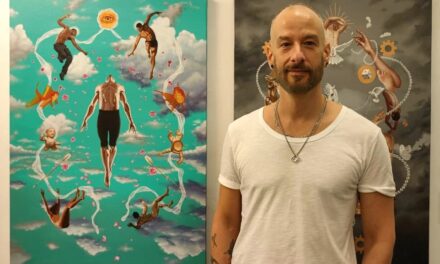

Panos Profitis is a compelling voice in contemporary art, recognized for his innovative sculptural installations that combine industrial materials with deep conceptual ideas. Drawing inspiration from classical sculpture, while utilizing industrial materials such as aluminum, iron, epoxy, plaster and concrete, he explores themes of movement, ritual and the human condition.

He blends smooth metallic surfaces with biomorphic and mechanical forms, creating immersive environments that combine performance, installation and sculpture. Drawing from ancient mythology and literary sources, such as Dante, he creates a hybrid and distinctly postmodern language, treating the body as both symbol and myth.

His current exhibition, La Bocca La Grotta (The Mouth The Cave), presented at the MOMus–Alex Mylona Museum, explores the tension between archetypal dualities: darkness and light, upper and lower world, comedy and tragedy, life and death, the earthly and the metaphysical.

Panos Profitis is the winner of the Art Athina Young Artist Award 2024. He holds an MA in Visual Arts (2016) from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, specializing in site-specific and installation art and a BA from the Athens School of Fine Arts (2013). He also holds a degree in Graphic Design from Akto Art & Design College (2008).

His work has been exhibited in Greece and abroad. He has received numerous awards and fellowships: the NEON Organization scholarship for his MA studies (2015–2016); the Hugo Roelandt Prize for his master’s thesis (Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp, Hugo Roelandt Estate & Objectif Antwerp, 2016); the SNF Artist Fellowship from the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (2018).

Panos Profitis spoke to Greek News Agenda* about his paradoxical practice, his references and shares his views about the arts in Greece.

What inspires you to start a project and how does the process evolve?

I wouldn’t say I have a single source of inspiration; I draw from many things, often contradictory; everyday life, even simple human gestures, may spark an idea. Such moments have been the inspiration for my performances; people cracking sunflower seeds on a street corner or two elderly women descending a marble stairs after Sunday service.

Albeit an atheist, religious art and Byzantine iconography also inspire me. The way figures are represented and form part of the architectural space, which becomes the stage for ritual with roots in ancient drama, has always fascinated me.

I find peace in entering empty churches in the city center, especially on hot summer days, when they hold an otherworldly coolness. One can sense that religion in this form is fading, giving way to the cult of production and consumption. Our phones and tablets are the new shrines, the new tableaux vivants.

Monumental art also concerns me because of its political dimension. We are living through an era where symbols and figures are being removed from public space, yet the system that elevated them remains intact. At the same time, contemporary politics has allowed for a kind of image-worship—again, without confronting the structures that sustain it. I also enjoy finding inspiration in cinema, theater, travel and reading.

Once I gather the material I need, the creative process unfolds alongside my research; exploring, reading, collecting visual material and experimenting. I frequently stumble upon fascinating visual references in old encyclopedias or museum catalogues. I experiment, I often fail.

The process is much like cooking: you get your hands dirty, mix ingredients…In my case, chaos reigns; materials, sketches, and tools are scattered everywhere. Once the work is completed and order is restored, I prepare for the next project. And all this while listening to music.

Art sometimes conceals, sometimes reveals. How open to interpretation do you consider your work to be? How easily do you think the public can relate to it?

I absolutely agree with this statement. I strongly believe in the enigmatic nature of art. Works of art may describe something, but at the same time, they conceal it; just like music. I consider my work to be open to interpretation. I do not want to strictly limit it rationally, focusing on a rigid scientific approach or a heavy conceptual framework. Of course, there is always an axis that runs through my practice and I believe that, to a certain extent, there is a core from which I draw my themes.

Beyond my intentions, I am concerned with my work evolving through the eyes and thoughts of the audience. I am interested in hearing views I did not even have in mind. This way, a very fruitful dialogue develops regarding an artwork that is exhibited in the public sphere.

I don’t know exactly how easily the audience can relate to my work; it depends on many factors, it’s a two-way relationship: It has to do with how familiar the audience is with contemporary art or how much time they are willing to invest in interpreting the work of art. Sometimes barriers and prejudices may arise—questions like “Is this really art? What is he trying to say?”. These reactions are sometimes justified, other times are frivolous and superficial.

At the same time, it also has to do with the artist’s desire to use auxiliary tools to create a channel of communication with the audience. These tools can be a text, the title of the work, the dialogue and conversation surrounding the work, a critical analysis, or even personal interviews with the creator about their work.

I believe that when the public regularly attends exhibitions, it will gradually develop mechanisms that will facilitate understanding of the work. However, the issue of communication does not only concern the public and the creator; it presupposes a state that has cultivated an art-focused educational system. What we see, however, is that the arts have been largely excluded from public education, thereby depriving the visual arts of their important contribution to the formation of the individual from an early age.

Are there recurring elements and symbols in your work?

Yes, I would say that there are elements and symbols that recur in my work. I have an almost obsessive relationship with the mask. In my work, the mask is a tool for projecting political, anthropological and philosophical issues. It’s an object that appears in almost all cultures. In our culture there is a deep connection that has been established since ancient drama and rituals.

In Aristophanes, for example, the πρόσωπον (face/mask) is the most exposed part of the body—subject to absurd and comic misfortunes. The face thus carries a timeless symbolism in art—whether as portrait, bust or mask—and in everyday life.

When inverted, these sculpted heads reveal emptiness, exposing their theatrical, false nature. An exhibition space filled with such masks resembles an abandoned stage.

What are the issues that concern you as an artist?

I cannot easily define the issues that concern me. The reason is that most of these works take on a life of their own. They abandon me, they become autonomous like the characters in a play.

Beyond symbolism, my intention is to highlight that our society, including the cultural industry, wears masks. Our era is covered by a veil of hypocrisy, and this veil also covers political and cultural institutions. In most cases, institutions become “mimes” rather than voices, and this has spread to every aspect of everyday life, making us part of this great human comedy.

What criteria must be met for you to feel satisfied with your work?

Personally, I feel fulfilled when I enjoy the creative process, which is very similar to the feeling of playing and experimenting. That is, when the body and mind function in a state of excitement and optimism about what may arise in terms of projects or situations. It is important that things function effortlessly and evolve organically, unaffected by external interventions and pressures.

Another important factor is that this process is framed by a healthy professional environment where the creator is rewarded for their work and for the hours they have devoted to producing the work. When these conditions are met, I believe that any artist can feel a sense of satisfaction.

How do you view the artistic landscape in Greece?

I want to be optimistic about the future. Certainly, after the Documenta period, there was a blossoming of the artistic scene in Athens in particular; new spaces opened, foundations invested more in art and public programs and artists came from abroad and joined the local art scene, positively influencing the arts in Greece.

On the other hand, this entire situation was later sustained mainly through the personal efforts of cultural workers, with very little support from any serious state initiative aimed at genuinely supporting the majority of creators. To be honest, this field has never been easy, and those working in it are well aware of the challenges and difficulties. The art field is often inaccessible to many talented people who are excluded for social or economic reasons. We all need to push for a more democratic environment that will encourage new creators to continue their path in this sector.

For this reason, institutions play a crucial role—but they too need to be properly funded to develop their programs without such enormous difficulties. For example, in the Netherlands, the Mondriaan Fonds program supports everyone from creators to galleries, foundations and independent spaces, offering significant professional and artistic opportunities by funding galleries to participate in art fairs, which is usually very costly.

Here, the challenges are much greater; even such spaces lack proper financial support to promote artistic production. Especially for a peripheral country like Greece, such programs should be developed so that institutions (private or public) can also have the freedom to take similar risks, and so on.

Of course, it is very encouraging that certain museums are taking the initiative. The EMST (National Museum of Contemporary Art) has managed to open its doors, reaching a broader audience, while maintaining an international outlook by inviting artists and curators from abroad. In this respect, we see a successful dialogue on all levels, creating a communication channel between the local and international art scene.

Grants or awards, such as the one established by Art Athina, should be promoted so that similar initiatives multiply and promote new creators, who in turn will share their work with the public.

Personally, I believe there is an excellent level of Greek artists who contribute to the development of this country’s cultural industry, producing quality work with a contemporary approach. In my opinion, what we need is a consistent strategy aiming at their professional and financial support.

*Interview by Dora Trogadi

Artworks Courtesy of Panos Profitis, The Breeder Gallery

Intro photo ©Myrto Papadopoulos