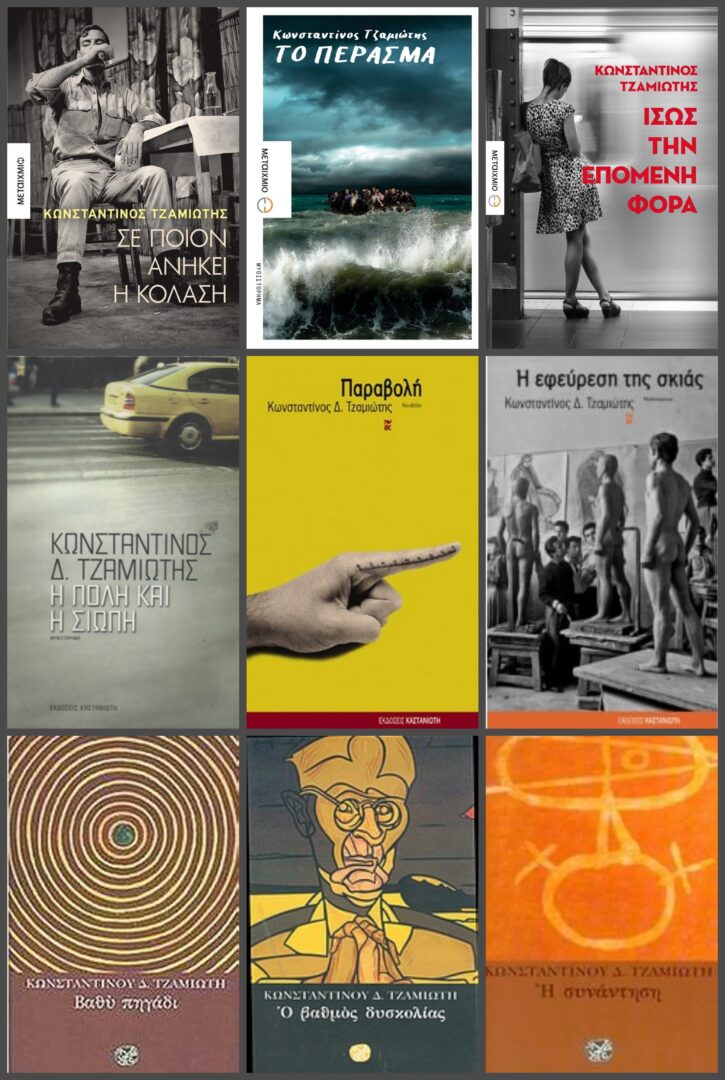

Konstantinos Tzamiotis was born in 1970 in Larissa. He studied cinema. He lives in Athens. His books include The City and Silence (2013), The Invention of Shadow (2008), Parabola (2006), The Degree of Difficulty (2005), Deep Well (2003), The Encounter (2002). His short stories have been published in magazines, anthologies and collective editions. His first play, Neutral Zone, won the State Prize for Emerging Playwright. His play An Extremely Simple Work was included in the European Theatre Anthology.

His texts and articles on cultural and contemporary art issues have been translated into several languages. The following novels are published by Metaixmio: The Passage (2016 – Athens Prize for Literature), translated in France by Actes Sud, Maybe Next Time (2017), and To Whom Hell Belongs (2019), as well as the children’s book The State of Shoes and Barefoot Hippolytus.

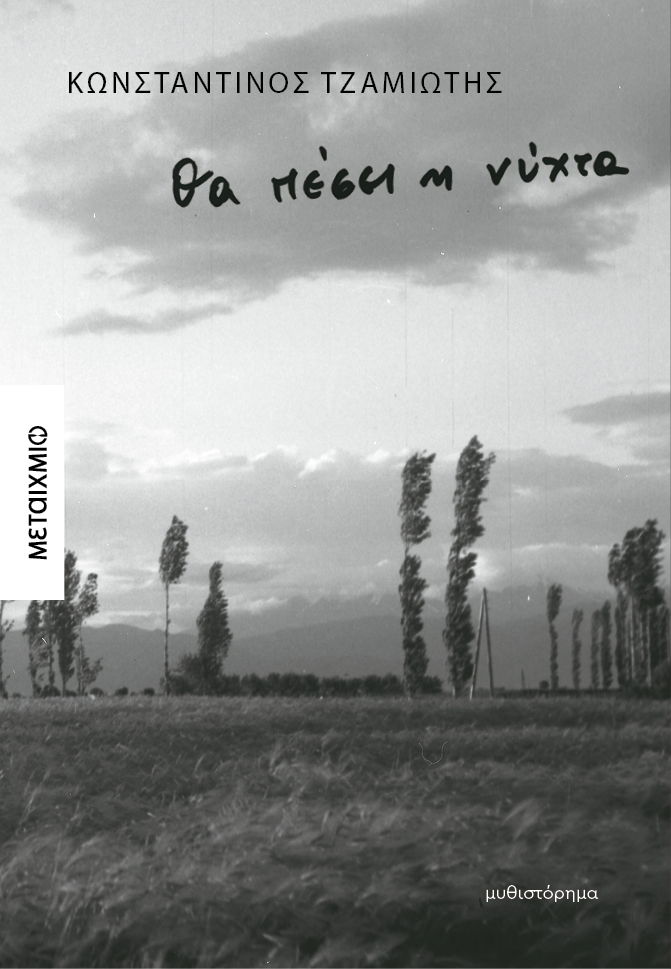

Your latest writing venture Θα πέσει η νύχτα [Τhe Night Will Fall] (Μetaichmio, 2025) is “a family saga, a coming-of-age story, a testimony of a collective lethargy that lasts for almost a century, a somewhat detective story, along with loves and deaths, which intertwine to create a universe that is sometimes envious and sometimes bleak”. Tell us a few things about the book.

It talks about life, our own life. Life that has joys, sorrows, triumphs, failures, compromises, rebellions, no matter who we are. It speaks of individual responsibility and collective apathy, of the bravery of the few and the cowardice of the many. It also speaks of the need to remain human, even though this is not in one’s best interests these days. In short, it speaks of the adventure of life in our world.

From The Encounter in 2002 to The Night Will Fall more than 20 years later, what has changed and what has remained the same in your books? Are there recurrent points of reference in your writings?

It happens with all writers and I’m probably no exception. Indeed, in my books one can discern certain patterns, some obsessions if you like. Perhaps they have something to do with my aversion to any kind of authority. I cannot be absolutely sure. My characters, however, despite the antinomies and contradictions that govern their lives, reach in one way or another a critical point of self-consciousness, beyond which hesitations become superfluous. And they decide to go against the tide even if such a decision may mean their own extinction. They behave like salmons, the fish, going against the flow of life. In other words, they are tragic persons, since bears will always be waiting to satiate their hunger at the top of any waterfall they have to go over.

The personal lives of your heroes are inextricably linked to the public sphere. Where does the personal meet the collective in your work?

We all maintain a secret world at our core. A personal universe made of values, cheapness, fears, inhibitions, desires, darkness and light. The point is, we are not alone. We are far too many for that. And one must find ways to discern, cope with or reconcile with the distinct time of others. I would venture to say that the stories I write are nothing more than alchemical quests, a blind search for what is the strongest glue so that someone who doesn’t want to lose themselves tries to find ways to do things with others.

More generally, how does literature relate its surrounding social environment? Could literature be used to imagine what could be radically different realities?

I reckon that only fiction can do that. Not because it denies the real world, but precisely because it offers possibilities – in other words – ways of better understanding and, if possible, expanding reality. Without literature we would look like someone standing with their face stuck to a wall, believing that this is their allotted space while behind their back there lies a vast room.

In your books, fiction is inseparably tied with history and the past? Where does the various micro-stories that appear in your novels meet the History of the world?

It’s my firm belief that if you don’t know where you come from, you won’t know where to go next. Yet, knowing your roots can often be extremely complicated if not painful. That’s why sweet revisionism and even sweeter nostalgia prevail these days. Most of us Westerners have lived a rather easy life compared to previous generations. This has clouded and narrowed our horizons. It has made us believe that History is over and that from now on, only constant progress awaits us. But History was, is and will always be here. Especially nowadays we all understand what that means.

What about language? What role does language play in your work?

Crucial. Just a small remark. The language I use is not necessarily my own. It’s the language of the characters that parade through my stories. And often it’s a language that contradicts or tries to invalidate my own speech. But that’s the price of telling stories in a simple and moving way.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE