Barbara Roussou is a Faculty Member of the Department of Theory and History of Art at the Athens School of Fine Arts. She holds a PhD in Modern Greek Language and Literature (University of Athens) and a PhD in Theory and History of Art (ASFA). Her research interests focus on the interrelation of gender-literature/art, women’s discourse and image, the Greek literary field of the 19th century and modern Greek poetry (with emphasis on the period 1990-2020). She writes poetry reviews on print and online literary magazines. She has participated in international conferences and collective works. She wrote the postface and edited the work Ποιήματα τραγικά [Tragic Poems] by Antonousa Kambouraki (Stigmos, 2021). Ηer latest book Η περιπέτεια του ελεύθερου στίχου στην Ελλάδα. Από τις απαρχές έως το 1940 [The adventure of free verse in Greece. From the start to 1940] is underway.

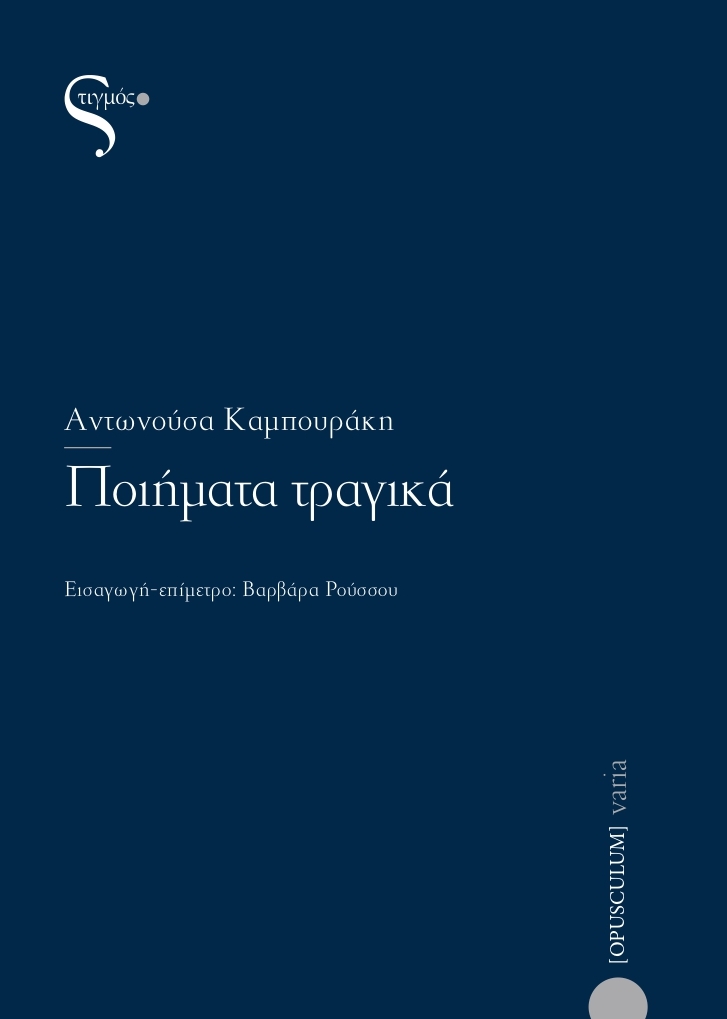

Aντωνούσα Καμπουράκη -Ποιήματα τραγικά [Antonousa Kambouraki -Tragic Poems] (Stigmos, 2021), with your introduction, constitutes the first complete female Greek poetic work published. Tell us a few things about the book, its content and its writer.

Tragic Poems by Antonousa Kambouraki is a work of major importance vis-à-vis a complete mapping of modern Greek literature of the 19th century. It is a single poetic composition of 2800 verses which, in addition to being the first work by a female Greek poet to be published under her full name, is also the first, and closest to the respective events, testimony of the Revolution of 1821 in Crete, fueled by the rich Cretan oral tradition, including experiences of the poet herself from the Revolution and testimonies from activists. The poem was published in 1840 in Syros, where Antonousa Kambouraki from Chania, as she proudly signs, took refuge after the failure of the Revolution in Crete. She was a woman of great courage and daring, about whom little is known. She was born in Chania between 1780-85 and died in Athens in 1875. She had lost her husband in the battles in Crete, while her son and her second husband also died. She left from Syros and lived for years in Messolonghi, while she probably stayed in Nafphio and finally in Athens where she died. She wrote other works as well – three plays of minor literary value and a poetic composition about the events of the movement against king Othon, a work equal to Tragic Poems – all on the Greek Revolution, especially in Crete.

Since the late 80s gender has been considered a tool that can make sense of how we perceive historical knowledge while in the past it had no place in stories of war, diplomacy, economics. The study of such historical cases as well as literary examples proves the permeability οf the boundaries between the public and the private, as well as women’s exit strategies. How have gender studies changed the way we perceive and study History?

Indeed, gender and its interdependence with nation, class and other identity constituents has changed the way we perceive the recording of history and at the same time the history of literature. The importance female experience has acquired, of course within a broader context of a change in the way we perceive History in general (e.g. history from below, microhistory, history of emotions etc) has opened new fields of study. The feminist perspective on history was linked with major issues and promoted their study, such as education, family, aspects of social life (e.g. charity). New elements are thus added to the whole range of historical research, that allow us to expand our understanding of what history is; to perceive history in its entirety and not as a compilation of war, diplomatic and economic events and the result of the actions of just a few people, always men. That’s what is important: the fact that women emerge as historical figures while they were previously absent and invisible to the historical science. To return to the history of literature, on the occasion of the 200 years since the Greek Revolution of 1821, there came to light the contribution of women to the revolutionary struggles, e.g. on the issue of philhellenism. We studied again, apart from Kambouraki, the impact of the Revolution on women’s literature, which offered a new perspective on the way literature perceived the Revolution.

In recent years there has been a great deal of international research interest in the presence of women in literature from antiquity to the 19th century. This is how masterpieces have come to light, which for centuries remained in the dark or were valued in a wrong, stereotypical way. Do you consider that such revisions and innovative theories could contribute to the renewal and enrichment of the literary canon?

My answer would be yes if I thought that we should talk about a canon and even treat it as sacred, or that we should accept multiple canons, e.g. a women’s literature canon. The literary canon is a changing institution and literature is influenced by institutions; in fact, it itself comprises elements of an institution. At the same time, however, we must admit that there is a general acceptance of the presence of an ‘official’, usually national canon, or of a number of canons. And so, let us ask ourselves whether the return to the forefront of important female works easily and unquestionably allows their inclusion in the ‘official’ canon given that it was far too late that the female literary creation was reviewed on equal terms with the male one, while there prevailed the transfer of naturalized qualities to the female subject, such as sensitivity and tenderness. Μuch more so if women’s works are not recognized as masterpieces. After all, gender still creates an ambivalence towards women’s works and their study, and I reckon that prejudices about the gender of the creator have far from disappeared. However, the emergence of women’s works, even if not masterpieces, leads to a revision in the field of literature by adding new elements to the huge puzzle, triggering new perceptions about our understanding of literature, as well as history.

Similar attempts have also been made in Greece. Let’s consider for instance Ανιχνεύονταςτην «αόρατη» γραφή -γυναίκες και γραφή στα χρόνια του ελληνικού διαφωτισμού-ρομαντισμού [Recording the ‘invisible’ writing – women and writing during the Greek Enlightenment -Romanticism] by Sophia Denisi, which brings to light women’s writing activity of the 18th and 19th century. As you also have a deep knowledge in the field, which do you consider to be the main characteristics of Greek female writers of the period, both in terms of form, language and content? How did they converse with the respective European literary trends?

Sophia Denisis’ book constitutes a strong point of reference, the result of many years of research. Indeed, it brings to light the entirety of women’s literary production until about 1880, in every field: translations, poetry, prose, theater in parallel with references to articles. Thus, for me it is the basis of my work and much more given that Sophia Denisi paved the way for me to study the 19th century, to be exact the female 19th century. My own cycle is an integral part of Denisis’ work in that I delve into Greek female poetry from 1840 (Kambouraki) onwards since my research moves from 1880 to around 1910. Withinthisframework, Ihadthechancetosystematically study the various means of female poetic works.

The somewhat eccentric Athenian romanticism, what we know as the first Athenian school, initially dominated the creation of women. Later on, female poets followed the respective movements and trends in Greek literature and trends in Greek literature in general, while regarding language, they turned to the demotic. Women’s literary production was no different from men’s in form or theme. However, homeland as a topic was not as common as it was for men because high ideals were considered a matter of male and therefore robust poetry.The extent to which women came into contact with European literature depended on their education: a better knowledge of European trends began in the early 20th century and was linked to the gradual acquisition of women’s freedom: in education, in studies, in socializing with their peer men, traveling abroad, etc.

Ιn a recent essay for the University of Michigan on “revolt”, Vagia Kalfa commented that in the Greek history of literature, the notion of the political is male dominated, although alleged as universal, a case in point being the literary generation of the 1930s and the first post-war generation. Is there a place for women or LGBTQ people in the Greek literature of the 21st century?

I believe that the young and good poet Vagia Kalfa certainly has a point, especially with regard to the past. Today, the quantitative data show an increase in the number of female poets from 2000 onwards, which further sharply increases from 2010 onwards (almost reaching the number of male poets); at the same time, a respective quality evaluation highlights a great number of quite and very notable female poets. In many cases, gender becomes a key issue in their work as a primary socio-political element. Thus, female poets develop a special dynamic on the basis of gender and gender discourse that becomes accusatory, often intense or experiential, which in no way can be ignored in the field of contemporary literature.

A much smaller number openly promotes its inclusion in the LGBTQI community or identifies itself as queer, that is beyond the dual dipole, where queer is closely interrelated with other elements, e.g. political/class. Non-binary individuals articulate a discourse, which is gradually gaining power, is different, experiential, performative, subversive and insurgent. In this respect, we are at a turning point, especially in poetic speech.

Could a multi-faceted socio-economic phenomenon, such as the crisis or the pandemic, trigger a new poetic ‘cosmogony’, which could possibly lead to a new poetic ‘generation’? Ifso, based upon which poetic and aesthetic criteria?

Your question raises a major issue and opens a whole new discussion. I wouldn’t say that the word cosmogony corresponds to what is currently happening in the poetic landscape; yet, there are certainly not just some differences compared to the past but also some breakthroughs in certain fields, e.g. in the diversity of form and its relation to other arts. Τhus, almost automatically the conditions and the respective poetic reaction give shape to various groups of young male and female poets that constitute what we call a ‘generation’, which doesn’t necessarily mean a common course or collectivities etc, but age groupings which almost naturally have common features, as well as divergences. This poetry is more than diverse, while it draws from numerous sources, from literature to scientific and philosophical discourse; it is placed next to them, as closely related and not significantly divergent. The notions of lyricism, crypticity and especially the social role of poetry are approached anew by the poets.

I would say that the younger generation is revisionary vis-à-vis the poetic and generally the historical past, strongly critical of the present, redefining its principles regarding the poetic language, the poetic purpose and the perception of poetry as the most noble of arts. At the same time, there is a plethora of poetic trends and perceptions which usually yield high quality works. Thus, I implied above a series of criteria on the basis of which we can evaluate contemporary Greek poetry. Certainly, a lot has been written about this ‘generation’ of younger poets and I intend to systematize these assessments in such a way as to map poetry from 2000 to 2022 so that the criteria for its evaluation are collected and categorized.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE