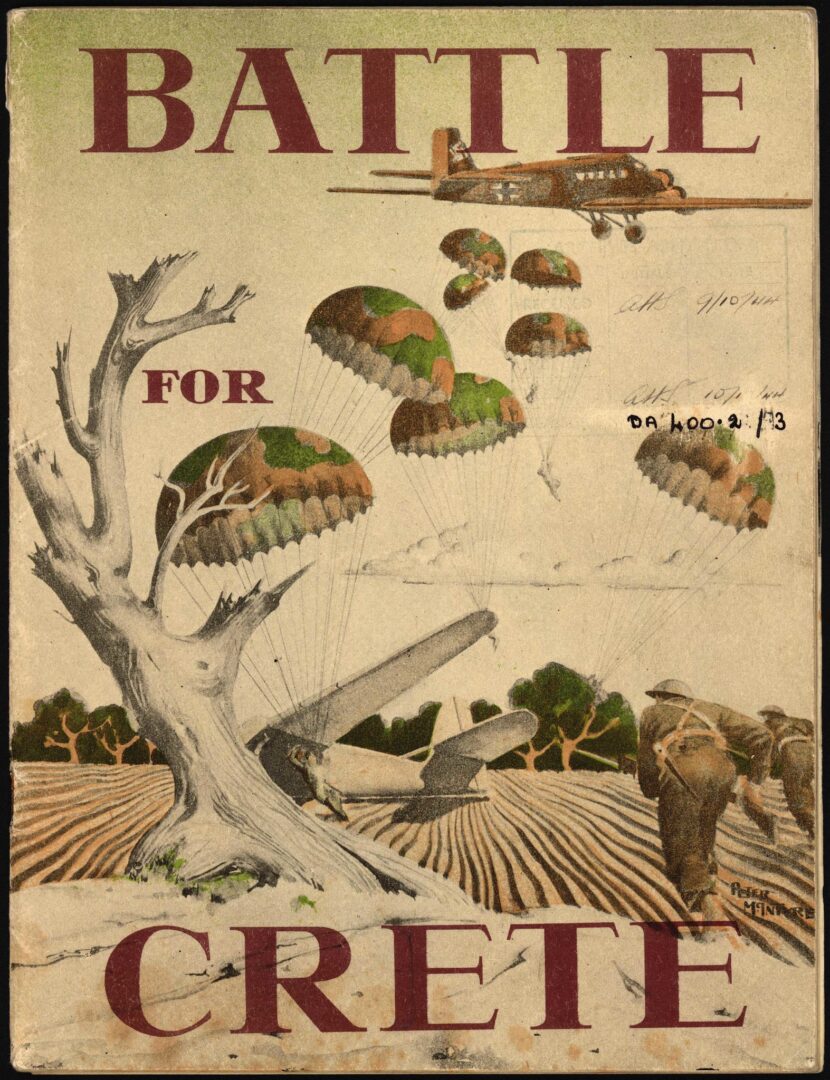

The Battle of Crete (also referred to as “Battle for Crete”) took place from 20 May until 1 June 1941, between the Allied Forces and the Axis powers; the Greek island of Crete was fiercely defended against the Axis invasion, as part of the German invasion of Greece in World War II. Crete would eventually fall in the hands of the Nazi army – but their heroic resistance of the Greek and Allied soldiers is an enduring symbol of courage and tenacity. Hundreds of soldiers from the UK, Australia and New Zealand remain buried in a cemetery in Crete.

Greece in World War II

Greece entered World War II on 28 October 1940, after Italy’s fascist leader, Benito Mussolini, issued an ultimatum to Greece, demanding free passage for his troops to occupy strategic points in its territory. Greece rejected the ultimatum, declaring war and, a few hours later, the Italian offensive against Greece began. (It should be noted that this date is one of Greece’s two national holidays, known as the “Ohi Day” [The day of “No”].)

The Greek Army successfully repelled the Italian assault, and in fact launched a victorious counteroffensive. Italy’s defeat in the Greco-Italian War compelled its German allies to intervene, starting the invasion of Greece on 6 April 1941 (“Operation Marita”). Grossly outnumbered –despite a small reinforcement from British and Commonwealth forces– the Greek army was unable to fend off the ruthless attack by the combined German and Italian powers, especially given the German air supremacy. Mainland Greece had been conquered by the end of April, with its only free part being the island of Crete in the south.

Operation Mercury

The Crete campaign, led by the Axis powers under the code name “Operation Mercury” (Unternehmen Merkur), began on 20 May 1941. It was of great strategic importance for the Axis to take hold of Crete due to its habours, commanding shipping lanes to the Black Sea and the Middle East, and its airfields.

The British forces had already garrisoned Crete during the Greco-Italian War, as the Royal Navy found its harbours and airfields useful for the war against the Axis. With the British taking over the defense of the island, the Cretan Division was transferred to the Albanian front where it participated in the January–February offensives against the Italians. Only three battalions had remained in Crete; the rest of the air assault brigade was unable to return to Crete following the retreat of the Greek army during Operation Marita.

The British were aware of the German plans for the invasion of Crete thanks to the breaking of Enigma codes. The combined British, Australian and New Zealand forces amounted to about 30,000, under the command of Lieutenant General Bernard Freyberg; together with the Greek soldiers, they clearly outnumbered the Germans. However, the latter still had aerial superiority, while the defending forces lacked heavy weapons. The Germans decided to make the most of their advantage, launching an airborne attack with glider and parachute forces.

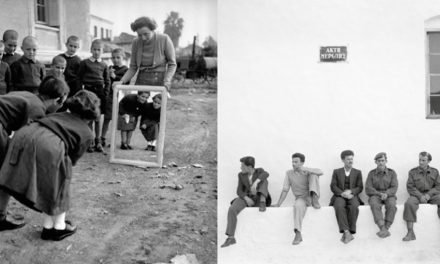

They did not however expect the ferocious resistance they would encounter not only from the defending soldiers but also from the Cretan civilians. About 9,350 troops landed on the first day, but German casualties were overwhelming. At the Maleme Airfield (in the nothwest), defended by New Zealanders, and the nearby town of Chania, defended by Greek forces, German paratroopers and gliders faced the most severe casualties. Greek resistance was equally fierce at the capital city of Heraklion and the town of Rethymno, in central Crete.

Among the Australian and New Zealand soldiers, many were indigenous people of the Australian continent – most notably the 28th (Māori) Battalion (Te Hokowhitu a Tū), a light infantry battalion of the New Zealand Army, which had previously fought at the Battle of Greece (even fighting at the legendary position of Thermopylae). At the Battle of Crete, they became famous for their bayonet charges against the enemy, letting out fierce Haka war cries.

On the days that followed, the Germans continued their attacks from the air, using paratroopers, and aerial and artillery bombardment; they also launched landing attempts using their war ships, which had to face the British Royal Navy. Italians also had to send reinforcements, who arrived in the last days.

Despite the unparalleled valiance demonstrated by the island’s defending forces, the continued attacks and extensive use of heavy weaponry eventually helped the German army advance and inflict serious damage on the allied forces. The Royal Navy suffered heavy losses and its eastern Mediterranean strength were virtually depleted. On the 26, Lieutenant General Freyberg ordered a general retreat to the south of the island to prepare for evacuation. From 28 May to 1 June, troops were embarked for Egypt; however, thousands of both Commonwealth and Greek troops were still on the island on 1 June, when the island came under German control.

Aftermath

Despite the German’s eventual victory, Operation Mercury, the first invasion in history that took place predominantly using parachute and glider troops, was considered too costly in terms of war casualties, making Germans avoid large-scale airborne operations for the rest of the war. Members of the German armed forces that took part in the Battle of Crete between 20 and 27 May 1941 would later be awarded the Crete Cuff Band: it was the first time that such a military decoration was bestowed as a campaign award.

The Cretan civilians had fought against the enemy with all their strengths usings any means at their disposal – which often meant just farming tools and even kitchen utensils, together with old rifles. As the Nazi army eventually took over the island, multiple civilians were killed, many of them in retaliative mass executions. In total, several thousand Cretan civilians (including women and children) either died fending off the invasion, were killed in the crossfire, or were summarily executed in reprisal for the German casualties. Throughout the Axis occupation of Crete, many locals entered resistance groups; German reprisals for the participation of Cretans in the Resistance often included summary executions and the destruction of entire villages.

Thousands of British Commonwealth and Greek soldiers were also captured by the enemy, while some of the foreign soldiers managed to hide in the mountains and survive for some period thanks to the help of the locals. One notable case was that of Reg Saunders, the first Aboriginal Australian to be commissioned as an officer in the Australian Army: as part of the 2/7th Infantry Battalion, he fought in the area around Chania; later, taking rearguard actions to allow other units to be evacuated from the island, his own battalion was eventually left behind. He was among the few who evaded captivity, hiding out in the hills and adopting Cretan dress. He remained hidden for eleven months, with the help of the locals, until he was finally evacuated from southern Crete in May 1942, along with other Commonwealth soldiers who had also stayed hidden or had escaped from prison camps.

Today, the graves of many Commonwealth soldiers who lost their lives defending Crete against the Nazi army can be found at the Souda Bay War Cemetery, a military cemetery administered by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Designed by architect Louis de Soissons, it contains 731 World War II burials where the body was identified along with another 776 burials of bodies which are unable to be identified.

N.M. (Intro image: Lieutenant General Bernard Freyberg, command of the Allied forces during the Battle of Crete, gazes over the parapet of his dug-out in the direction of the German advance)

Photographs source (except where noted): Imperial War Museums via picryl © Public Domain

TAGS: HISTORY | MODERN GREEK HISTORY