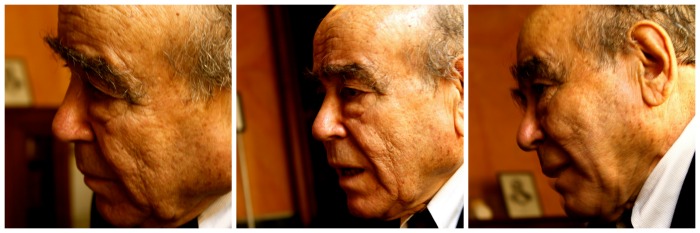

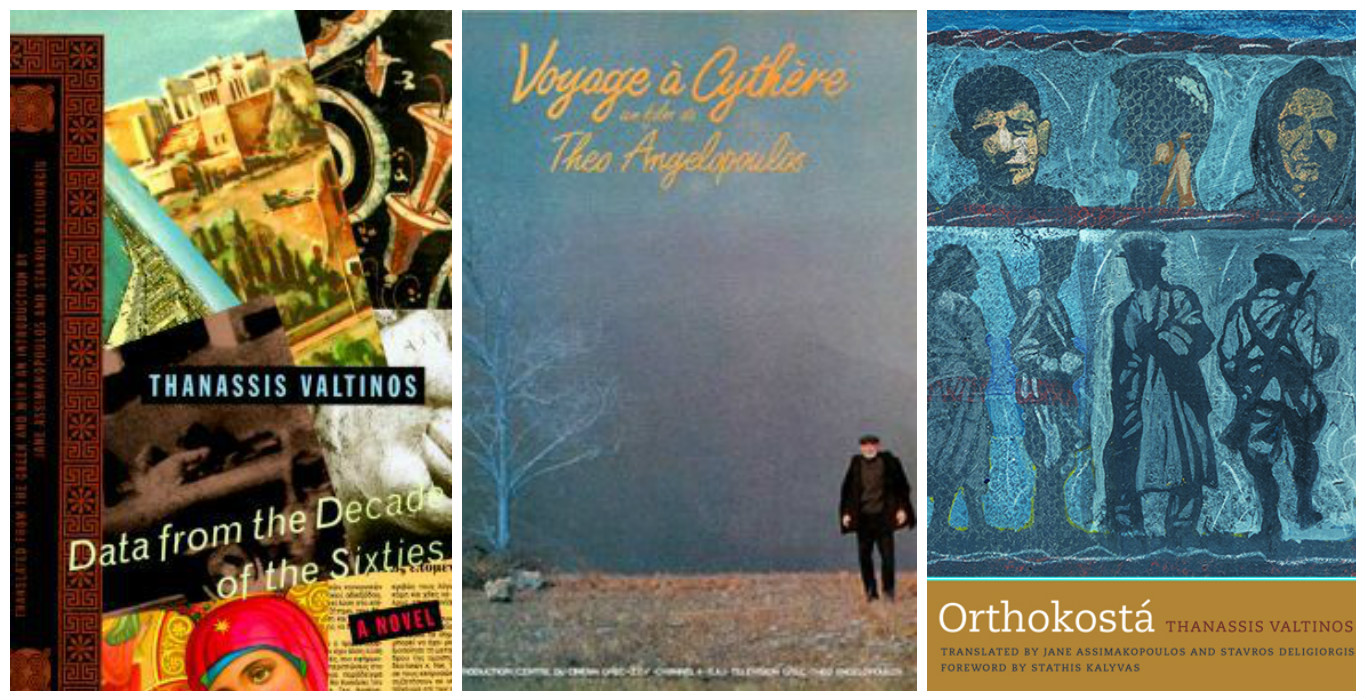

A Peloponnesian highlander by birth (born in the mountainous village of Kastri, in the region of Arcadia in 1932), the President of the Academy of Athens Thanasis Valtinos was at primary school when the Nazi invasion of 1941 threw Greek provincial life into disarray, soon followed by protracted civil war. He migrated to Athens in 1950 and studied cinematography. The brutality surrounding his formative years haunted the fiction he began to publish sporadically from the late 1950s onwards. His literary output gathered pace in the 1970s, interspersed with translations of ancient drama and well received screenplays directed by Karolos Koun. He has also written film scripts in collaboration with film director Theodoros Angelopoulos, most notably the award-winning Voyage to Kythira (1984). His novel Data from the Decade of the Sixties won the National Book Award for Best Novel in 1990. The publication of Orthokosta (1994) was followed by many reviews and articles in the literary and daily press (the “Orthokosta controversy“) which announced the beginning of a larger and complex debate about the Greek 40s and Greek Civil War, which still continues in Greece.

Thanasis Valtinos has been president of the Hellenic Authors’ Society and has been elected in the Chair of Prosewriting at the Academy of Athens in 2010. He has been translated into many languages and his inaugural address to the Academy (The Last Varlamis) was recently published in English by Birmingham Modern Greek Translations, while Orthokosta will be published this summer by Yale University Press with an introduction by Political Science Professor Stathis Kalyvas.

Thanasis Valtinos spoke to Greek News Agenda and Grece Hebdo* about his life and literary work, Greek society and the Greek “ordinary man”.

Which of your books would you suggest for readers who would like to get acquainted with your work?

This is an unexpected question. No doubt my books are linked to history and a certain chronological order. So I would suggest The Legendary of Andreas Kordopatis (1972) that focuses on the beginning of the 20th century.

Among your books which one is your favorite?

I would say that I certainly have preferences considering my books, but I cannot talk about them, just like a mother cannot publicly admit which one is her preferred child.

Should literature respect the historical truth?

Literature and history refer to two different worlds. But when literature uses history for non-literary purposes, the result is bad literature. However, a writer should take account of the historical truth in order to construct his own “truth”, that is the literary truth.

Common people occupy a central place in your work. Why?

I’m not interested in heroic figures. What really attracts me is the ordinary man, the everyday man who has experienced suffering.

What has happened to this ordinary man after the dictatorship?

I think he has changed following the transformation of Greek society as a whole. I keep the memory of the common people who were spontaneous and who knew how to sing and dance. They have become mere radio listeners and TV watchers losing their capacity to communicate and express themselves in an authentic way. They have “softened” and absorbed by consumerism. Their “liberation” took a wrong direction, one that lacks spiritual discipline. As a nation, I don’t know if we can nowadays produce the kind of consensus and common spirit that we once produced, for example at the time of the Axis invasion in 1940. During the current crisis, common people became victims of manipulation by political elites and they seem to react only occasionally as it is the case of the protests regarding pension reductions. Literature can certainly play here a certain role here but the number of the people that are really interested is limited and bad literature is gaining ground.

How did you become a man of letters and literature?

It was rather a matter of coincidence. We went through our adolescence without being properly guided by the school of the time. Our teachers were not educated enough or able enough to guide us toward reading quality Modern Greek literature and poetry e.g. Seferis or Elytis. When, by pure chance, I started to read Kazantzakis, I was dazzled. And then I started to frequent Tripoli’s (capital of the region of Arcadia) public library, where I read the work of Grigorios Xenopoulos as well as France’s pornographic literature. But without help or guidance from anyone.

What does it mean for you to be a Greek highlander?

My formative years in the Peloponnese were marked by the German occupation and the civil war. I have developed a highlander’s capacity to hold up in the face of adversity.

What do you mostly appreciate in Greece and the Greeks?

Few things, but they are things that I like enormously.

For example?

The sense of simplicity and direct reaction to difficult situations. And the dignity which is especially visible in people of a certain age.

And what is your political orientation in general?

I followed my family’s tradition, which was located at the centre of the political spectrum. I was also influenced by certain texts that I found fascinating, among which the Bible – I consider the Old Testament as one of the most poetic and erotic texts, as well as Greek demotic songs and melancholy love songs and laments on death (mirologia). And I should certainly add, the memories of the soldiers of the war of independence against the Ottomans, namely Kolokotronis and Nikitaras.

What are your plans concerning the Academy of Athens?

As President of the Academy, I want to open the Academy to the public through seminars, literature and art presentations so that it is no longer regarded as a closed and obsolete monastery. However, the lack of financial resources remains a major problem.

* Interview by Nikolas Nenedakis (Greek News Agenda), Costas Mavroidis and Magdalini Varoucha (Grèce Hebdo) in the presence of the poet Yiorgos Chouliaras.

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS