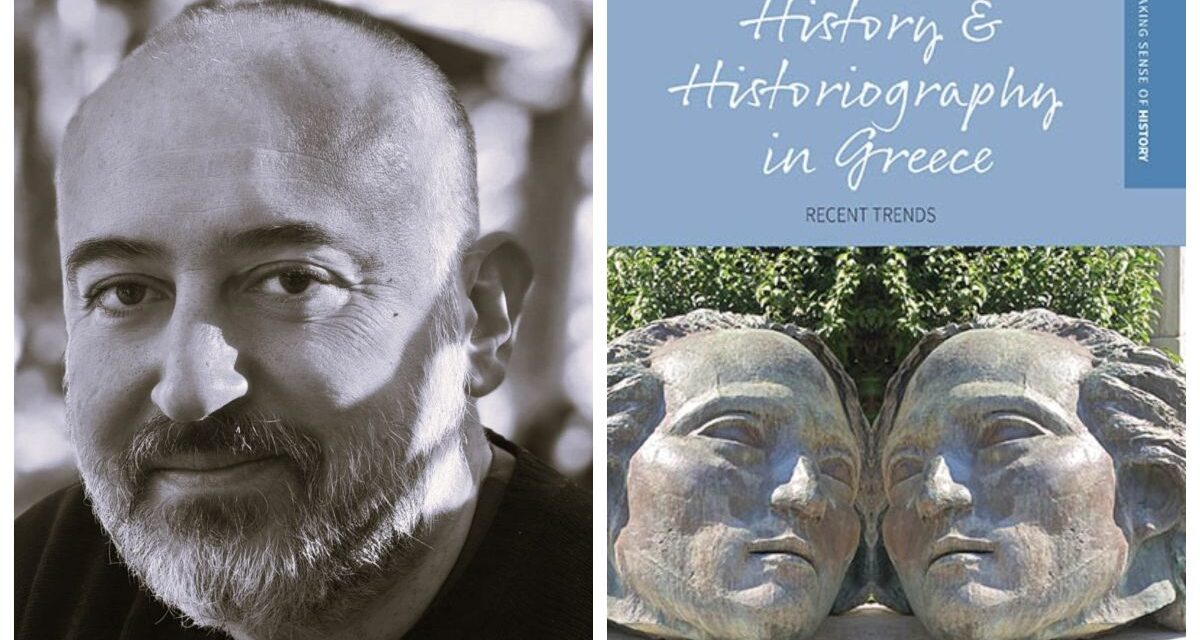

Nikos Christofis, Assistant Professor of International Cultural Relations at the Department of Language and Intercultural Studies at the University of Thessaly, was interviewed by Rethinking Greece* on the occasion of the publication of the collective volume History and Historiography in Greece :Recent Trends, which he edited. Professor Christofis examines how Greek historiography has evolved—from nation-building narratives to transnational and interdisciplinary approaches. He highlights the impact of the Metapolitefsi period, the rise of gender and memory studies, and the growing internationalization of the field and interconnection between historiography and national identity. Finally, he emphasizes the importance of transnational and comparative frameworks in decentering Greek exceptionalism and aligning modern Greek historiography with broader international scholarly trends. Despite challenges such as language barriers and limited funding, Greek historiography is increasingly dialoguing with global currents.

What are the central aims and motivations behind this volume on history and historiography in Greece?

The idea for this collection originated at the 26th Modern Greek Studies Association Symposium, held in Sacramento, California, on 7–9 November 2019. The symposium showcased a wide range of topics and high-quality research on various aspects of modern Greek history, which brought to my attention the pressing need for an updated volume on Greek historiography. The vision for this book became even clearer when I began teaching the course “Theories of History and Historiography” in the “Public History” postgraduate program at the Hellenic Open University, where I serve as an adjunct lecturer. It became evident that a comprehensive volume addressing the key themes explored in that course could serve as a valuable resource for both graduate and postgraduate students.

Against this background, the project aspires to serve as a contemporary companion to the monumental two-volume proceedings of the Fourth International History Congress, published by the Institute for Neohellenic Research in 2002, which was entirely dedicated to Greek historiography. The book traces the evolution of Greek historical scholarship by reviewing the ideas, methods, and schools of history shaping the field, while, at the same time, places Greek historiography in an international context by checking how these developments correspond with international trends and their rate of development alongside global shifts in scholarship.

How did the establishment of the Greek state in 1830 influence the development of historical writing in Greece? What was the “national mission” of the University of Athens and its historians in the early decades of the Greek state?

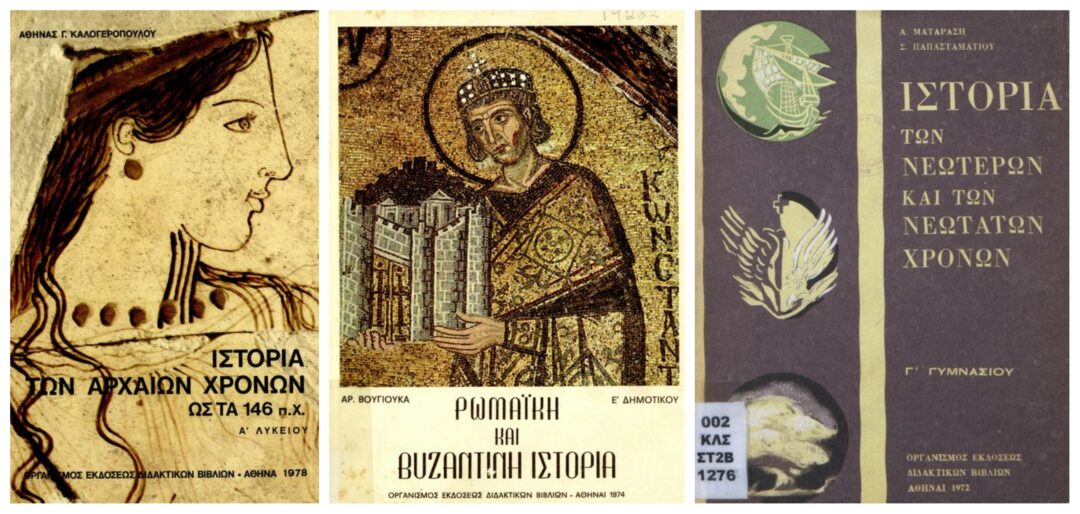

As in many parts of the world, the development of the historical sciences in Greece was closely tied to the formation of the modern Greek nation-state in 1830. From the outset, historians made significant efforts to conceptualize a unified national state with a continuous historical narrative and a shared national consciousness, enabling the Greek people to claim a legitimized past stretching from antiquity to the present.

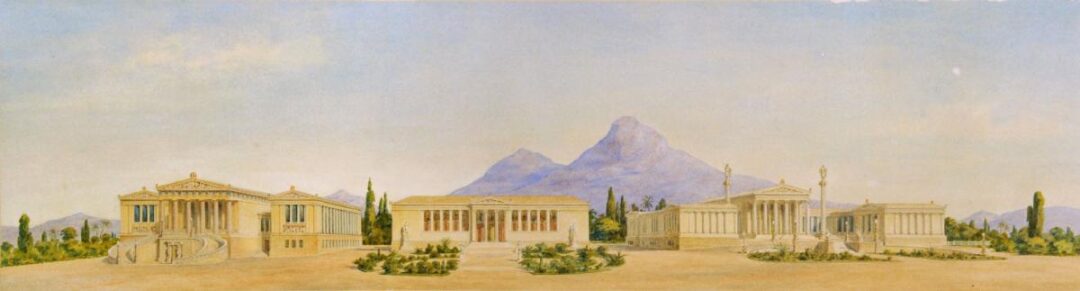

Following the Greek Revolution and the establishment of the independent state, history proved instrumental in achieving the broader goal of national consolidation. Greek antiquity and the Byzantine period were especially emphasized as sources of prestige and cultural legitimacy, particularly through the influential writings of figures such as Constantine Paparrigopoulos and Spyridon Zambelios.

In this context, the University of Athens—founded in 1837—played a central role in shaping the historical sciences in Greece for more than eight decades. It not only supplied personnel for the emerging state apparatus but also helped construct and disseminate a national historical narrative. The university’s symbolic authority was pivotal in promoting the Megali Idea, the dominant irredentist nationalist ideology of the time, and in advancing the cause of Hellenism, particularly within the territories still under Ottoman rule. Language, religion, and especially history were employed as key unifying elements, intended to forge connections between the subjects of the new Hellenic Kingdom and the Greek-speaking Orthodox populations of the Ottoman Empire.

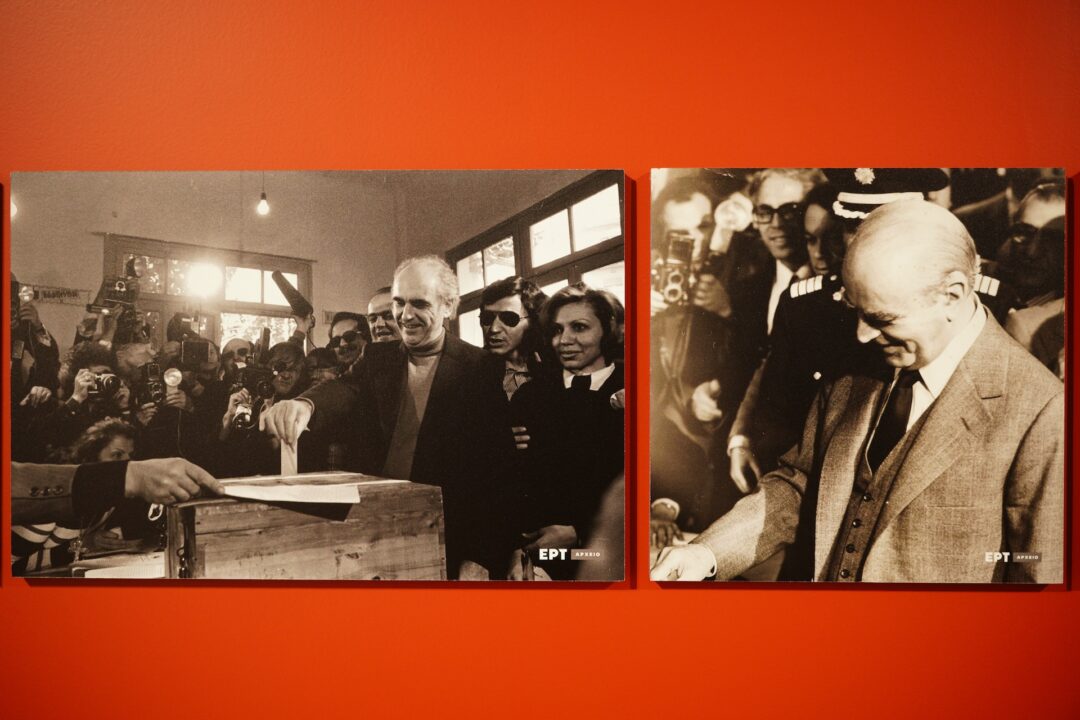

How did the Metapolitefsi period (post-1974) impact Greek historiography and introduce new approaches?

The Metapolitefsi—the period following the fall of the Colonels’ dictatorship in 1974—marked the beginning of a gradual yet profound sociopolitical transformation in Greece. In the realm of historiography, it sparked a significant “explosion,” evident in the structural evolution and expansion of the professional historical community. Many Greek historians who had sought refuge primarily in Europe during the dictatorship returned shortly thereafter, bringing with them fresh perspectives and revitalizing the field. Exposed to new intellectual currents and in dialogue with international scholars, these returning historians introduced critical questions and approaches that enabled the integration of Greek history into broader global narratives. To a considerable extent, this generation reshaped the practice of historical writing in Greece, with many assuming influential roles within the emerging institutional landscape.

What roles have Gender History, Biography & Memory Studies played in shaping recent historiographical developments in Greece? What significance do these approaches hold within the broader field of Greek historical studies?”

Gender History, Biography, and Memory Studies emerged within the broader intellectual movement known as the New History, which gained prominence across various national historiographical traditions. Broadly speaking, this movement represented an epistemological shift from viewing history as a fixed set of facts to understanding it as a field of inquiry and interpretation. The New History critically challenged both the positivist illusions of traditional historiography and the dominant nationalist narratives propagated by established academic institutions. Instead, it emphasized the analysis of economic and social structures, prioritized interpretation over description, and employed impersonal analytical categories. In essence, history began to be approached as a social science.

Although the roots of this paradigm shift in Greek historiography can be traced to earlier decades, it crystallized during the late 1970s and 1980s. These new approaches have offered alternative perspectives on the past, particularly by highlighting the experiences of marginalized groups and questioning established historical narratives. Through the lenses of gender history, biography, and memory studies, scholars are now able to interrogate social structures, analyze gendered discourses, explore individual lives, personalize history, and examine collective memory and cultural practices. Collectively, these fields have made Greek historiography more inclusive, dynamic, and nuanced.

In what ways have comparative and transnational frameworks impacted Greek historiography, and how have they contributed to rethinking national narratives or methodological approaches?

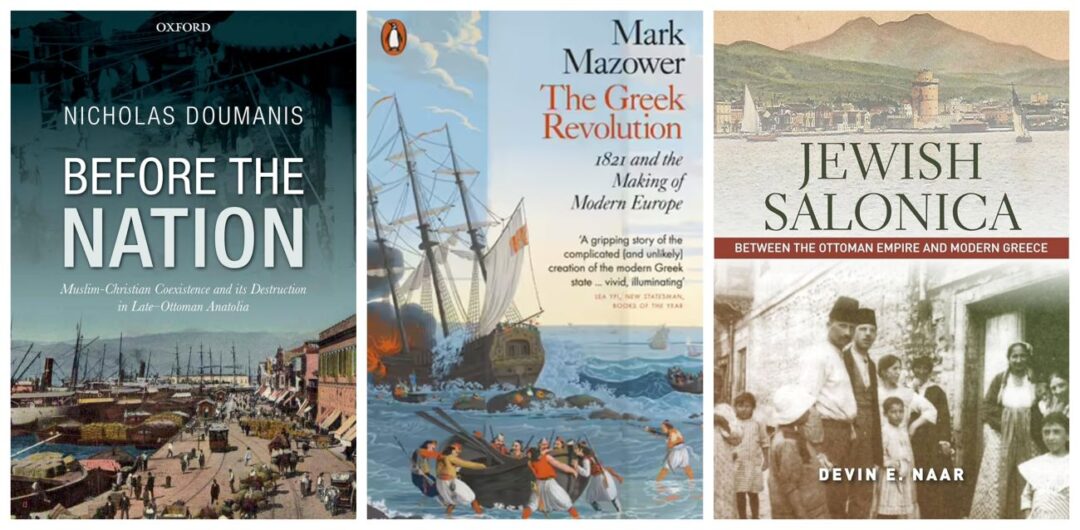

Comparative and transnational frameworks have profoundly reshaped Greek historiography – transnational more than comparative history, I believe – by challenging the traditional nation-centered narratives that emphasized Greece’s exceptionalism (e.g. the example of the Greek Revolution) and linear national development. These approaches situate Greek history within broader regional, European, and global contexts, revealing the interconnectedness of Greek experiences with those of the Ottoman Empire, the Balkans, and the Mediterranean. By highlighting cross-border flows of people, ideas, and goods, they have decentered, or at least they try to do so, the nation-state as the sole unit of analysis and introduced interdisciplinary methods that incorporate social, cultural, and economic perspectives. This has led to more pluralistic histories that include minority voices, diasporic influences, and transnational actors, thereby complicating nationalist myths and encouraging critical reflection on the construction of Greek identity. Consequently, Greek historiography has become more dialogic and internationally engaged, enriching both its methodological toolkit and its understanding of national narratives as contingent and multifaceted rather than fixed and exceptional.

In your view, how do historiography and national identity intersect, and in what ways do they shape or influence one another?

Historiography and national identity are deeply interconnected, as the writing of history often serves as a crucial tool in constructing and legitimizing the nation. Through selective emphasis on certain events, figures, and cultural achievements—while often omitting uncomfortable or divisive aspects—historiography helps forge a shared narrative that binds individuals into a collective identity. This narrative is further reinforced through educational curricula, public monuments, national holidays, and museums, all of which draw from dominant historical interpretations to cultivate a sense of belonging and continuity. Conversely, national identity also shapes historiographical agendas, as state institutions, political ideologies, and cultural priorities influence which histories are preserved, taught, or suppressed. In more recent decades, however, the emergence of new historiographical approaches—such as gender history, memory studies, and postcolonial critique—has begun to challenge traditional nationalist narratives, offering more inclusive and critical perspectives that reflect the diversity and complexity of the past. As a result, the relationship between historiography and national identity remains dynamic, with each continually shaping and reshaping the other in response to evolving political, social, and intellectual contexts.

What do you identify as the current trends and key challenges in the study of modern Greek history? To what extent does the Greek academic community engage with broader international developments in historiography?

Current trends in the study of modern Greek history reveal a significant shift away from traditional nation-centric narratives toward more nuanced, transnational, and interdisciplinary approaches. Greek historians are increasingly situating Greece within broader Ottoman, Balkan, and Mediterranean, but also global contexts, exploring shared histories and cross-border influences that challenge earlier linear and exceptionalist national stories. This shift is complemented by the incorporation of gender studies, social history, and cultural analysis, which have expanded the field beyond elite-focused perspectives to include marginalized voices and diverse experiences.

However, the field faces key challenges, notably a degree of insularity due to the predominance of Greek-language scholarship and limited translations into English – although all the more the new generation of Greek historians publish in other languages – which restrict its international visibility and integration. Economic difficulties have further compounded these issues by reducing funding for research and causing a brain drain of promising scholars seeking opportunities abroad. Despite these obstacles, the Greek academic community is increasingly engaging with global historiographical developments through participation in international research networks, publication in global journals, and interdisciplinary initiatives that align with contemporary methodological trends. Prestigious European grants and collaborations, such as those involving the Institute for Mediterranean Studies, demonstrate growing recognition of Greek scholarship internationally. Thus, while resource limitations and language barriers remain significant challenges, the adoption of comparative and transnational frameworks alongside efforts to foster global academic dialogue signal a promising evolution in modern Greek historiography.

*Interview to Ioulia Livaditi

Read also from Greek News Agenda

- Rethinking Greece | Nicholas Doumanis on the last century of Greek history: Greeks are resilient and resourceful

- Rethinking Greece: Kostas Kostis on the War for Greek Independence and the creation of the modern Greek state

- Rethinking Greece: Henriette-Rika Benveniste on the history of Greek Jewish communities

- Rethinking Greece: Dimitra Vassiliadou on the history of emotions, sexuality and Greek historiography

TAGS: GREEK WAR OF INDEPENDENCE | MODERN GREEK HISTORY | MODERN GREEK STUDIES | NEW HISTORY