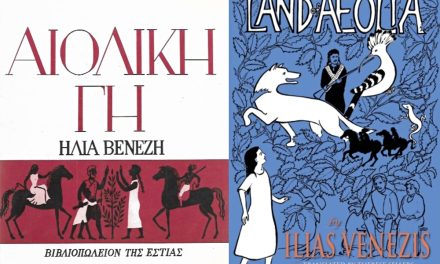

Maria Archimandriti was born in 1981. She has a degree in Balkan Studies and a specialization in marketing. Her poems have been published in various newspapers and literary journals. She has participated in European poetry festivals. Her first poetry collection titled Η μοναξιά της καμπύλης [The loneliness of the curve] (Κέδρος, 2015) was shortlisted for the Award for Newcomer Poet of the Hellenic Authors’ Society (Yannis Varveris Award), as well as for the State Award for Newcomer Author. Puente, her second poetry collection, is published by Polis (2020).

Maria Archimandriti spoke to Reading Greece* about her latest poetry collection Puente, which “constitutes, above all, an attempt to depict, in a poetic way, our journey toward the other human being”, commenting that “the primary bridge that is poetically depicted in the book refers to the transcendence of self as a prerequisite for the meeting with the Other”. She explained that “initiation to Puente’s world presupposes a kind of familiarity through which an internal submersion is made possible”, and concluded that “the poems of the book reflect the experiences of modern individuals and bring to the fore the various different aspects of reality”.

Your last poetry collection Puente was recently published by Polis. Tell us a few things about the book.

Puente is my second poetry collection following The loneliness of the curve. It was written within a period of more or less four years. Puente constitutes, above all, an attempt on my part to depict, in a poetic way, our journey towards the Other, the other human being, a meeting which presupposes a reconsideration of existing ways of co-existence and thus the development of new modes of thought and behavior.

In Spanish, puente means bridge. Which are the various connotations that this ‘bridge’ acquires in the book? What role does your poetic language play in this respect?

The book is titled Puente for two primary reasons. The former has to do with its theme, that is the need of modern individuals to build bridges with their respective ghosts. This need leads to a transcendence of the self, through a journey of internal quest during which memories are brought to the surface, desires and narrations from the unconscious are unearthed, while their mortal nature and deficiencies are put into question. The primary bridge that is poetically depicted in the book refers to the transcendence of self as a prerequisite for the meeting with the Other.

The latter has to do with morphology: the poems of the collections are stones supporting the pillars, the book’s distinct units, which, through four prose-like poems, connect with each other in order to form the bridge’s arc. The book has been written by having the form of a bridge.

The notion of time seems to be a recurrent point of reference in your poetry. How is this time defined in your writings?

I reckon that, at this point, we should distinguish between the linear time of our daily routine and the extended time of our spiritual life. The latter is much closer to the notion of time in my poetry. Non-linear, irregular and unruly, the poem’s time aspires to comment on the immobile time of immortality. Within this framework, my aspiration was to free the poem of time, so that resting out of time, the poem’s meaning is received in its integrity by the reader.

In her review of the book, Barbara Roussou uses a cinematic terminology in order to pinpoint a visual illustration of the poems. How would you comment on the intricate relation of image-reality-language?

It was a conscious decision on my part to lay emphasis on images as the main poetic means of the book, given that my aim was to build a world for the reader. Initiation to Puente’s world presupposes a kind of familiarity through which an internal submersion is made possible. I wanted to provide the reader with familiar stimuli, images that would awaken his/her memory. My intention was for my poetry to appeal to the reader’s own experiences. At least that was my intention.

In your own words, “the poems of the collection refer to modern reality and its relation to both its virtual and metaphysical dimension”. How does poetry converse with the world it inhabits? Could poetry be used to imagine what could be radically different realities?

There is the quantum nature of poetry, to which poetic time, which is by definition timeless, plays a pivotal part. Poetry, in its timelessness, constitutes the dreamy illustration of the real and contains our infinite reflections. The readings of our own self within the poetic space are definitely finite.

The poems of the book reflect the experiences of modern individuals and bring to the fore the various different aspects of reality. The harsh reality, the virtual reality, the promising, metaphysical reality, all comprise a world of the continuous re-definition of the self.

“At the end of every bridge, there awaits our redemptive self, and thus a new perception of the world”. Tell us more.

If I had to further explain these words, I would say that every attempt to transcend our self and to appease our memory, every effort that brings us closer to forgiveness, rewards us with a new prospect of our self, and of the world that surrounds us.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE