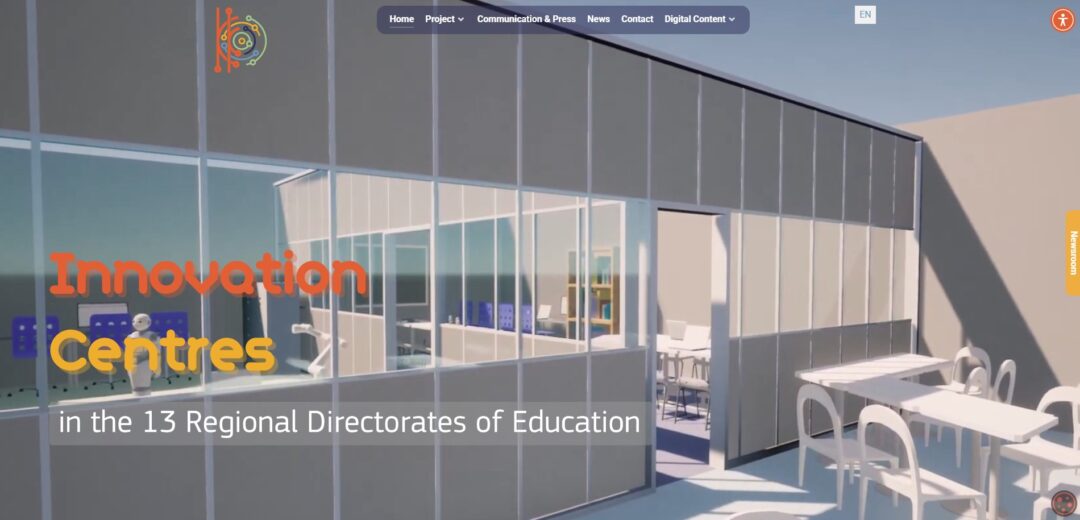

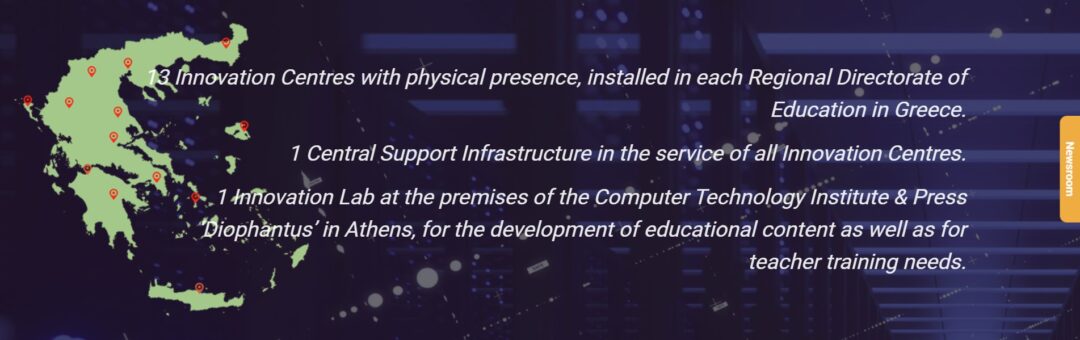

The new Innovation Center of Epirus was recently inaugurated in Ioannina by the Minister of Education, Religious Affairs and Sports, Sofia Zacharaki, and was also visited in the afternoon by the Prime Minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis. The Epirus Innovation Center is housed in the Kato Marmara Municipal Primary School of Ioannina and is part of the nationwide network of 13 Innovation Centers, which are being established in every Regional Directorate of Education in the country and are scientifically and pedagogically supported by the Computer Technology Institute and Press (CTI) “Diophantus.” The operation of the Innovation Centers is being implemented within the framework of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan – Greece 2.0, funded by the European Union (NextGenerationEU).

Innovation Centres constitute a knowledge ecosystem that integrates and links the school community, the local community, research institutions, universities and local businesses, while connecting with similar educational ecosystems in Europe and elsewhere in the world. Innovation Centres are purpose-built, high-quality environments for STEM learning, green growth and innovation promotion in general. Each lab can be designed to support multiple topics and curriculum modules to meet the unique educational needs of each community.

They aim to have both a virtual format to support remote schools and districts, and a physical presence at a specific site to be visited by stakeholders. At the same time, one Innovation Lab will be developed in the premises of the implementing institution for the needs of designing the educational material and the training of the teachers who will staff the Innovation Centres.

In detail, the scope of the project includes the following five (5) main pillars:

- Educational Programmes: For all educational programmes, detailed scenarios and educational material is being developed, covering the teaching of each subject, while at the same time manuals are being compiled for students and teachers.

- Supply and installation of technological/network equipment (hardware/software) to enable the implementation of these specific educational programmes.

- Architectural design of Innovation Centres’ premises: The supply and installation of office-hall equipment and other interior design works is being carried out to serve the single identity among all ICs, with a pleasant and playful environment that attracts visitors. The exterior premises of each IC can also be used for the implementation of educational scenarios!

- Training of teachers and, in general, of the personnel that will staff Innovation Centres, so that they acquire the necessary knowledge and skills to carry out the task of disseminating knowledge to both the teachers who will visit the ICs and their students.

- Services: Production of educational modules, piloting & technical support services, project coordination and management.

(Source: https://www.cti.gr/en/homepage/)

During the inauguration, students, teachers, and education officials had the opportunity to actively interact and experiment with modern technological applications as part of experiential and collaborative activities that highlight the Center’s pedagogical orientation.

In her speech, the Minister of Education, Religious Affairs and Sports, Sofia Zacharaki, emphasized that the Epirus Innovation Center is a true hub of learning, collaboration and coordination, serving the school of tomorrow. “Today we are here in Ioannina, at the second Innovation Center we are inaugurating outside Athens, as part of the Ministry of Education’s cooperation with CTI ‘Diophantus’ and with funding from the Recovery Fund. This is an important opportunity for all children, wherever they are and wherever they attend school, to have equal access to meaningful learning experiences. At this Center, students will come into contact with technology and science through applications of augmented reality, robotics and modern technological tools, while at the same time becoming familiar with important elements from different scientific and professional fields. Their teachers – technologists, physicists, chemists and others – will have the opportunity to prepare them through educational scenarios and, upon returning to school, to put into practice what they have worked on here. I am particularly pleased that the institution of Innovation Centers is being strengthened, and I warmly thank the Municipality for providing the space, the Regional Directorate of Education and all the education officials who contribute to establishing this new institution. I reiterate the steady emphasis we place on broadening the range of opportunities and ensuring equal opportunities for all children, in every region of the country”, stressed the Minister.

(Source: minedu.gov.gr/)

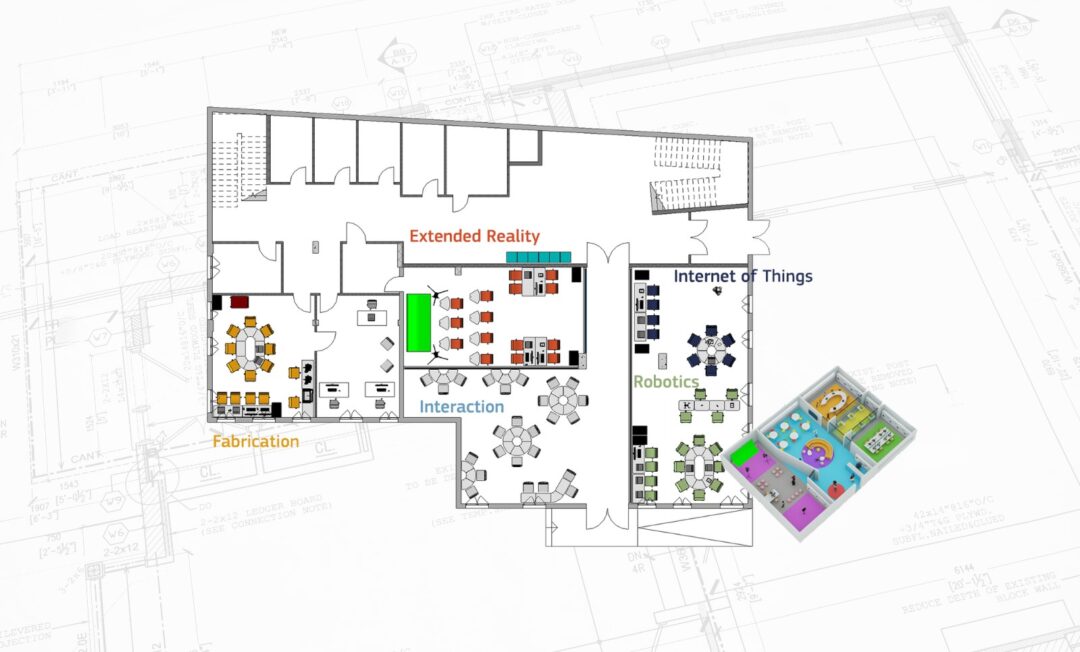

Every Innovation Centre includes 5 units:

Extended Reality (XR) technologies, including Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR). These technologies enhance education by creating immersive and interactive learning experiences. Equipped with VR/AR devices, computers, and specialized software, the XR space allows students to actively engage with digital environments, fostering creativity, collaboration, and exploration of advanced technologies. It also functions as a green screen room and can serve as a virtual collaboration studio, enabling live interaction between Innovation Centres in different regions.

In the Internet of Things learning space, students explore artificial intelligence, machine learning, big data, and the Internet of Things through hands-on activities. They develop age-appropriate programming and operational skills, design software, analyze data, and practice algorithm-based decision-making. This integrated approach strengthens critical thinking and problem-solving skills for the digital age. The space also includes dedicated laptop and tablet workstations for tasks such as system design, video editing, and programming.

In the Robotics learning space, students engage with science, technology, engineering, and mathematics through hands-on activities using robotic technologies. With tools such as robotic arms, social robots, Arduino and Raspberry Pi boards, sensors, and STEM kits, they explore programming, design, and real-world applications. This dynamic environment fosters critical thinking, problem-solving, collaboration, and prepares students for today’s technological era.

The Fabrication learning space blends digital and hands-on creation, following the model of MIT’s FabLab network. Equipped with 3D printers, laser and vinyl cutters, and a 3D scanner, it enables students to transform digital designs into physical objects. Alongside digital tools, traditional hand and electric tools support practical skill development. In this versatile environment, students enhance their creativity while building programming, design, and crafting skills.

The Innovation Centre includes a dedicated meeting and presentation area that also functions as a welcoming reception space. Equipped with interactive whiteboards, advanced audio systems, and teleconferencing tools, it supports high-quality presentations, events, and student project showcases. Designed for flexibility and active participation, the space fosters interaction while adapting to evolving needs.

(Source: https://ic.cti.gr/en/about/laboratories.html)

TAGS: EDUCATION | INNOVATION | TECHNOLOGY