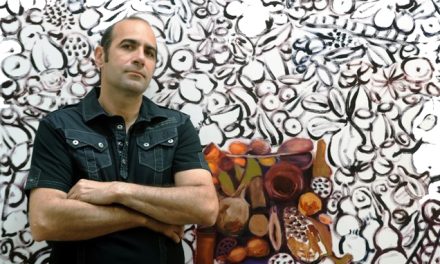

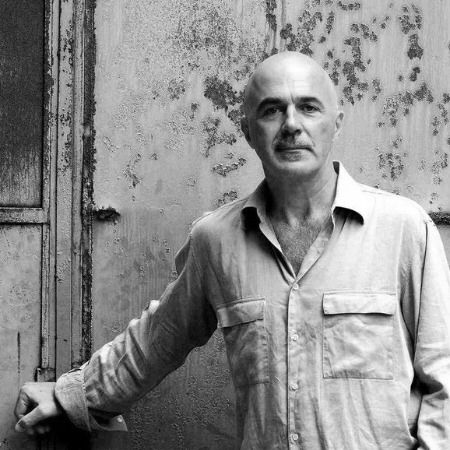

Stathis Livathinos is one of the most influential directors of his generation. Former artistic director of the National Theater of Greece (2015-2019) and its Experimental Stage (2001-2007), he is especially known for his works with his acting company, which celebrates its 25th anniversary this year. In June 2025, Stathis Livathinos was appointed a full member of the Academy of Athens to occupy the new Chair of Theater Arts.

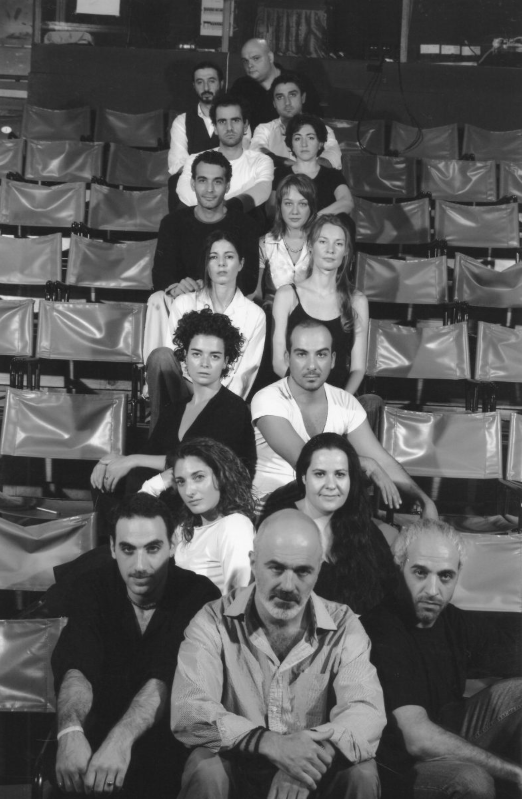

From 2001 to 2007, Stathis Livathinos was artistic director of the Experimental Stage of the National Theater of Greece, where he launched an innovative educational initiative with the creation of Greece’s first laboratory for theatrical direction. It was during this period that, through the laboratory’s productions, an acting company with a relatively stable composition was formed, celebrating its 25th anniversary this year.

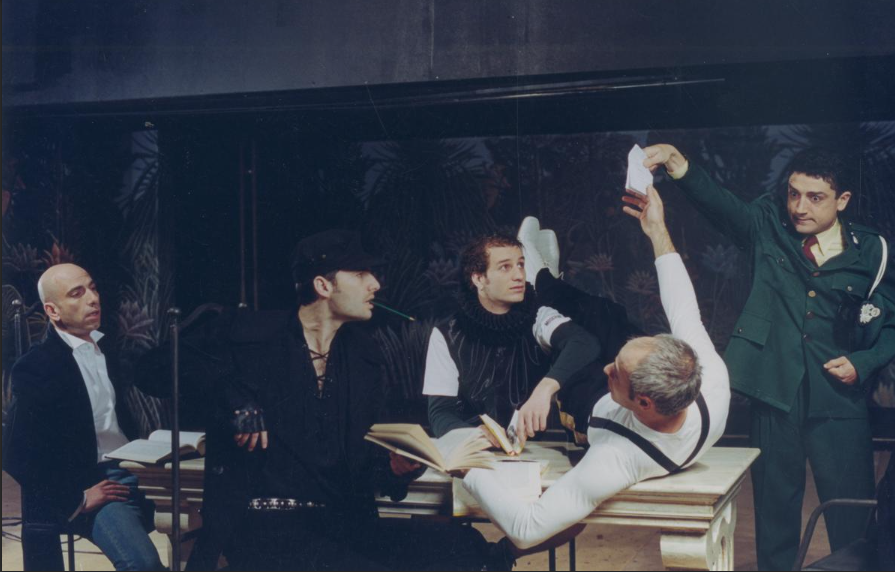

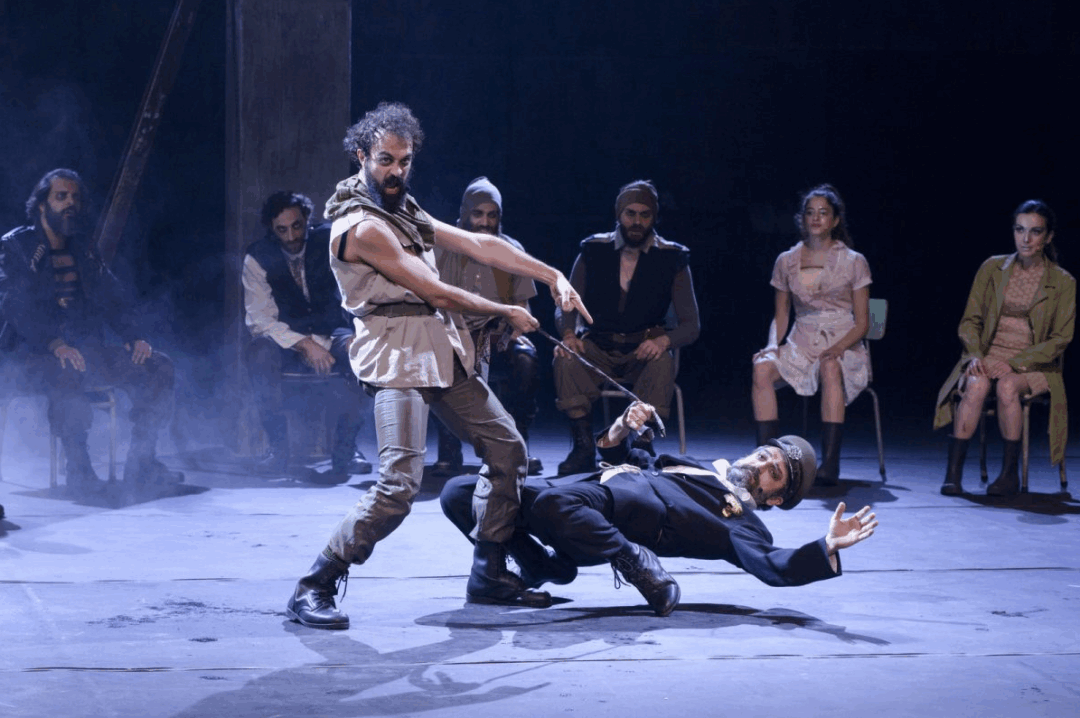

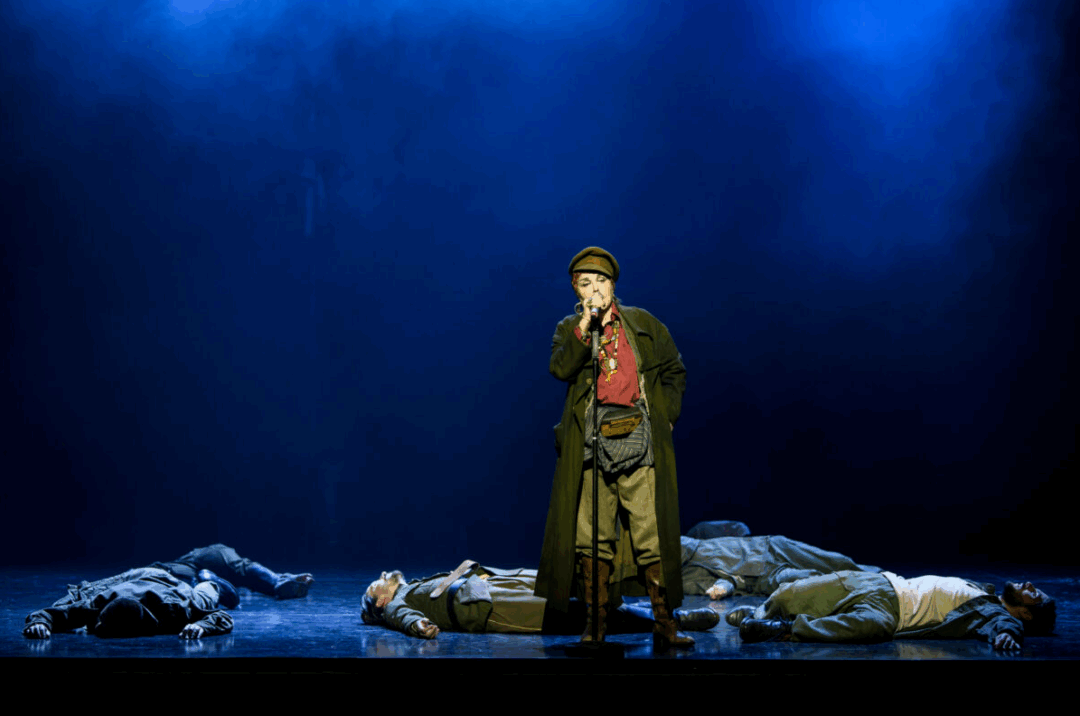

Livathinos has collaborated with Greece’s most important theatrical institutions (National Theater, Athens and Epidaurus Festival, Kefallinias St. Theater, Megaron Athens Concert Hall, etc.) and has directed some of the most notable productions of recent years, most of them with his troupe, including: Shakespeare’s Love ‘s Labour’s Lost (2002), It Never Ends: Greek Poetry of the 20th Century (2002-3), Euripides’ Medea (2003), Bulgakov’s Moliere (The Cabal of Hypocrites) (2004), Strindberg’s A Dream Play (2005), Dostoevsky’s The Idiot (2007-8 and 2012), Vitsentzos Kornaros’ Erotokritos (2011), Homer’s Iliad (2013) -which toured to international acclaim-, William Shakespeare and Thomas Middleton’s Timon of Athens (2017), Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz (2022), Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (2024), and Carlo Gozzi’s Turandot (2025). At the end of October 2025, Livathinos and his troupe will stage a production of Costas Taktsis’ The Third Wedding at the Greek Art Theatre Karolos Koun.

Our sister publication, GrèceHebdo, interviewed the director regarding his views on the art and ephemeral nature of theater, the importance of collective work and the timelessness of classical works.

On the occasion of the establishment of a Chair of Theater Arts at the Academy of Athens, to which you have been elected, I would like to ask you what this signifies for theater arts in Greece, on a broader basis.

It is true that theater does not require academic chairs to survive. It has survived without them even at the extremes of society and history.

However, any recognition and appreciation of theater as an institution is a positive step because, as I said in my acceptance speech, it validates its course, the struggle and the tireless efforts of so many generations of people from a time when theater was synonymous with frivolous entertainment.

The creation of the first academic chair for theater in Greece, the country where theater was born, is on the one hand symbolic, regardless of who occupies it (whether it’s me now or someone else tomorrow), and on the other hand can hopefully contribute to setting the conditions for interesting interventions, studies, and research, from which theater can only benefit.

That’s what I want to believe, always looking at the bright side. I do that because that’s how I am, and my personal goal is to make the most of all the potential opportunities that this academic chair offers, first of all in the field of education, especially theatrical education, a topic that interests me a lot. We’re still at the start, but I already have many ideas, many thoughts, and it remains to be seen how all this will work out.

Speaking of the birthplace of Greek theater: we are a few steps away from the Theatet of Dionysus, considered to be the first theatre in the world, founded at the time of Athenian democracy. Why and how is the birth of theater connected to the Athenian democracy, why was it born here, at that specific time?

I don’t think it could be any other way. It turns out that when a society reaches its heyday, it is in need of a mirror, an unsparing, accurate mirror. It is no coincidence that in very important periods of civilization, theater was always there.

I am neither a theater theorist nor a philologist, but what I can definitely say is that for theater to develop as an art, there need to have been phases of human evolution that inspire awe. Especially with regards to the evolution of spatiality, the concept of a public exchange of ideas and the birth of dialogue. Theater was not born on its own, but with it came literature, philosophy and -what’s most important, since it encompasses all the above- language itself evolved with it.

And language is what keeps us alive in Greece. Because our history is full of surprises, setbacks and interruptions. But language preserves a continuity. This is a huge tool in theater, which -I believe and will always say it- is a national product. It is not simply a work of art, like, say, a painting or a piece of music.

Theater is a national product. It is directly connected to the nature of the people of each nation, who create it and perform it, and with their language.

I would like to ask you, what is theater for you? What is its contribution to the way we ask or answer life’s questions?

Thankfully, theater deals with great issues that never concern just one person. They have to do with the fascinating, difficult and often tragic path of humans on earth. That is why certain works manage to survive and transcend the narrow limits of their time.

At the same time, when we observe life, we see that we need theater and mimesis to offer people something more, something that contains a different appreciation of life. Theater offers something extra, without losing sight of what is vital and fundamental. For me, theater is always an interesting, exciting game, but with great substance.

Are the great issues you mentioned the same issues that are the subject of philosophy? What is it that ultimately makes classic works timeless, whether it is Homer and ancient drama or Shakespeare?

Our lives are permeated and defined by specific issues that can be counted on the fingers of one hand. Usually they are love, death, creation, doubt…

But strangely enough, our lives are governed by small things. Our short lives pass in this fatal contradiction. And on this fact, I think, theater forms its own questions every time. Theater does not provide answers, because there are no answers in life. Life is a way someone asks questions and feels human because they think, because they are curious, because they wonder, because they are not satisfied…

Let’s turn to what I would call, if you allow me, Stathis Livathinos’ “obsessions”, which are theater education and teamwork.

I wouldn’t use the word obsessions. I have the luxury of usually being able to choose -up until now at least- the people I work with.

The team I work with has been relatively stable for the last 25 years and I have witnessed notable young people evolve into great artists. But I have of course worked with other people as well, including Betty Arvaniti and the Kefallinias Str. Theater or the National Theater of Northern Greece, etc.

I’ve been able in general to choose interesting people to work without losing myself pursuing too many things. I have always wanted my collaborations to be limited and meet certain criteria to make I would call honest, living theater, regardless of whether I always succeed or not.

What are the criteria for this type of theater?

They involve doing research and working with people whose character, talent, approach to creation, indicate that we share a curiosity and an interest in values, such as teamwork. This is not to say that individuality is banished from our work, quite the contrary.

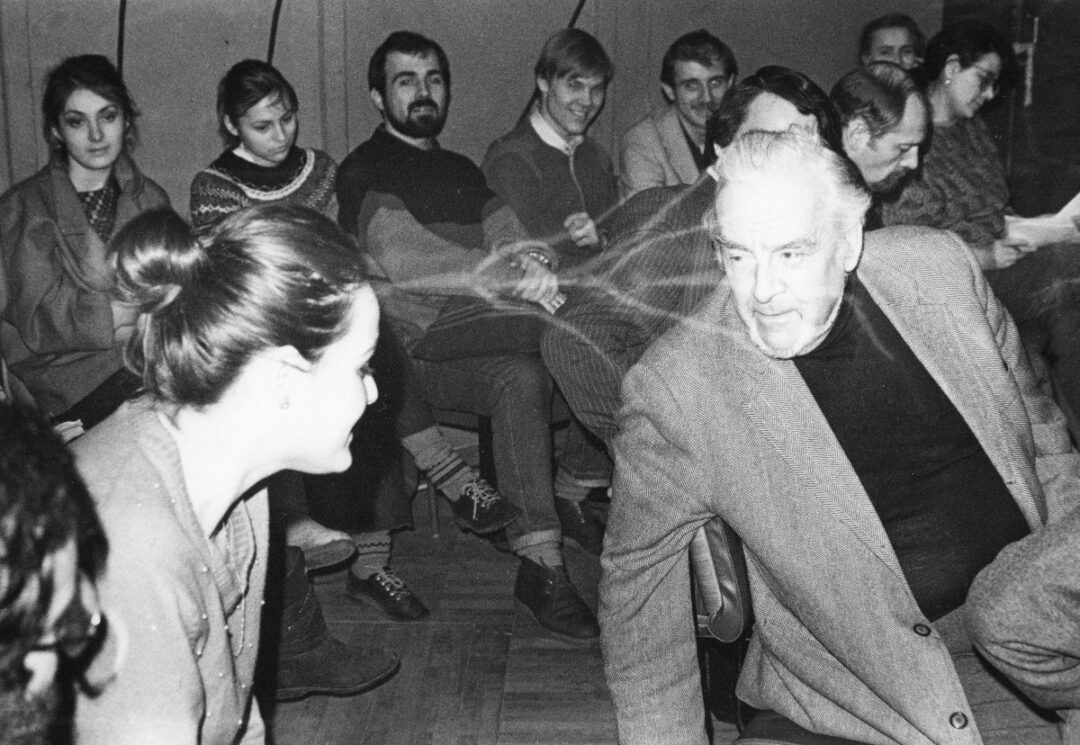

But I don’t believe I’m the first to engage myself with this kind of theater. This is what great stage directors, who I profoundly admire (like Strehler or Brook) have worked towards, and we shouldn’t forget that. Not to mention great Russian masters of theater, who taught dramatic art as a collective work, and tried to save theater from the pit of self-promotion.

This began at the start of the previous century. The effort to get theater out of what we call a pit.

What would you call “a pit“?

It’s the theater of the leading actor, the type that serves personal ambition and functions exclusively as a means of self-promotion. I am only interested in the kind of theater where even the last supporting actor will shine on stage, regardless of whether I always succeed to make that happen.

Would you say that this approach to theater changed thanks to the Russian method?

Yes, absolutely, that’s what really changed things. Although I think that the great figures in the history of theater, such as Molière for instance, also needed great and talented people to work with.

I believe that the more talented someone is, the more they wish to work alongside other talented people, instead of the opposite. I think this is more of less obvious if you look at the history of theater.

I consider it very cheap and petty to collaborate with people you consider inferior just so you can easily outshine them.

I think that real talent lies in being able to assert yourself among people from whom you have something to learn and with whom it is worthwhile sharing your secrets.

In your productions with you troupe, which celebrates its 25th anniversary this year, it is evident that a lot of hard work has been put into it, only to address an audience for a few hours. Is the ephemeral nature of theater -and fleeting time in general- an issue that you are concerned with?

I am always concerned by it, and nowadays we should be even more concerned, because we have found a powerful rival: image. Image as in those sweet, anodyne moments of scrolling, which can distance us from the charged moments of stage time.

We often find ourselves in a state of attention deficit.

Absolutely. And the things that tend to disappear in our days are those exact things that are essential for theater to function; and I believe that theater is what will ultimately preserve the humanity in us. Because time in the theater has real value; people are constantly trying to “buy” time, whereas a theatrical production takes place within a fixed time frame and demands total attention.

What’s more, moments on stage or an actor’s presence on stage are much more weightful, much more meaningful. A second on stage can be worth a century, while a second in everyday life can seem like nothing.

However, you are also concerned with the past. Judging by your recent book (Three Ages, Patakis Publishers, 2022), I think you want to honor the people who left their mark on you.

That is my true inheritance. And that is every person’s inheritance. It didn’t just appear out of thin air.

I was lucky enough to meet wonderful, remarkable people, and I feel very fortunate. Also, in a way, every person leaves something inside of us. If your life is meaningful and you give it substance, that leaves something inside of us. So yes, that’s what I wanted to write about.

Finally, drawing on the title of one of your productions with the National Theater’s Experimental Stage, It Never Ends: what is that which never ends, in theater, in life?

This title works on many levels. Language never ends, and neither does theater, after we go away.

Until the time comes when it all ends. And we know when that moment is, when we cease to exist and we return to where we started, and someone else takes our place. That too is a way that things go on.

What actually never ends is the mysterious, special, strange thread that is part of the vibrant and sensitive people who care about language, theater, the stage, and art.

TAGS: THEATRE