Konstantina Korryvanti (Athens, 1989) has studied Political Science, History and International Relations. She has recently moved to the United Kingdom, where she works at the University of Essex. Mythogony (Mandragoras, 2015) is her first poetry collection.

Konstantina Korryvanti spoke to Reading Greece* about Mythogony, “a poetry collection inspired by female figures of Greek mythology”, that “touches upon the everlasting battle between male and female by re-introducing the divine status of women”. She comments that “poetry is a discursive form which allows for an imaginative exploration of the enduring visionary narratives of myths”, and adds that Mythogony is “a poetic project of self-awareness and self-reflection, with a strong focus on gender, social roles and norms”.

Asked about the prospects of Greek literature abroad, she note that “Greek poetry and particularly Homer have a continued impact on Anglophone literature”, which should serve as a model for further exchange, and concludes that “Greek poetry has become relevant again and it would be a pity not to take advantage of the momentum”.

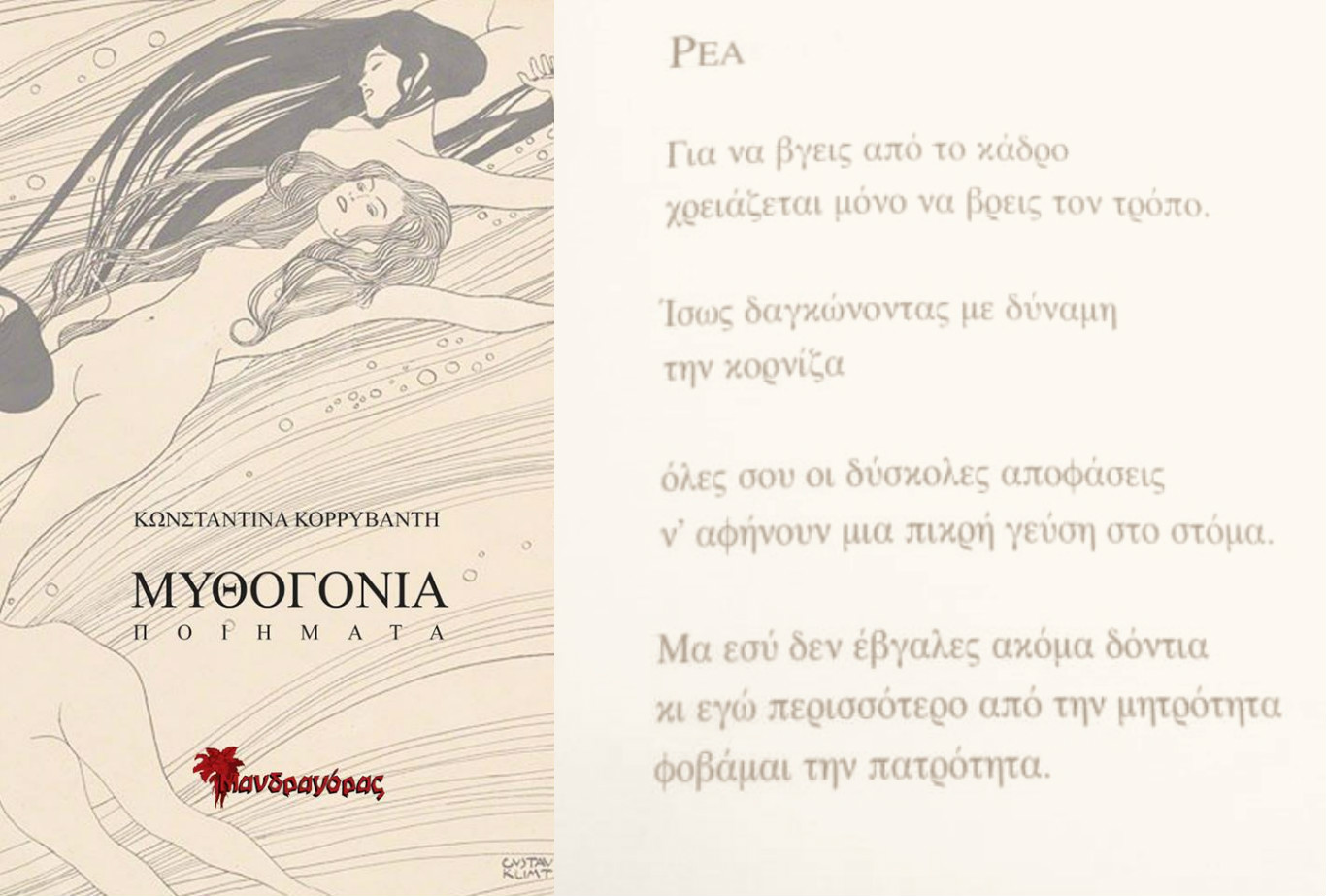

Your first poetry collection Μythogony received both the Maria Polydouri Poetry Award 2016 and the G. Athanas Award of the Academy of Athens the same year. Tell us a few things about the book.

Mythogony (Mandragoras, 2015) is a poetry collection inspired by female figures of Greek mythology. I was attracted to myths from an early age and I have to admit that Greek mythology excited my imagination to such an extent that it was almost impossible not to write this book. Mythogony touches upon the everlasting battle between male and female by re-introducing the divine status of women.

How important are such awards for a newcomer in poetry?

Receiving an award is always a welcome gesture that not only motivates the recipient to do more, but also conveys to others that such efforts are indeed appreciated. Mythogony was also a runner up for the 2016 debut poet’s award in the literary prizes of the Reader’s Magazine (Anagnostis) and was shortlisted for the 2016 Yiannis Varveris award for the best first poetry collection presented by the Hellenic Writers’ Society. I could not be more thankful for the tremendous amount of encouragement to keep getting better. However, I do consider poetry to be a process, a lifelong project and I know pretty well that at the end of the day, awards are just a pat on the back to carry on and work harder.

Ancient Greek mythology has always been a source of inspiration for writers. How are myths and archetypal symbols used in your writing?

Poetry is a discursive form which allows for an imaginative exploration of the enduring visionary narratives of myths. It is through their archetypal images and drama that we can address eternally important issues such as order, freedom, balance, love and death. As Roland Barthes nicely put it ‘myth is a type of speech chosen by history’. To build upon this thought, I have come to realise how easily myths go way beyond the public domain and concern us deeply on a more intimate level.

Classical mythologies had and will always have a place in poetry. There is a long list of poets who drew not only on ancient myths but also on the work of previous writers influenced by mythology. A striking example is that of Ted Hughes, who was greatly inspired by writers such as Robert Graves and W. B. Yeats. Mythological figures are also recurrent references in Margaret Atwood’s writings and have frequently appeared in Carol Ann Duffy’s poetry in a revisited way. This revisionary quality interests me the most. Retelling a story has a constructive power much needed and often hard won, especially for women struggling to challenge and transgress the patriarchal discourse.

Just to elaborate on this point, Adrienne Rich, acclaimed poet, essayist and one of America’s most esteemed intellectuals once said that ‘revision – the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entering an old text from a new critical direction- is for women more than a chapter in cultural history; it is an act of survival’. As I see it, and apologies for the terrible cliché, the only way to survive is to know yourself. Mythogony is, therefore, a poetic project of self-awareness and self-reflection, with a strong focus on gender, social roles and norms.

What about your use of female mythological figures only (with the exception of Triton)? How is woman, in all her roles and representations, imprinted in your poetry?

The 23 female mythological figures of the book serve as devices exploring further the female identity. Western mythology introduced women either as angels or devils. The contrast of Euripides’s Alcestis, who sacrificed her life to save her husband and Medea who murdered her children to get revenge for her husband’s betrayal is a perfect example of this. My Mythogony, however, stands in the middle and sets the woman at the centre of the universe where genesis begins. It was only just before submitting the final manuscript of Mythogony that I realized what my book was about.

Mythogony is mostly a poetry collection dedicated to the mother-daughter relationship. This is the core and the primary link between women and I could not have chosen a different starting point. In fact, the book opens with a quote by the American poet Sylvia Plath. Plath in a letter to her mother wrote: ‘I would like to call myself the girl who wanted to be God’.

What I mean to say is that even though, at first, mythology might seem an inhospitable terrain for women, if the reader overcomes the recurring theme of conquering gods and heroes, some rare qualities attributed to women can be witnessed. In Mythogony, even the less trained poetry reader can identify the woman as mother daughter, mistress and wife. Interestingly enough, my favourite role is that of the deserted or the loner – if you prefer – as it is a much broader category open to different interpretations.

The last two poems, however, are not female portraits. The 24th poem is about Anafi, a small Greek island in the Cyclades where the Argonauts found shelter during a storm. Anafi imprints and extends, therefore, the qualities of the Sea, yet another metaphor for woman. That is why Triton, a fish-tailed merman and demigod of the Sea made a fine conclusion. It appears that Triton as a young man said to be a messenger is the only one who can calm the waters.

It has been argued that the new generation of Greek poets is multicultural, multiethnic and multigenerational. What is it that makes a national literature appealing to a foreign audience? And, in turn, to what extent do Greek writers incorporate foreign influences in their work?

Emerging Greek poets have shown raw talent and great potential. The vast majority of them are well educated, hardworking individuals from all walks of life, with a strong commitment to poetry. Their work is independent from tradition but at the same time not altogether detached from it.

We have been fortunate enough to inherita highly influentialliterary legacy, so building upon it is an arduous and exhaustive task. Greek literature may have its own allure but when it comes to poetry you need to approach one reader at a time. While I believe word of mouth normally helps and should suffice in the domestic book industry, raising awareness on Greek modern poetry is key, if we are aiming at a foreign audience as well.

To put it in the right context, Greece has recently fallen under the spotlight due to the economic crisis and many young Greek poets were featured in relevant anthologies published abroad. Prior to those anthologies, the only Modern Greek poetry that you could find in mainstream bookstores in London was the unparalleled poetic corpus of C.P. Cavafy, an extended bibliography on Seferis and in some cases poems of Ritsos.

Launching abroad anthologies of contemporary Greek poetry was, therefore, a great kick start. Greek poetry has become relevant again and it would be a pity not to take advantage of the momentum. If there is a just right moment for everything, I think that is high time for public sector and private initiatives to join forces. A promotion campaign should be the next step.

From my experience abroad, I can assure you that ancient Greek poetry and particularly Homer have a continued impact on Anglophone literature. Derek Walcott, Seamus Heaney, Michael Longley, Anne Carson, Louis Glück and Alice Oswald, just to name a few poets, have returned to the old texts several times; still paying homage to ancient Greek models and themes. Why not pursue further exchange?

In looking for foreign influences in our writings, I am pretty convinced that modern British and contemporary American poetry are the dominant paradigms. This is no surprise, given that English is the most accessible language to us and a considerable number of young Greek poets have studied in the U.K. Needless to say how significant has been the contribution of Greek literary magazines, such as Poiitiki,Mandragoras and more recently Farmako and Thraca to this exchange.

To speak for myself, my growing appetite for foreign poetry led me to somehow match the Greek poets I have cherished the most with British, Irish, Americans, French and Italians. This way I have teamed up C. P. Cavafy with W.H. Auden, Andreas Empeirikos with Ted Hughes, Matsi Chatzilazarou with Joyce Mansour, Louis Glück and Jane Hirshfield with Jenny Mastoraki and Maria Laina, Alda Merini with Katerina Angelaki-Rooke.

“I saw my personal fears reflected in those of hundreds of young people who have put their hopes in the heavy industry that is higher education”. How does Brexit influence the academic and cultural mapping of England? What are the prospects ahead?

The U.K’s withdrawal from the EU has started and no one knows what future holds. If there is one thing that keeps my hopes high that’s the inclusivity and the internationalism of the UK Universities. I joined the University of Essex in early 2016 and since then I have been co-ordinating the Doctoral Programme of the Law School. As we like to say here at Essex, we are proud to have the world in one place. So, we shall keep it this way.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

*INTRO IMAGE: Kristina Bratuska

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE