Christmas Holidays are a time for family and friends to gather around a festive table set with sweet and savoury delicacies; in Greece, this will usually include some type of white or red meat, potatoes, salads and, for dessert, melomakarona (syrup-soaked cookies) and kourabiedes (sugar-coated shortbreads) – but, for New Year’s Day, the pièce de résistance is the vasilopita!

The vasilopita

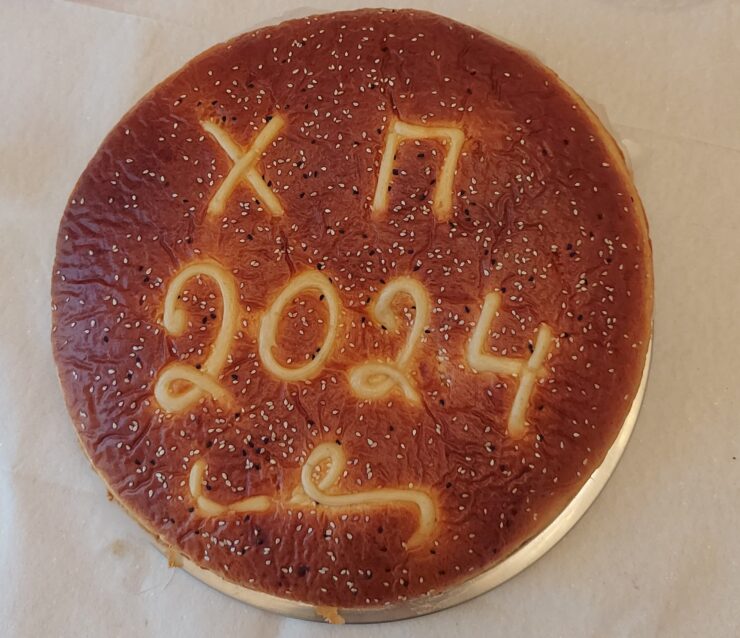

The vasilopita is a flour confection to celebrate the New Year. When it is prepared, a coin called flouri (a medieval word for florin, a gold coin from Florence) is hidden in the batter, usually before it is baked. A piece is served to each person present at the gathering for the New Year, and the person who finds the flouri in their piece is supposed to have a lucky year, and is often also offered a small gift – traditionally in the form of a good luck charm called gouri. A piece is also customarily sliced for Jesus Christ and/or for Saint Basil, as well as for the household where the gathering takes place.

A pound cake-style vasilopita (Via Wikimedia Commons)

A pound cake-style vasilopita (Via Wikimedia Commons)

The dessert is often served at the end of the festive meal on New Year’s Day, usually at noon. However, a New Year’s Eve party will almost always include the slicing of a vasilopita, shortly after the year changes. Most Greeks will have one vasilopita for the New Year’s réveillon, which is often celebrated with friends, and another for the New Year’s Day lunch, usually spent with family members. Aside from private houses, vasilopita parties are also generally held by companies, offices and workplaces in general, and also by associations, societies, clubs etc.

In keeping with the Greek culinary tradition, the typical vasilopita has the taste and consistency of a sweet bread very similar to the famous tsoureki (leavened bread with milk, sugar, egg and butter), made with yeast dough and flavoured with mastiha (mastic resin) and mahleb spice. However, vasilopita made using a recipe similar to that for pound cake has been increasingly popular in the latest decades, as it is easier to make and very popular with the younger generations.

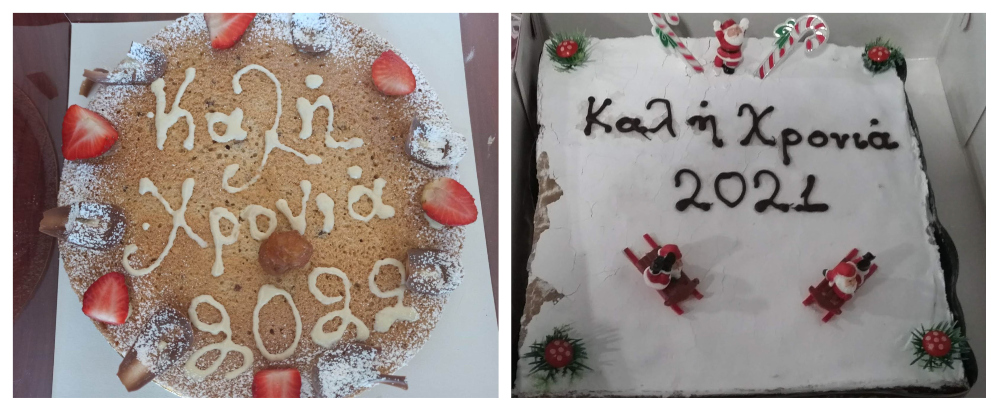

A “politiki”-style vasilopita

A vasilopita is often dusted with a thick layer of powdered sugar or covered in sugar icing or in chocolate. The New Year numbers are often written on it using almonds, chocolate or sugar icing, marzipan or, more traditionally, pomegranate seeds, while it can also have other decorations. To this day, many are those who prefer to bake their own home-made vasilopita, sometimes using a family recipe passed on for generations, although of course, ever more often, people choose a store-bought one, with many shops –from traditional bakeries to ultra-modern confectionery stores– offering countless options.

Apart from the traditional Greek vasilopita, which can either be like a typical tsoureki or have a denser, more bread-like consistency –called politiki, meaning “Constantinople-style”, and considered the quintessential vasilopita– there are many local variations, depending on the region. These are often pies (an omnipresent dish in traditional Greek cuisine), usually with a savoury filling. For example, a chicken pie is often prepared in Thessaly, a meat pie in Thrace and a cheese or leek pie in Kavala. In some cases, the savoury pie is used for the New Year’s Eve feast, while the classic sweet-bread vasilopita is cut on New Year’s lunch. On the island of Zakynthos, on the other hand, a kouloura is used: it is a wine-based Bundt-shaped raisin bread and it is cut on Christmas Eve.

Store-bought vasilopitas (photo by Marianna Arvaniti)

Store-bought vasilopitas (photo by Marianna Arvaniti)

Saint Basil

The vasilopita tradition is reminiscent the King Cake tradition that can be found in many areas across Europe (such as the British Twelfth Cake, the French galette des rois or the Spanish roscón de reyes) and other parts of the world (such as the New Orleans King Cake) where a token is almost invariably hidden in the dessert, bringing good fortune to the finder. These customs are believed to draw their origins from the Roman era, and more specifically from the festival of Saturnalia.

The main difference with the vasilopita is that the Kings Cake is almost invariably consumed on the feast of the Epiphany which, according to Western Christianity, commemorates the visit of the Magi to the Christ Child – hence the name Kings (or Three Kings) Cake. The Greek version, on the other hand, is linked of Basil of Caesarea, whose feast day is on the 1st of January.

The main difference with the vasilopita is that the Kings Cake is almost invariably consumed on the feast of the Epiphany which, according to Western Christianity, commemorates the visit of the Magi to the Christ Child – hence the name Kings (or Three Kings) Cake. The Greek version, on the other hand, is linked of Basil of Caesarea, whose feast day is on the 1st of January.

Even the word vasilopita, which could be taken to signify “kings’s pie”, is instead supposed to mean “Basil’s pie” – since the Greek name Vassilios is directly descended from the word vassileus (“king”). The saint is particularly revered in Greek tradition; instead of Santa Klaus (a personification of Christmas derived from the actual Saint Nicolas), the international figure of Father Christmas is in fact identified as Saint Basil in Greece and, because of that, holiday gifts are traditionally exchanged on New Year’s Day (the saint’s feast) instead of Christmas.

Basil of Caesarea, also called Saint Basil the Great (330 – 379), was a famous and influential theologian, and the bishop of Caesarea in Cappadocia, Asia Minor. He was known for his generosity towards the underprivileged; he organised a soup kitchen and distributed food to the poor during a famine following a drought, and he gave away his personal family inheritance to benefit the poor of his diocese. For this reason, he has come to be regarded as the bearer of holiday time gifts.

There are also stories in Greek Orthodox tradition which are meant to explain the custom of vasilopita. According to some versions, the bishop’s flock had gathered their heirlooms and given them to him in order to pay some heavy taxes or to save their city from being sacked; the valuables would eventually be saved by divine intervention or by the death of an evil king, and, trying to figure out a way to return them to their rightful owners, Saint Basil would make his deacons bake many loaves of bread, hiding an object in each one. The breads would then be handed out to the people, and each person would magically discover, in the loaf they took, the same item they had previously given up.

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Greek and Roman origins of Christmas traditions; Chestnuts: One of Greece’s Winter Delicacies

N.M. (Intro image source: ANA-MPA)