This year marks the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne, a treaty that defined the borders of modern Turkey, and is a key point of reference in Greece’s relations with Turkey. On this occasion, the Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP) and the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens co-organized a two-day International Conference under the title “100 Years since the Treaty of Lausanne: Looking Back, Looking Ahead“, which took place on 12 and 13 June 2023, featuring 10 discussion panels, and with the participation of 43 academics, researchers, diplomats and experts representing all the state signatories to the Treaty.

The Conference was held under the auspices of H.E. the President of the Hellenic Republic, Ms. Katerina Sakellaropoulou, who laid out its aims in her opening speech on June 12, noting that “The Treaty of Lausanne is indeed a landmark treaty, which established the national borders in our neighborhood and in the Middle East, with the aim of restoring peace after the devastating WWI. The centenary of its signature is an excellent opportunity to reaffirm its strength and the stable framework it created, which continues to be a pillar of peace in the region.”

Professor Loukas Tsoukalis, President of ELIAMEP, and Professor Meletios-Athanasios Dimopoulos, Rector of EKPA, addressed the welcoming speeches. Loukas Tsoukalis emphasized that “For Greece and Turkey, two neighbors with a difficult past, the Treaty of Lausanne was primarily a peace treaty that followed a long and bloody war. It provided the foundations for the peaceful coexistence of our two countries for several decades.” Meletios – Athanasios Dimopoulos commented “I cannot fail to recognize and emphasize the importance and durability of the Treaty of Lausanne, which is to this day a durable example of political innovation in terms of borders, geopolitics, populations, minorities and ideology.”

The first day’s work was structured around five speaker panels. The first panel dealt with the social and economic context around which the Treaty of Lausanne was formed. In this panel, the speakers are Evanthis Hatzivasiliou, Professor of Post-War History at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and Secretary General of the Parliament Foundation for Parliamentarianism and Democracy, explained that “The peace settlement that followed the First World War, including the Treaty of Lausanne, created a new international legitimacy as a pillar and integral part of a new, values-oriented liberal international system”. Şevket Pamuk, Professor of Economic History at Bogaziçi University recalled that “The Treaty of Lausanne played a decisive role in the emergence of a national economy in Turkey during the twentieth century. An important aspect of the negotiations in the economic field concerned the restructuring of the Ottoman debt”.

The second debate on June 12 had as its central theme the political and institutional framework of the Treaty of Lausanne. Evangelos Venizelos, Professor of Constitutional Law at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and former Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, noted that the Treaty of Lausanne was a treaty of defeat for both countries – for Greece defeat in the Greek-Turkish war (1919–1922), for Turkey defeat in World War I (1914-1918) – however, and at the same time it laid the foundation of national identity and statehood for both countries. Venizelos concluded that Lausanne can serve as a positive factor of rapprochement in current Greek-Turkish relations.

On the same panel, Konstantina Botsiou, Professor of History and International Relations the University of Piraeus and General Director at the Institute of International Relations (IDIS), characterized the population exchange between Greece and Turkey as a ‘cruel novelty’ that however served the national homogeneity between both countries. She remarked that the Lausanne Treaty, coupling defeat with independence, shaped the relations between Greece and Turkey on a basis of historical equality, making war between the two countries ‘a bad option’.

On the third discussion, on the issue of the Treaty of Lausanne for peace-building, Ayhan Aktar, Professor of Sociology (ret) in Istanbul Bilgi University, spoke about the three different state-narratives of Turkey in relation to the Treaty of Lausanne stressing that after the signing of the treaty the Turkish delegation presented Lausanne as a guarantor of independence and sovereignty, while in the 1960’s an anti-imperialist approach was adopted. Finally, an Islamic conservative narrative has emerged mainly since 2010’s -promoted also by popular historical TV dramas- claiming that the Treaty destroyed the Islamic past of Turkey and falsely asserting that the Treaty would end in 2023.

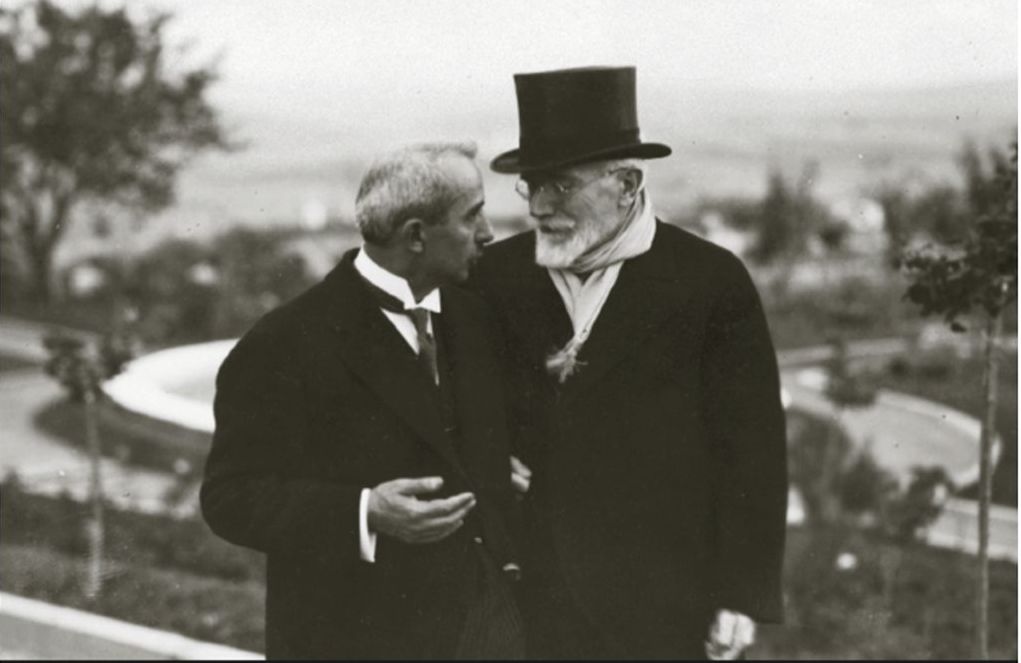

In the fourth panel, on the topic of the role of personalities in the formation of the Treaty, speaker Jonathan Conlin, Professor of Modern History e University of Southampton and co-founder of “The Lausanne Project“, reported that “After being sidelined in Paris in 1919, British Foreign Secretary George Nathaniel Curzon probably saw the Lausanne Conference of 1922 as an opportunity, which may have taken him all the way to Downing Street. İsmet was inexperienced in high diplomacy and the Americans thought they would have the opportunity to deliver lessons in how to handle the “Orientals” and George Mavrogordatos, Professor of Political Science (ret.) at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, emphasized that “At the Lausanne Peace Conference, Greece was both a country defeated by Turkey and an ally of the victors of the First World War. Only Eleftherios Venizelos, with his commanding presence, could take advantage of this contradiction and revive the spirit of the alliance, especially with Great Britain.”

The fifth panel dealt with the evolution of Greek and Turkish Foreign Policy; speaker Serhat Güvenç, Professor of International Relations at Kadir Has University, pointed out that more critical voices towards Lausanne are emerging in Turkey. According to Panagiotis Ioakeimidis, Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, there can be a win-win resolution of tensions between the two countries under the conditions that we seize the current positive momentum, apply a smart comprehensive strategy and involve the EU in a creative way.

The sixth discussion held on June 13, the second day of the conference, was on the subject of the role and politics of the Great Powers. Kanehara Atsuko, Professor of International Law at Sophia University and member of the Governing Board for UNIMO International Maritime Law Institute (IMLI), remarked that “the significant characteristic of the Treaty of Lausanne, with its comprehensive structure of the vast areas of issues included, consists in the wide coverage of regions on the globe represented by its party States: Europe, Near East, and Far East, according to the terminology at the time”.

The seventh panel dealt with the geopolitical implications and the new balance in the Middle East. Speaker George Prevelakis, Professor Emeritus, Panthéon-Sorbonne University (Paris 1) and Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Hellenic American University, spoke on the need to retain the memory of the Archipelago and the archipelagic way of life – a concept tied to the physical structure of the Mediterranean with its network of islands – a concept threatened in our current time of increased ‘maritimization of the world’ on the one hand, and the ‘territorialization of the sea’ on the other. On the same panel, Ioannis Grigoriadis, Associate Professor and Jean Monnet Chair of European Studies at Bilket Universtiy, pointed out that that the Lausanne Treaty was the end of the imperial project and the consolidation of the nation-state for both countries. He recalled that despite the fact that in the 1930s, the two countries had just exited a decade of bitter conflict, they were very quick in reestablishing friendly relations; Turkey and Greece were both status quo nations at the time, and what is more, they had common security concerns, which led them to cooperate on an number of issues.

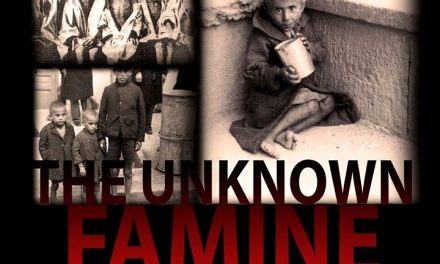

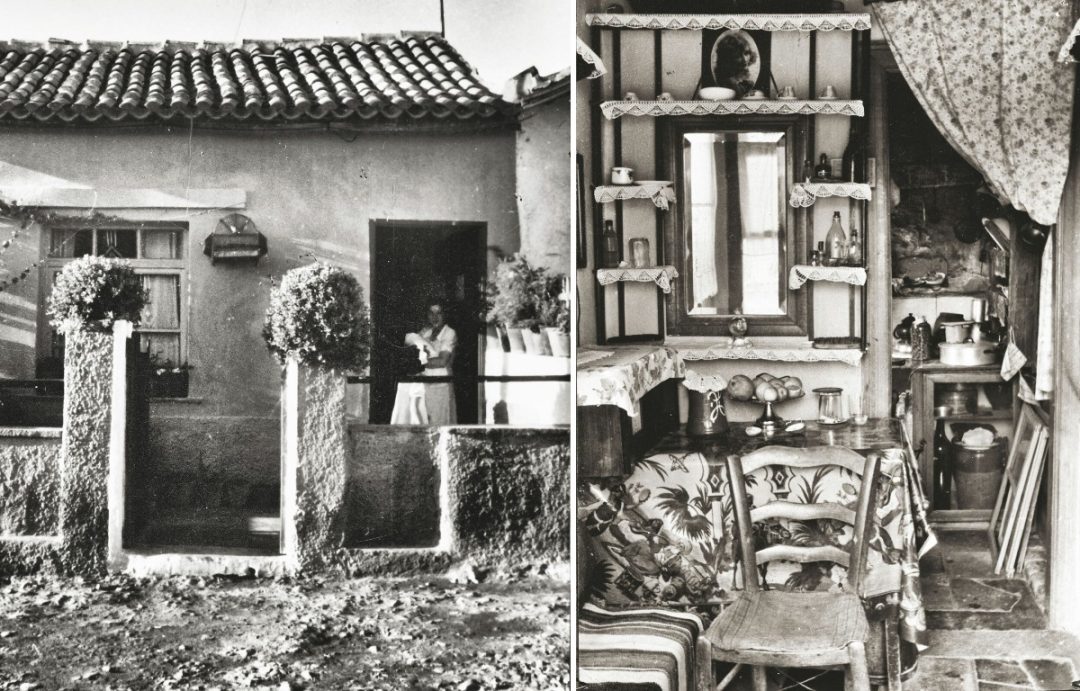

The eighth panel focused on the territorial, political, economic and social aspects of the formation of the new Greek state. Kalliopi Amygdalou, Senior Research Fellow at ELIAMEP, remarked that the settlement process of the more than 1.2 million Greek Orthodox refugees that were displaced, as a result of the 1919-1922 war and the 1923 Population Exchange, brought about a deep transformation of the urban and rural landscape of Greece, one that determined the shape and structure of whole cities, towns and villages up to this day. As Amygdalou concluded, the settlement of exchangees literally changed the face of Greece and the different ways in new settlements for exchangees were created reveals the interweaving of “memory, heritage and the politics of social welfare”, a dimension further studied in the ongoing research project HOMEACROSS – that looks at the material legacies and the refugees’ agency in shaping their surroundings in Izmir and Attica, two provinces that received large numbers of refugees during the Population Exchange.

On the ninth panel, a roundtable discussion on the significance of the Treaty today, Christos Rozakis, Professor Emeritus at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and former Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, pointed out that he Lausanne Treaty is primarily about defining boundaries between the warring sides and assigning territory to them; this makes it an objective agreement that retains its objective character beyond its life span and that has erga omnes results, meaning that it can also be invoked by and is binding for non-signatory parties.

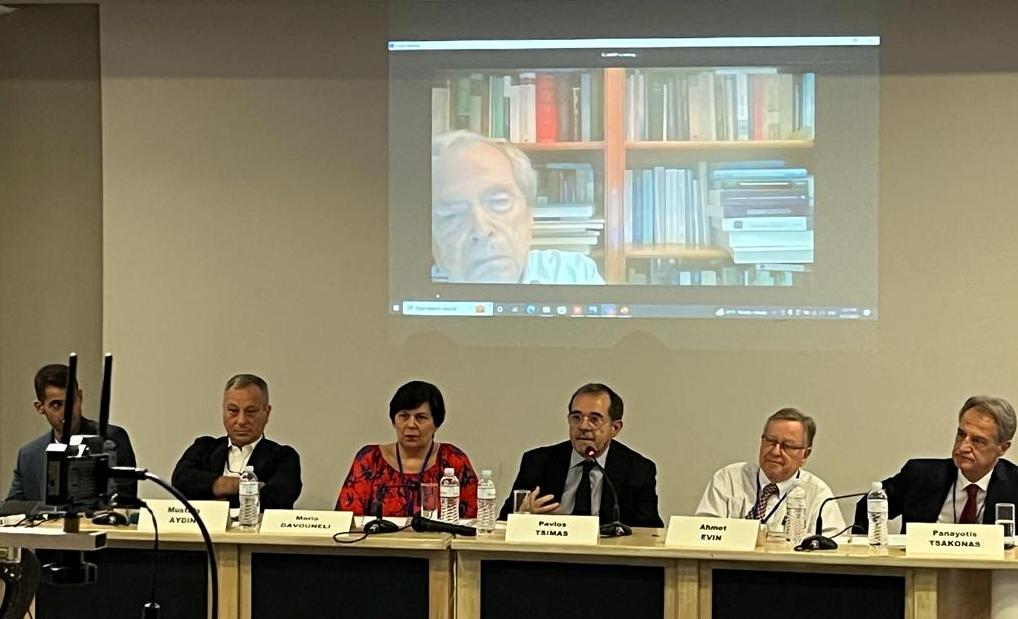

Maria Gavouneli, Professor of International Law at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and Director General of ELIAMEP, noted that “the Treaty of Lausanne was the tombstone of the Ottoman Empire and the end of the Oriental Question. It was also the birthing chair of the Republic of Turkey, and I have a feeling it may become the springboard for moving beyond territory and borders into other forms of soft (or not so soft) power.” Ahmet Evin, Professor Emeritus at Sabanci University and Senior Scholat at Istanbul Policy Center pointed out that “Today the Treaty retains its significance not only for Greece, Turkey, and the region, but also for the history of European conflicts that transformed the continent since the nineteenth century”.

Finally, Panayotis Tsakonas, Professor of International Relations at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, noted that today we find ourselves in a multilateral, unstable world, when poly-crises constitute the new normal in Eastern Mediterranean. Turkey stands further to the Lausanne Treaty, while Greece stands closer it; however today’s environment is averse to revisionism and expansion, which means that whatever agreement is reached will be on a rules-based regime. He further added that “The Lausanne Treaty has made evident two things that are of particular importance today. First, how a rules-based system can be built today based on compromises made between both states. Secondly, I found it particularly interesting how bilateral issues can be addressed through multicultural schemes.”

At the roundtable “The Lausanne Legacy-The Diplomats View”, with the participation of experienced diplomats, Pavlos Apostolidis, Greek Ambassador (ad hon.) referring to the Greek-Turkish rapprochement of the 1930s said that the Greek opposition at the time accused Venizelos of “giving too much” in Lausanne. Fatih Ceylan, Turkish Ambassador (ad hon.) said that we have to think outside the box starting to rebuild trust and confidence like in the 1930’s using all channels of dialogue as allies and neighbors. Elias Clis, Greek Ambassador (ad hon.) claimed that the Treaty of Lausanne is the base for Greek-Turkish relations and that Lausanne could be a paradigm for future discussions. Faruk Loğoğlu Turkish Ambassador (ad hon.) stressed that the Treaty of Lausanne is a living document and diplomatic masterpiece claiming that Greek – Turkish issues can be resolved based on wisdom and experience.

I.L.

TAGS: MODERN GREEK HISTORY