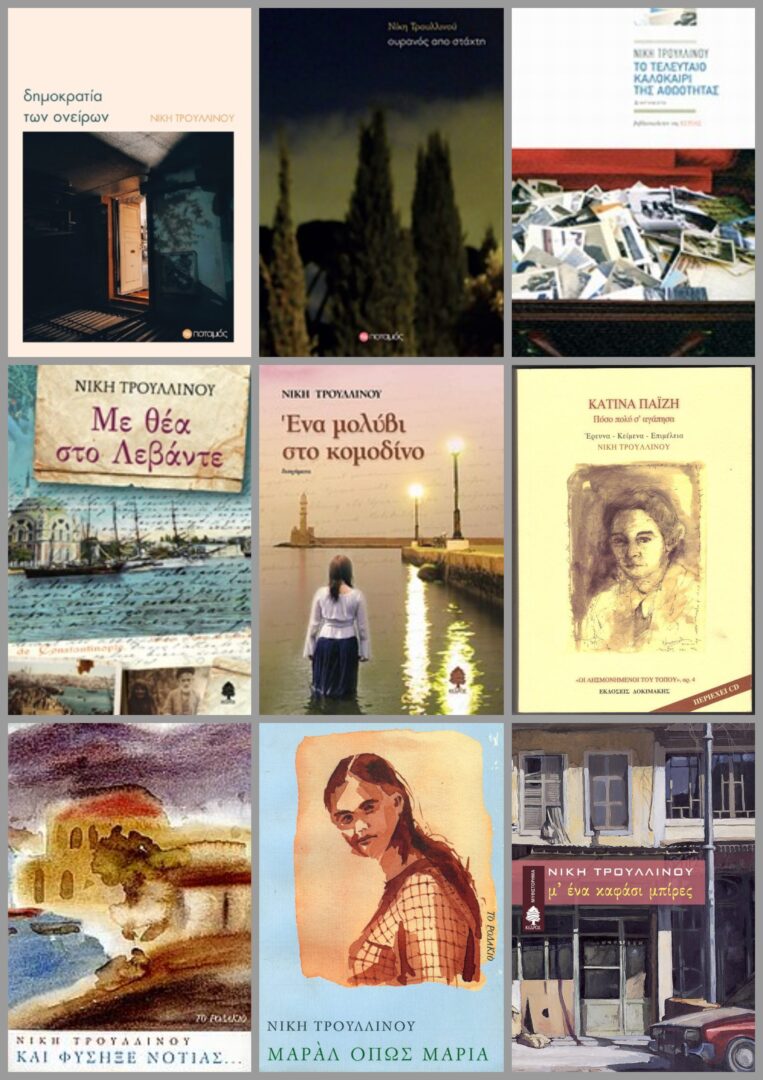

Niki Troullinou was born in Chania, Crete, and lives in Heraklion. She studied Law in Athens, worked as a lawyer, went through education, theater, radio, rural tourism. Her first appearance in literature was in 1995, with the short story collection A pencil on the bedside table; she then disappeared and returned seven years later with the book Maral like Maria. She has published seven short story collections, two novels, theater, essays and travelogues. She writes in numerous literary magazines and newspapers. She is a member of the Ηellenic Authors’ Society and Pen Greece.

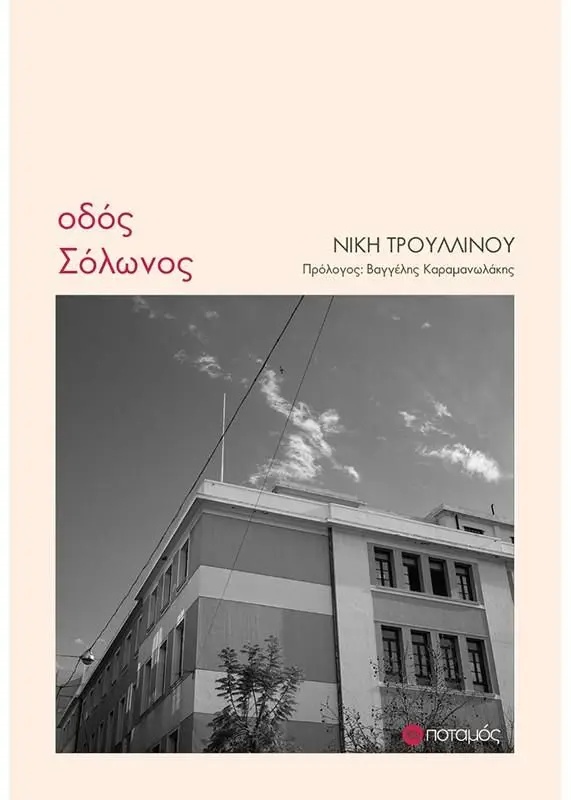

Your latest writing venture Οδός Σόλωνος [Solonos Street] was recently published by Potamos Editions. Tell us a few things about the book.

The book you refer to is titled after the well-known main street of Athens where there is located the Law School at which I was a student during the last three years of the dictatorship. It includes nineteen short stories, some previously published and several new ones. The reason, or rather my need, for this book has to do with time – half a century since the events of both 1973 and the advent of democracy in 1974. Memory was my need. Memory in a time of trampled dreams, frustrations and disappointments. As far time is concerned. the stories range from the adolescent memories of 1967 to the atmosphere and struggles of the anti-dictatorship student movement. And a little later.

How are the notions of memory, nostalgia, the past and its impact on the present are imprinted on your work?

First of all, I would say that I try to avoid nostalgia. It seems to me that as a concept, how shall I put it, it is quite heterochronic. Whatever happened was what it was; it made its impact, in one way or another, yet it belongs to the past – it doesn’t change. What remains is the imprint that accompanies us, what made us more or less mature as human beings, the ‘baggage’ of the past and how we carry it with us. And at the same time how we process this past so that we do not forget while also looking forward. It matters which values still haunt you and how they are subtly reflected in your writings.

More generally, how does literature converse with its surrounding environment? Could literature be used to shed light on the past and at the same time envision a radically different future?

You know, I often think of the obvious: that the past is present, as is the future. No matter how much external circumstances, frameworks, historical events, places, even social systems change, the human condition remains the same – love, death, loss in whatever mask it may wear, how we stand in relation to events and Nature, empathy and concern for the Other. And at the same time, our need to write literature. Without any attempt to teach, with no sterile homeland knowledge, just with respect to words and emotions.

You have stated that you are interested in the micro-stories of everyday people. Is this a way to narrate an alternative history of the world?

I don’t know what to tell you, I don’t know if I’m narrating an “alternative” history of the world; that’s a long conversation. And besides, it’s nothing new, literature is made up of stories of everyday people, people next door. It’s just that History is written without regard to the stories of these people. History commemorates emperors and generals, politicians and spies, battles and wars, conquests; it’s just that in the core of them all lie ordinary people.

You know, returning recently from three airports, I was observing the ‘invisible’ people: the cleaners, the waiters, the parking attendants, the workers at the ticket and customs counters, the sellers. Who actually cares about them? Yet, aren’t the ones moving the economy around? And the world, in that matter? No matter how rich, no matter how great and famous, is there a man or a woman that can exist without these ”invisible” ordinary people? I use the word ”invisible” since I observed passengers in airports: we do not look at the cleaners in the toilets, as if their existence is taken for granted and at the same time becomes indifferent – not even a thank you.

What about language? What role does language play in your writings?

Language is not just important, it’s pivotal. For centuries writers have been writing the same things; it’s how you write them that matters, at least that’s what I try to do. Literature is an art of speech – as simple as that – it’s not a newspaper, it’s not a food recipe or a medical prescription, it’s not a pamphlet nor a proclamation, not even a political document. If need be, all these things will be incorporated into the literary text, except that each and every one of us should, with respect to the art of speech, do so with special care to language. Of course, this care requires its own measure, its own charm, its own need to create images that dig a little into the reader; yes, I believe in the emotion that a text can evoke, as long as it knows where to stand.

I find what is often called the “pleasure” of a text quite shallow. A literary text can hurt us, upset us, take us on journeys and quests beyond mere pleasure. And words are the weapon. As long as they imply, they self-deride, they are left suspended in such a way that leaves room for the reader to see, to find their own engagement with the text.

Novels, short stories, essays, travelogues. Which do you consider to be the binding thread?

Perhaps the author’s eye and her attempt to win readers not always by the easy way of a quick read. That’s what I demand as a reader as well – a tough bet, no doubt.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE