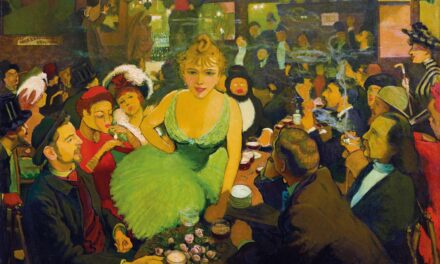

Renowned for his unique fusion of realism and dreamlike surrealism, Dimitris Anastasiou stands out as a significant figure in contemporary Greek art. Whether through paintings, polyptychs, or graphic novels, Anastasiou’s work consistently evokes an atmosphere of cinematic stillness, existential depth and psychological complexity.

In his work every detail is rendered with photographic clarity. His compositions depict everyday scenes, stranded urban interiors, anonymous portraits, mundane interiors, evoking feelings of isolation, alienation, unanswered questions and unsettling ambiguity.

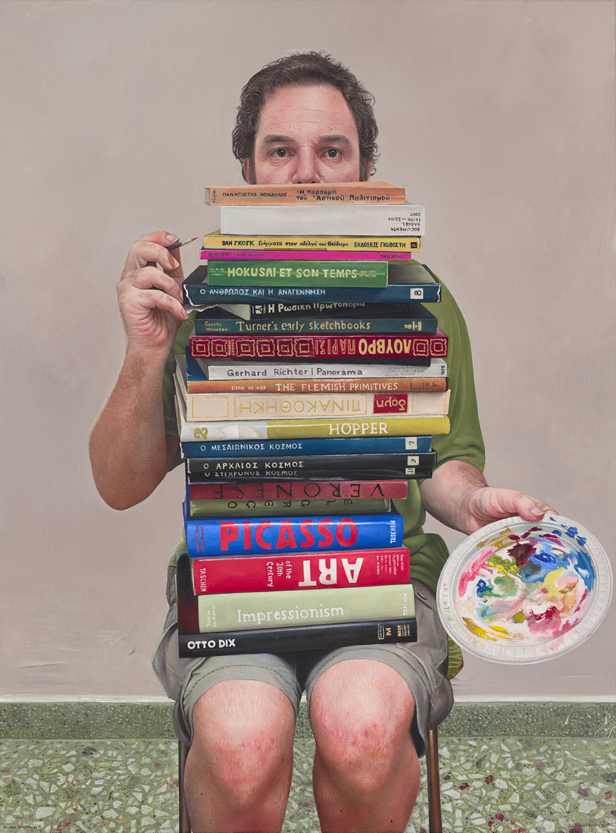

By reframing reality as a dreamscape, he invites viewers not only to see but to participate in the mystery. Anastasiou frequently inserts himself into his scenes, reminding the viewer of his presence as both spectator and participant. But, as he points out, even if he occasionally plays himself, he is still “playing roles, like an actor”.

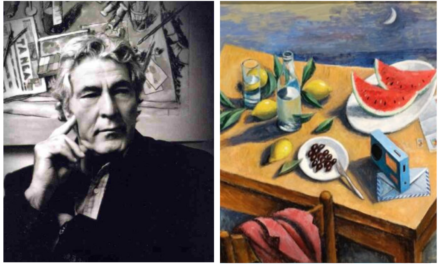

Dimitris Anastasiou was born in Athens in 1979. He studied painting at the Athens School of Fine Arts under professor Chronis Botsoglou. He has presented four solo shows and has participated in over 50 group exhibitions in Greece, Russia and Cyprus and in international art fairs in Greece, Spain, Switzerland and Germany. His graphic novel “A=-A’ is published in English by Jonathan Cape and in Greek by Kaleidoscope Publications. He has significantly contributed to the 27th Thessaloniki International Documentary Festival (2025) as the official posters of Festival bear his signature.

Greek News Agenda* spoke with Dimitris Anastasiou about his artistic language, his personal presence in art and the quiet power of concealment.

Your visual language is rooted in a form of illusory realism. What led you to this choice?

Our visual idiom, much like our spoken one; it isn’t something we consciously choose. We belong to it more than it belongs to us. As a student, I tried to paint like the great expressionists who moved me deeply. But I felt like as though I was pretending to be the painter I wished to be. Eventually, I came to terms with it; I let go of those foreign “languages” and began to study my own visual mother tongue.

That said, I do have another inherent tendency: to play with styles, to shift the tone of my painting, to borrow elements of art history, cinema, and comics. Yet, despite all these detours, I always return to the same starting and ending point: the realistic depiction of the world.

Your works depict everyday scenes. Yet, they feel evocative and layered. What themes are you exploring through this approach?

In dreams, even the most improbable things usually make sense; we might ask our grandmother, who passed away twenty years ago, if she has cooked; the bathroom moves between floors like an elevator; we find ourselves acting in the very movie we are watching on TV.

And while none of that strikes us as odd, something much simpler, an unexpected word or a light bulb that defies its switch, can suddenly shatter the dream completely. I often feel that everyday life as I paint it is the dream of someone who has just realized they are dreaming.

Your own presence in your works is striking. Why do you feel compelled to appear in your paintings? How autobiographical are they?

In a way, all painters create self-portraits, even when we paint other people. We use their form to convey our own vision of painting and life, our own concerns, our own likes and dislikes. The model is the means, not the end. That’s why I jokingly say that Kant would find us immoral.Paradoxically, though, the opposite is also true: when I paint myself, I am not being autobiographical. I am playing roles, like an actor, even if, occasionally, I play myself.

My works are experiential, not autobiographical. I say experiential because I mostly paint what I know and I mostly know what I have experienced. However, I try to remove any elements that I consider to be strictly personal, those elements that would interest only me or my loved ones. My artistic goal is to reach a common ground—not in terms of circumstances, but in terms of essence.

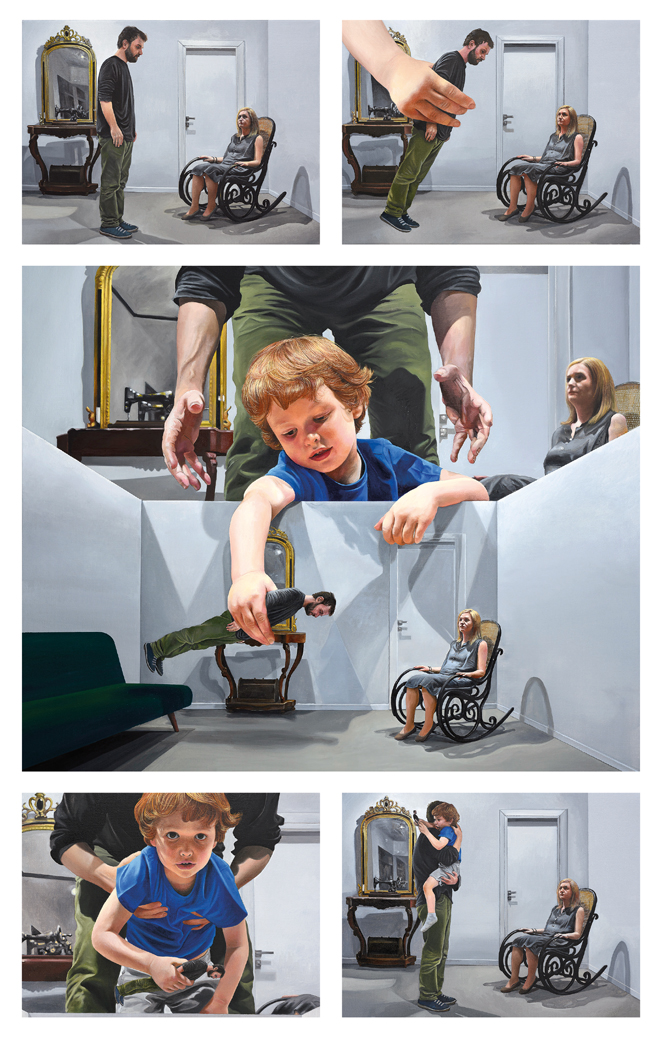

Your works feel like film frames. There is a strong sense that something came before and something is about to follow. What role does narrative play in your works?

When I paint, I create a static cinema, my own still movie. That’s why I consider directors like Roy Andersson, Robert Bresson, and David Lynch to be my true mentors in painting. I actually think of my paintings as the surviving frames of a film reel that caught fire, as scenes from a movie the viewer is invited to imagine.

And often, it’s more than just a feeling that something came before and something is about to follow as many of my works are structured as image sequences. Sometimes they take the form of wall-mounted polyptychs; other times, they resemble comic book pages—with or without text. Occasionally, they evolve into full graphic novels.

You have created three remarkable posters for this year’s Thessaloniki International Documentary Festival, where place and time play a key role. Can you tell us about them?

In the spirit of a documentary film festival, the three posters, like cinematic frames, tell a short story: the journey of a hero from the past to the future, from a simple and familiar world to a strange and frightening one, from loneliness to companionship. Each of the three images stands on its own, but together, they form a triptych.

In your view, does art conceal or reveal?

When I make the (conscious) decision to paint something, I simultaneously make the (less conscious) decision not to paint everything else. Reality is chaotic—I can’t control it. But, in art, I have the luxury of directing; I can play with light and shadow, spotlight what I want to highlight , making everything else disappear.

This is, of course, an arrangement, a fabrication, a constructed condition. But it’s not meant to deceive. It is a concealment aimed at some kind of revelation. Or, in Picasso’s words: “Art is a lie that helps us get closer to the truth.”

Of course, directing doesn’t mean absolute control. There will always be things that, no matter how much we push them into the background, reappear in the foreground —just as there are others that, no matter how much we illuminate them remain in the dark.

That is both frustrating and fascinating. If we could fully define or understand our work it would have nothing to reveal to us. We’d be self-sufficient initiates and preachers—revealing without being revealed. But as it stands, we move forward—dazzled and uncertain—hoping someone will come along to share the wonder with us.

*Interview by Dora Trogadi

TAGS: ARTS