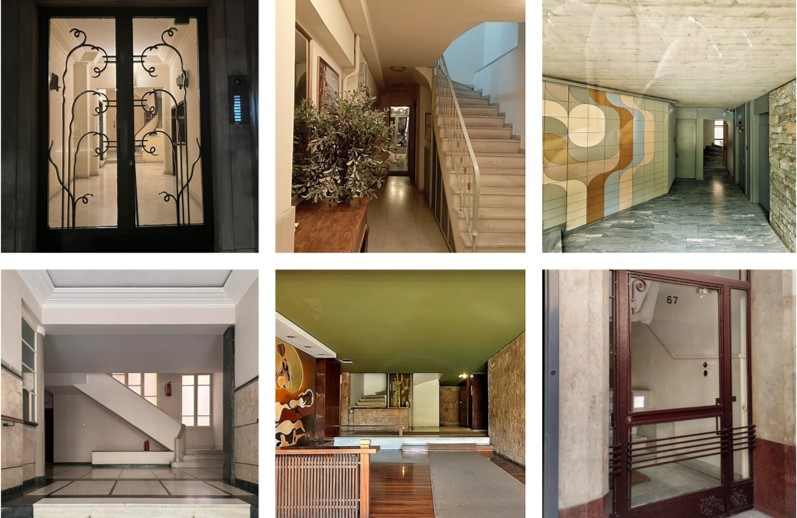

The modern city of Athens is often perceived as a concrete jungle filled with tall apartment buildings; this building type, the polykatoikía, and its omnipresence in the Greek capital, is often considered to be dreary and unartistic. In recent years, however, the polykatoikía has been the subject of a reappraisal by academics, architects and urban theorists. The architectural, social and economic significance of these modernist apartment blocks, which line one street after another, has been revisited in the light of historical and contemporary urban contexts. A more anthropocentric vision is therefore applied, highlighting values such as simplicity and accessibility, as well as the liveliness and sociability of the city.

Background: Modern architecture and Greek exoticism

In 1933, the Fourth Congress of the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM IV) was held in Athens, bringing together dozens of renowned architects from all over the world to discuss the new modern city of their time. Iconic architect Le Corbusier was among its organizers. The congress proved to be a turning point for modern Greek architecture, offering it a unique opportunity to define its identity in relation to the international avant-garde.

The conference culminated in the Athens Charter, which laid the foundation for urban planning based on four key functions: housing, work, recreation, and circulation. It advocated for the zoning of cities to improve living conditions, a concept that shaped post-war urban development.

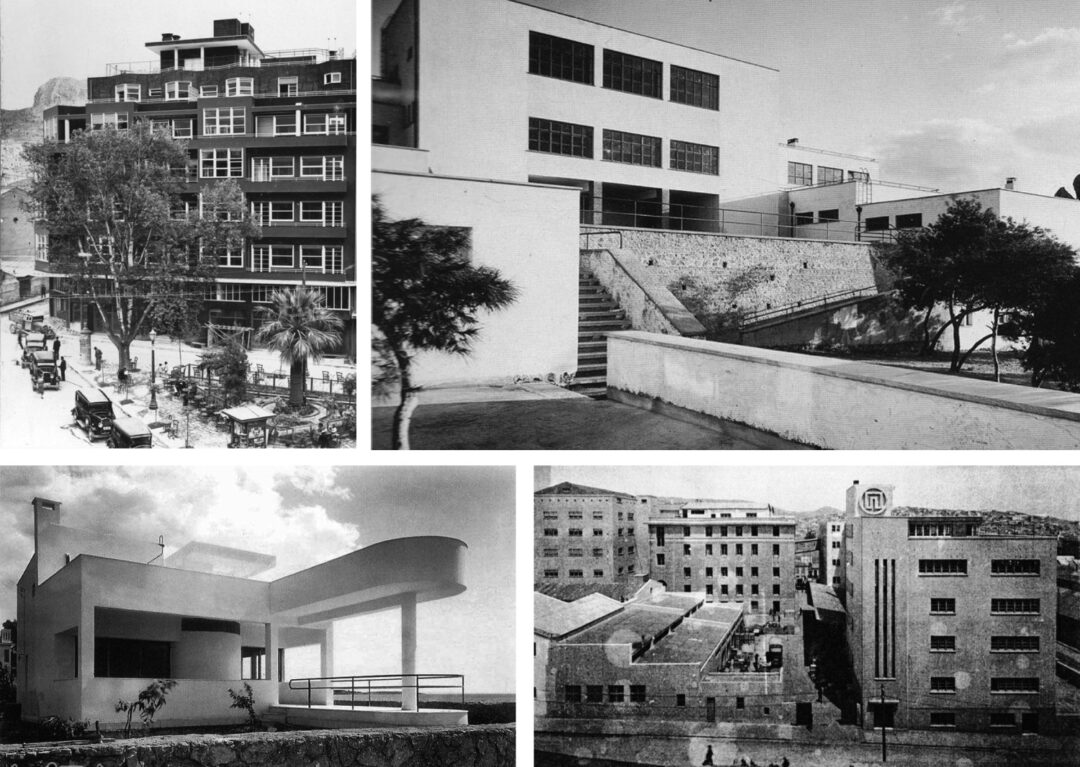

The urban sprawl of Athens, an ancient city that returned to prominence as the capital of the modern Greek state in the first half of the 19th century, was not the result of industrial development, but rather of a series of events that led to population flows to the big cities. Yet a number of important modern buildings (schools, residential buildings, factories etc.) had just been completed in Athens.

Greek architects’ faith in modern architecture was also demonstrated in an imaginative way by connecting modern architecture with traditional Greek architecture, which at the time seemed exotic to everyone. Greek architectural features (particularly those of the Cycladic islands) such as simple structures, abstract forms, absence of decoration, emphasis on functionality, etc. were considered modernist characteristics, if not the foundation of modernism (Kostas Tsiambaos, 2020 [in Greek]).

Photo: Dimitris Harisiadis. Benaki Museum Photo Archives

“Antiparochi”: the way to apartment building supremacy

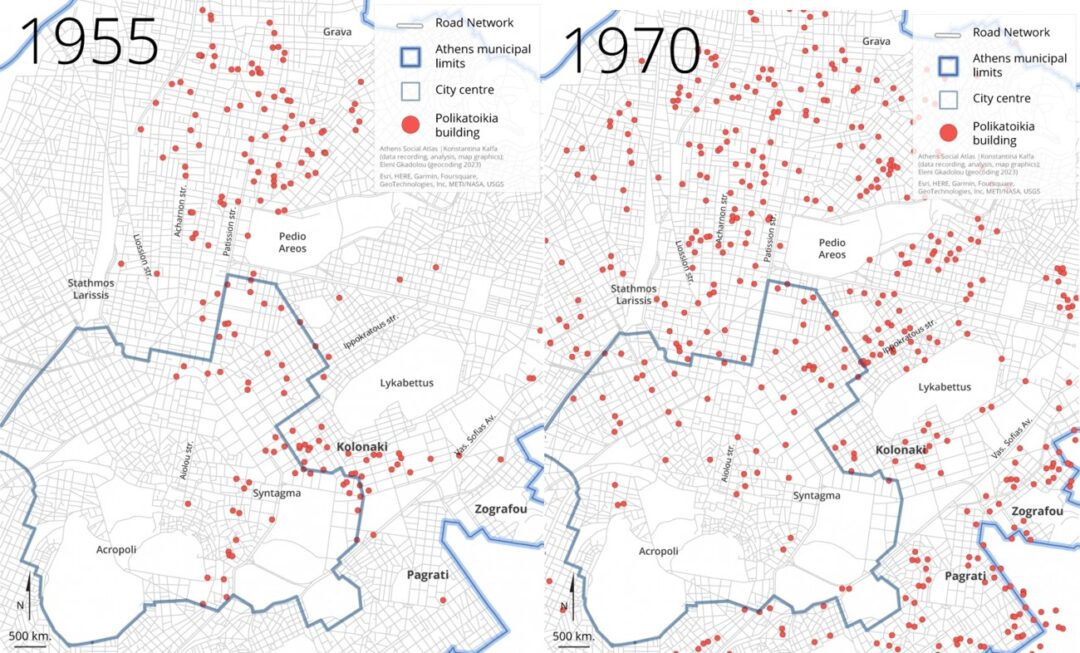

In the post-war period, the Greek Civil War of 1946-49, together with a shift from rural work to industrial labor, led to a continued migration from the countryside to the big cities. This created an urgent need for housing, leading to the intense urbanization of the Greek capital after 1950. During this period and until the late 1970s, the population of Athens’ metropolitan area more than doubled, with the entire city experiencing an unprecedented construction boom.

In the central neighborhoods of Athens it was difficult to find enough space for the construction of apartment buildings. The 1929 law of horizontal ownership helped create the system of antiparochi, which could be roughly translated as “counter-providing”: a landowner could turn over a plot of land to a constructor, who would build a where a polykatoikía where one or two-story house used to stand. In return, they would gain ownership of an agreed number of apartments in the finished building. Given that the Greek state could not afford to directly finance a social housing program, this system helped give the working classes access to low-cost housing. (By way of illustration, in 2011, 93.3% of the population of the municipality of Athens lived in multi-storey buildings, 75.5% of which were built before 1980.)

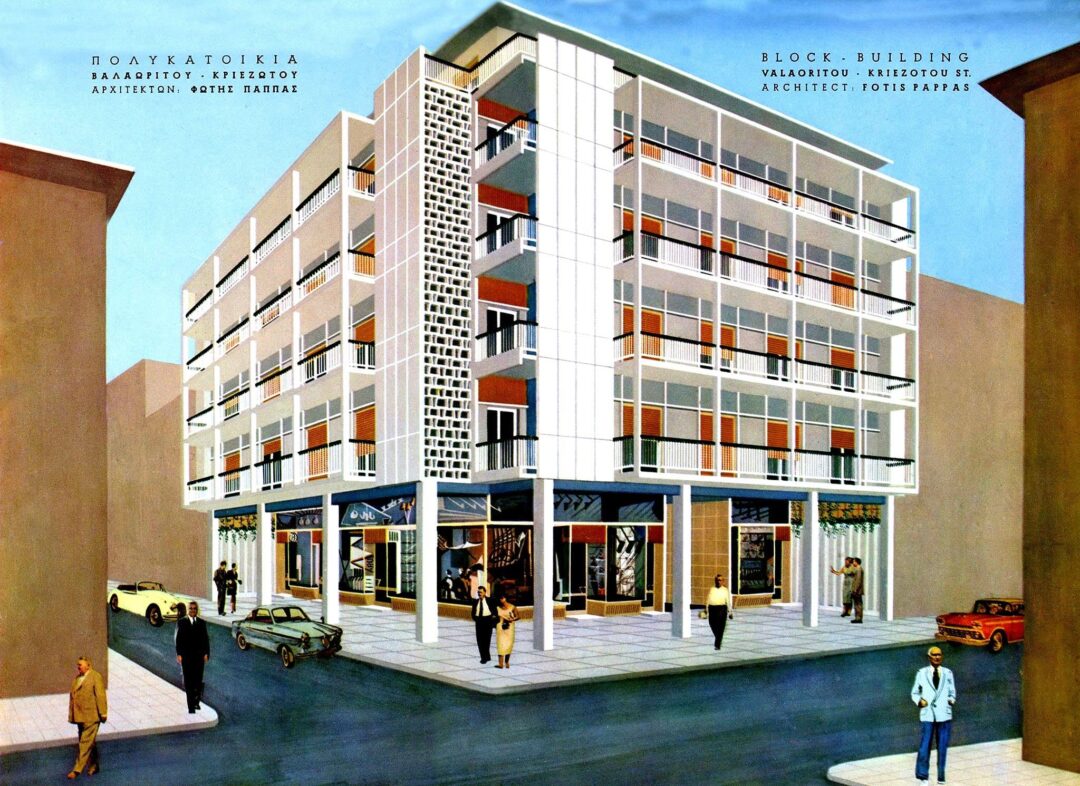

Whereas the multi-storey buildings of the inter-war period were designed by renowned architects such as Kitsikis, Nikolaidis and Panagiotakos, who sought to develop a modern urban typology using decorative forms from Art Deco, Bauhaus and Cubism, the polykatoikía of the post-war period became a product of real estate speculation for building contractors. Easily reproducible thanks to standardized plans, quick to erect and simple to finance, it became widespread as a type of housing for the working classes.

Building contractors would build apartment buildings, often selling the apartments before construction was completed; the first plans were drawn up in order to obtain a building permit, sometimes with minimal input from an architect, whose name did not always appear on official documents. These plans were based on “turnkey” sketches that could be easily adapted to a wide variety of situations (Olga Moatsou-Ess, 2018).

Even this period, however, saw the creation of some important buildings by renowned architects of the time such as Valsamakis, Konstantinidis and Tombazis. These types of polykatoikía, addressed at the upper classes, were featured in leading architectural journals, introducing a European-influenced modernity that helped shape a new generation of Greek architects.

From strong criticism to reappraisal

The antiparochi system has been much lamented, blamed for the architectural homogenization and even the perceived “ugliness” of Athens – and the rest of Greece’s large urban centers. It should be noted that the absence of state planning of urban development, particularly during the 1960s-1970s, contributed to a lack of urban cohesion, with negative impacts on both aesthetics and the environment.

The houses formerly occupying the sites where uniform concrete apartment blocks would be built were often residential houses of the neoclassical rhythm; neoclassicism was the first architectural style introduced in Athens. Some of the most important buildings of the late 19th and early 20th century are still preserved today. However, the vast majority of the less historic ones vanished as a result of the construction boom.

Nostalgia for a time when small streets were lined with quaint houses, and neighbors could sit and chat in backyards full of flower pots, often makes people hostile towards the bleak facades of concrete apartment buildings. However, in their reminiscences, people tend to overlook the fact that many of the older buildings, especially the smaller ones where poorer families resided, were far from what one would call comfortable: the electricity grid was often rudimentary, there was no central heating and often no proper bathrooms – the lavatory was usually an outhouse and people would often bathe in small tubs filled with water from the sink. The then-new apartment buildings didn’t just offer affordable housing, but also a good quality of life.

Source: FB Page “History of Engineering and Construction in (1836-2014)”

This attitude is however slowly changing. As journalist Harry van Versendaal points out, the “stereotypical image of the Greek capital as a cluttered concrete jungle, has, in recent years, undergone a reappraisal […] Scholars, architects and urban theorists have increasingly reevaluated the architectural, social and economic significance of these modernist apartment buildings”.

This reevaluation is reflected in various publications and events, such as Goethe Institute’s exhibition Athens’ Polykatoikias 1930-1975: Formation of a Typology; addressing the opening of the exhibition, Myrto Kiourti, an award-winning Athens-based architect, said that, thanks to the values of Modern architecture, “Athens achieved one of Modernism’s main goals: decent housing for all”.

According to British architect, critic and historian Kenneth Frampton, the apartment block in Athens is a unique modern manifestation of urban development, resulting from the spontaneous evolution of society, rather than from planned intervention.

The Athenian polykatoikía has been the subject of the Ioanna Theocharopoulou’s book Builders, Housewives and the Construction of Modern Athens (Onassis Publications, 2022), which offers a critical re-evaluation of the city as a successful adaptation to circumstance, enriching our understanding of urbanism as a truly collective design activity. Theocharopoulou, an architect and architectural historian, re-evaluates the polykatoikía as a low-tech, easily constructible innovation that stimulated the postwar urban economy, triggering the city’s social mid-twentieth-century transformation.

According to her, the process of creating a broader middle class through real estate development contributed to the reduction of the social, ideological and cultural divides of the interwar period, as well as healing the wounds of the civil war.

Inspired by Theocharopoulou’s book, a documentary of the same title has been made by film directors Tassos Langis and Yiannis Gaitanidis. As they stated, they used the book as a starting point and guide as they “delved into the cracks of our modern urban history to trace the internal immigrants who were the ‘co-authors’ of our built environment”.

Builders, Housewives and the Construction of Modern Athens at the Onassis Channel on YouTube:

Athenian modernism once more at the forefront

A different take on the Athenian urban landscape was identified as early as the 2000s. Impressively, Greece’s participation in the 2002 Venice Biennale was entitled “Athens 2002: Absolute Realism”. Athenian modernism is once again in the spotlight, but no longer through “official” modernism. It is not the image of a tourist Athens that is showcased, but the anonymous, graffitied, marginal and even “ugly” aspects of the city.

In 2016 the online platform “Social Atlas of Athens” was created with the aim of highlighting and recording the social geography of Athens. The platform, supported by the Onassis Foundation, aims to raise awareness of the key structures and processes shaping the city’s social fabric.

Similarly, research at pan-European level has begun to treat Athens’ “anonymous” modernity differently. Doctoral theses and research projects at leading institutions in Europe and America (Richard Woditsch, Olga Moatsou, Plato Isaias, Ioanna Theocharopoulou etc.), were now discussing the common and typical Athenian apartment building in terms of an alternative, “marginal” modernity, one that distanced itself from the experience of the developed world.

Theocharopoulou, for example, introduces new conceptual tools to document the particularities of this development, drawing on a number of different sources, which are not limited to the architectural and urban history of Athens but extend to social history, anthropology, gender studies, the evolution of language and the study of shadow theater.

For its advocates, the concept of polykatoikía ultimately embodies the fundamental philosophy of modernist architecture: “Form follows function” – the appearance and structure of a building must be determined first and foremost by its use and purpose. As they point out: “The true beauty of a city lies in the way it is inhabited. Athens is an attractive city. However, it is attractive not because of its beautiful buildings, but because of its attractive way of life.”

N.M. (Partly based on the article “The ‘polykatoikia’ of the 1960s-1970s as an essential element of Athens’ “anonymous” modernity” which appeared on Grèce Hebdo)

Read also via Greek News Agenda: The Fourth CIAM Congress of 1933 in Athens and the foundations of Western urbanism; Open House Athens: “Future Heritage: The Architecture of Today, the Heritage of Tomorrow”; Bookshelf: Exploring Greek Architecture

TAGS: ARCHITECTURE | ATHENS | HERITAGE