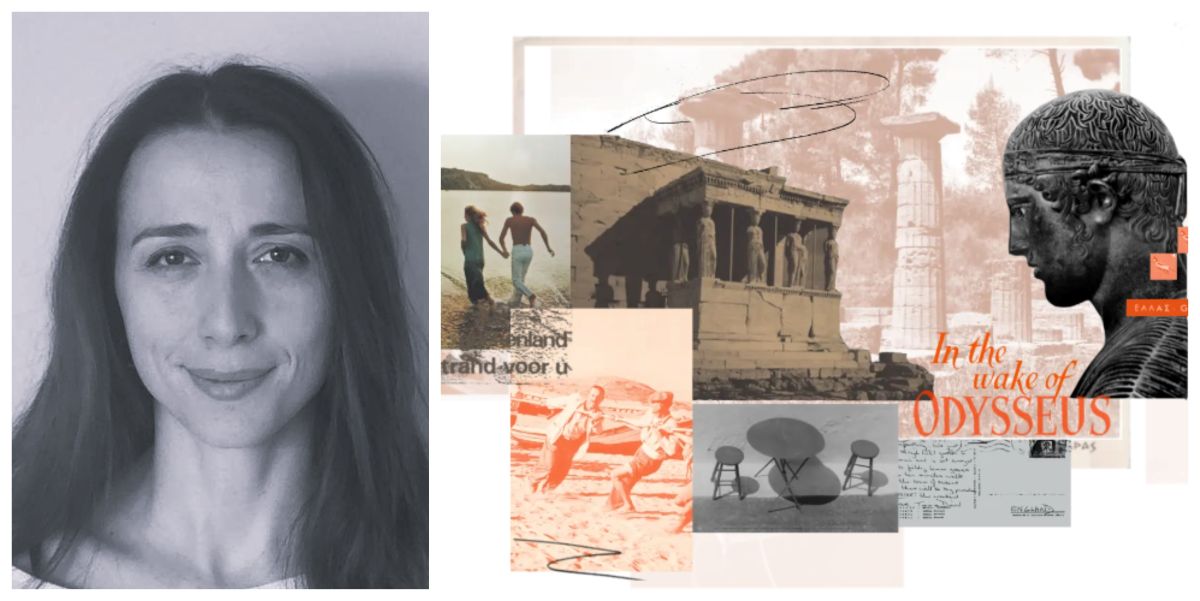

Eirini Karamouzi is Professor of Contemporary History at The American College of Greece and Associate Dean of Research and Innovation at the School of Liberal Arts and Science. She is also a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Sheffield. She is the author of Greece, the EEC and the Cold War: The Second Enlargement (2014), co-editor of The Balkans in the Cold War (2017) and Beyond the Euromissile Crisis: The Global histories of anti-nuclear activism (2024). Professor Karamouzi is also the principal investigator of the curating team for “Imagining Greece,” an evolving research-based exhibition that explores how social, political, and cultural forces have shaped Greece’s image as a tourist destination. Along with lead researchers and scientific and artistic Curators for Imagining Greece, Dr Stavros Alifragkis and Dr Emilia Athanasiou, professor Karamouzi spoke to Greek News Agenda* on the aspects of the Greek experience that “Imagining Greece” highlights for potential or past travelers, on the forces have shaped the global perception and image of Greece as an ideal place to visit, the major turning points in the modern history of Greek tourism and finally, on what the present and future holds for Greek tourism and on what constitutes a Southern European identity.

What is the central focus of the “Imagining Greece” project? Why is the period between the end of World War II and the end of the Cold War significant for tourism?

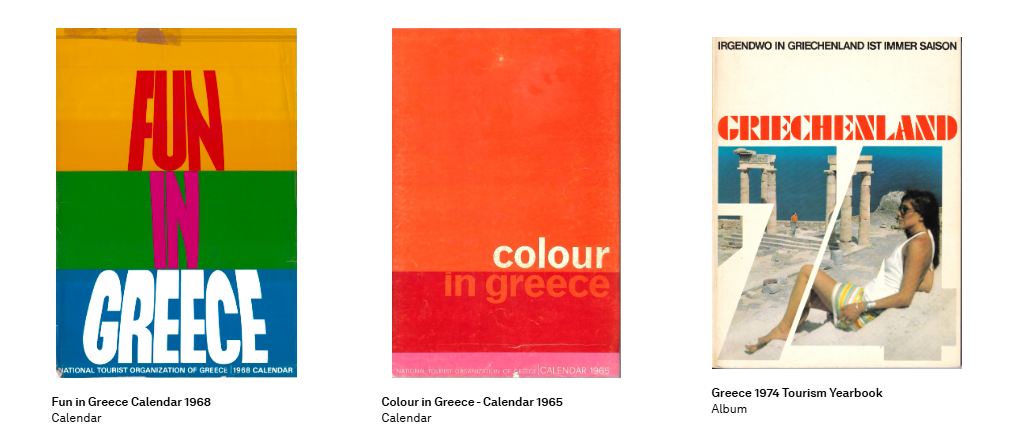

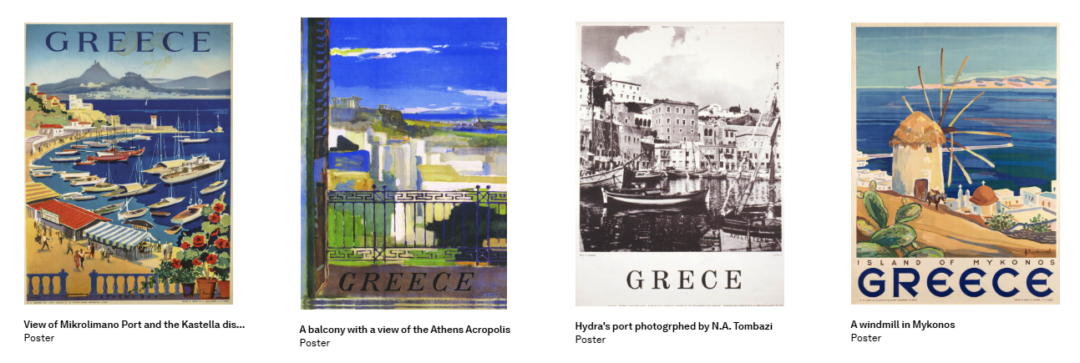

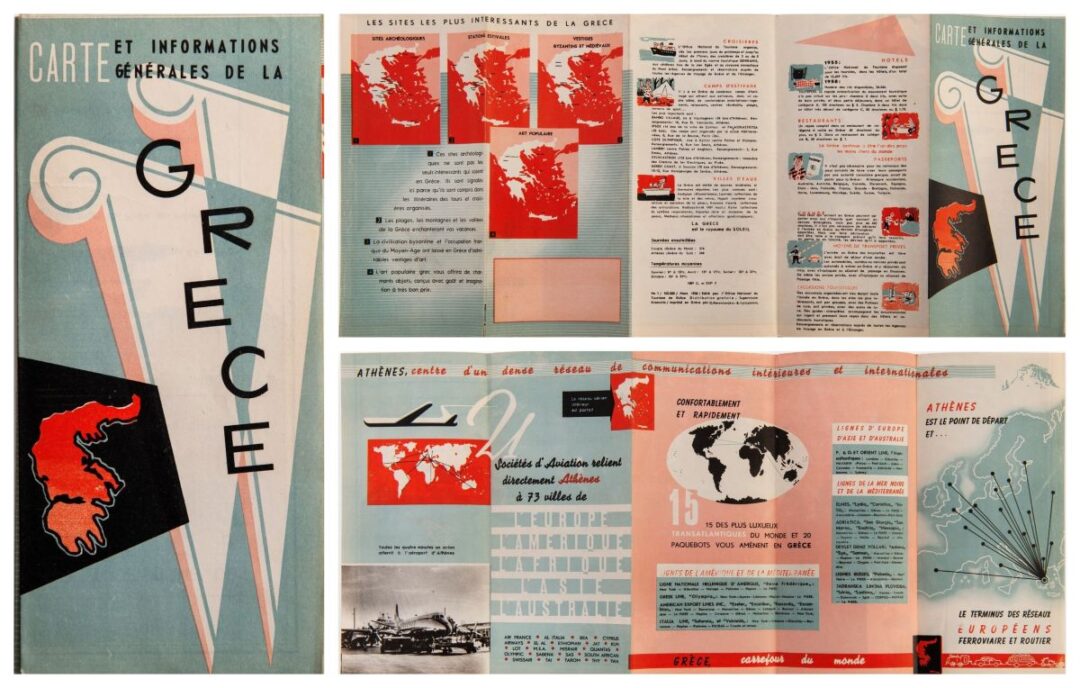

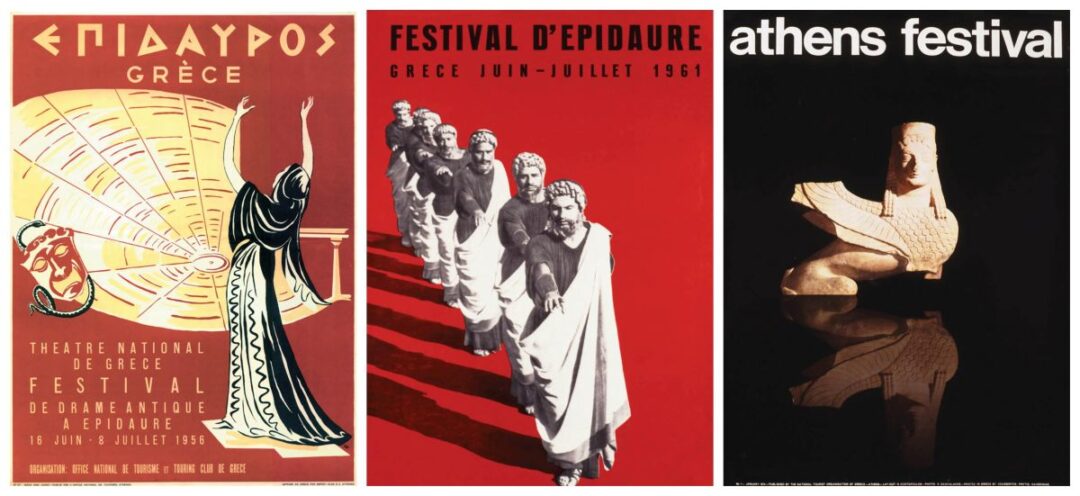

‘Imagining Greece‘ is an evolving research-based exhibition that explores how social, political, and cultural forces have shaped Greece’s image as a tourist destination. The exhibition brings together a rich diversity of archival materials on Greek tourism alongside first-hand accounts, presenting them on a single platform for the first time. It reveals the complex interplay of vision, ambitions, and expectations of those who established Greece as one of the world’s most beloved destinations and shaped the image of the idyllic Greek summer. Over the course of these five decades, the conditions for the development of the Greek tourism industry were shaped through state policies and private initiatives, which at times functioned complementarily and at others antagonistically. In the early postwar decades, the state assumed a dominant role through the newly established Greek National Tourism Organisation (GNTO, 1951), which implemented a remarkably broad and multidimensional programme of tourism reconstruction. This included the formation of the institutional framework for regulating the market, the promotion of the country’s image abroad, the renovation of existing and the construction of new leisure infrastructure and facilities, the upgrading of archaeological sites, the modernisation and densification of transport networks, the establishment of festivals, cultural events, and local celebrations, and the broader cultivation of tourism awareness as a tool for revitalising the Greek periphery.

Spearheaded by the ‘XENIA’ programme, the GNTO embarked on an unprecedented, large-scale, and innovative —considering the capacities of the time— production of mostly in-house and self-managed projects, such as hotels, motels, tourist pavilions, roadside stations, car camps, border posts, organized beaches, marinas, and more, alongside the regulation of excursion frameworks and the cruise market. The objective was to establish modern standards for tourism infrastructure and services, which private actors —who entered the field relatively early— would adopt, though without necessarily being bound by the guidelines set forth by the state.

By the end of the period under examination, the GNTO had effectively concluded this phase of its activity with an equally ambitious programme aimed at showcasing Greece’s vernacular architecture through the retrofitting of traditional mansions to guesthouses, thereby transitioning into a more strategic and managerial role. Our exhibition celebrates the cherished legacy of these formative decades, during which the founding mythology of the Greek summer first began to take shape through early efforts at strategic planning.

What aspects of the Greek experience does “Imagining Greece” highlight for potential or past travelers? Can you tell us more on the underlying concept of the “voyage immobile par excellence”?

The exhibition emulates a visitor’s journey from fantasizing about Greece, then travelling and discovering the country to remembering what is left of the Greek holiday. How do these visitors perceive Greece? What pictures and expectations inspire their journey? How does their presence influence Greek society? In what ways do they transition from mere tourists to catalysts of modernity, shaping the local economy and culture? As they travel across the islands and mainland, what do they discover? How does the country’s ancient heritage resonate with the spirit of the times? And what do they remember of their adventures? Is it the keepsakes they collect, the breathtaking landscapes etched in their memories, or the people they meet along the way? ‘Imagining Greece’ explores these questions and more, bringing the traveler’s experience to life through a captivating photographic and audiovisual collection spanning five decades.

The expansion of tourism has long been intertwined with the proliferation of travel literature and, from the 1960s onward, the rise of the travel documentary. These narrative forms extend beyond guiding prospective travelers in planning or navigating their journeys. Instead, they also contribute to the enduring and increasingly popular tradition of armchair travel — a form of imaginative escape from the routines of everyday life, mediated through text, photography, and moving images.

In recent years, technological advancements and the growth of the digital humanities have transformed armchair tourism into a distinct and dynamic field, both as an entrepreneurial venture and a mode of artistic expression. Freed from the constraints of physical mobility — whether economic, logistical, or temporal — this type of tourism offers the pleasures of discovery and immersion without the necessity of travel.

Our exhibition draws upon this idea of the quasi-journey to Greece — not only as a tangible geographical space but also as a site of memory, imagination, and cultural projection. Through a curated selection of digital exhibits spanning approximately five decades, we chart the evolution of tourism and its visual and experiential narratives.

What political, social, and cultural forces have shaped the global perception and image of Greece as an ideal place to visit? What would you say were the major turning points in the modern history of Greek tourism?

Since the end of the Second World war, it’s possible to observe the establishment of an integral part of Greece’s distinctive tourism ‘brand’- cultural tourism grounded in a widely shared appreciation of Greece’s ancient past and its myriad cultural legacies. The strength of these associations would play a major role in sustaining the remarkable growth of the Greek tourism industry for the remainder of the twentieth century and beyond. Innovations in air travel, package holidays and the popular use of the car however revolutionised the market ushering in a period of mass tourism, with Greece marketing itself as a land of ‘sun, sea and sand’ to foreign audiences. All of these were happening as the country was modernizing its infrastructure, upgrading the road network and, more broadly, creating new opportunities to experience Greece’s unspoiled landscapes and historical sites through newly established leisure facilities that adhered to international standards while highlighting local architectural features.

Aside from the GNTO, international tour operators were instrumental in introducing Greece to the wider world and attracting more visitors. Their contribution remains largely undocumented in recent scholarship. We hope that, as our exhibition evolves, further information on this subject will become available to the general public. Equally important, though less well known, was the critical role played by various clubs and organizations, such as the Hellenic Touring Club and the Automobile and Touring Club of Greece, which supported the GNTO in the micro-management of various aspects of tourism development. These ranged from the organization of festivals and local feasts, to the promotion of water sports, the operation of campsites, the publication of travel guidebooks and updated maps, and the maintenance of road and directional signage. Their micro-histories are closely interwoven with the evolution of tourism in Greece, particularly the rise of domestic tourism during the 1960s and 1970s. Another milestone, albeit not in a strictly chronological sense, was the involvement of the private sector —particularly banks— in the tourism industry. This led to a significant increase in serious stakeholders within the sector, marked by the arrival of international hotel chains in Greece and the emergence of domestic hotel groups, some of which remain active to this day.

How did the growth of tourism influence Greek society and its economy during the post-war and Cold War eras? It is often said that tourism is Greece’s ‘heavy industry’. Do you agree with that take and what are its implications?

Tourism has constantly been upward trending in the last decades. It started in 1950 with 33,000 visitors, skyrocketed to 5.271.000 in 1980 to reach 36 million tourists in 2024. Until 1990, Greece’s development in the tourism sector was the fastest in Europe. Tourism has become the country’s heavy industry with a contribution of almost 25 percent to GDP and employing more than 400.000 Greeks.Even in 1948 in the midst of the Greek civil war, the American Mission had identified tourism as a major source of foreign currency and an avenue for the country’s economic reconstruction. The implications of an over reliance on the Greek tourism product, is Greece’s vulnerability to the massive influx of tourists and how that affects the quality of life of the local population, and threatens the country’s landscape and traditions.

Greece’s destination branding has been based on “Sun, Sea & Sand” triptych as well on ancient sites and the country as the “Cradle of Western Civilization”. Do you see any other branding options opening up in the future?

In an efforts to grow their country’s tourism sector, Greek stakeholders have grappled with the same conceptual schism between an imagined Hellas (a ‘romanticized spectre of a lost civilization’ built on ‘the desired relics of material culture’) that had become deeply embedded in the foreign imagination during the 19th century, and a modern Greece, at once a ‘geographical space that hosted the material remnants of Hellas’ while being ‘inferior to it’ and a desirable destination for sun-worshipping travelers seeking respite from modernity. The demand for the ‘Greek summer’ remains unabated. Extending the tourist season has been a long-standing goal for the Greek tourist industry and since the 1970s Greece had branded itself as the land of all seasons but only recently has managed to achieve that. In a pursuit for a more sustainable tourism, there are calls for diversification of the tourist product, with alternative activities beyond the usual ‘sun and sea that will make Greece an all-year round European destination.

Your current research project deals with the role of tourism and mobility in the construction of a Southern European identity. What are the components of a Southern European Identity, and how do tourism and mobility interplay with other factors that shape it?

The countries of Southern Europe are, for the most part, also Mediterranean countries, and this characteristic has significantly shaped their identities for centuries. Around the life-giving waters of this enclosed sea —Mare Nostrum, as the Romans called it— national identities gradually took shape, united by a common thread: the sea as an open route for trade, a bridge for cultural exchange, and, at times, a means of conquest through brute force. Southern European identity, as an intellectual construct, is by its very nature inextricably linked to the rich and densely layered cultural geography of the Mediterranean sunbelt, whose origins are lost in the depths of historical time. Enduring elements of the mythology of the Mediterranean have consistently included antiquities, the sun, and the coastlines —sometimes gentle, at other times dramatic— that have been immortalized in every form of art.

For the modern Greek state, the formation of its national identity is likewise inextricably linked to the emergence of modernity in the 19th and 20th centuries, as expressed through touring (e.g., the Grand Tour) and, later, tourism respectively. The geographical and cultural mobility of cosmopolitan Europeans and Americans —bourgeois merchants, scientists, and artists from the elites of the 19th century and the interwar period, who, through their travels, paid homage to the ancestral civilization of ancient Greece— played a significant role in shaping the conditions and terms under which Greeks were reconstituted as a nation, a people, a country, and an idea(l). This same phenomenon also influenced the image of the West itself, whose model the Greeks continuously measured themselves against — while always casting a sidelong glance towards the alluring East.

In the postwar period, the Greek version of Southern European identity was significantly reshaped by tourism, a dynamic phenomenon that fueled social, economic, and cultural transformations in both urban centres and the periphery. The vast mobility generated by the massification of tourism established holidays as a democratic right to leisure time — not only for Northern Europeans, whose ‘exodus’ to the sun-drenched South and the Greek archipelago was experienced as restorative, but also for Greeks themselves, for whom contact with the traveler’s ‘otherness’ became a form of education. In the case of Greece, as in other southern countries, the redefinition of national identity through tourism was filtered via the process of modernization. More specifically, the Greek state was restructured institutionally, politically, economically, socially, and culturally, with the aim of aligning the Greek standard ever more closely with that of Europe. Greece reinvents itself in order to promote its image both abroad and at home — a process broadly analogous to that of the 19th century, when the Western gaze largely shaped the way in which modern Greeks wished to view themselves and their future.

*Interview to: Ioulia Livaditi

Read more from Greek News Agenda

TAGS: DESIGN | EXHIBITION | MODERN GREEK HISTORY | TOURISM