Art critic Fotini Moustakli, in an article to Greek News Agenda is examining the contribution of Greek and foreign painters in influencing people worldwide to support the Greek cause in the 1821 Greek War of Independence. Fotini Moustakli has a Bachelor’s Degree in Art History and Archaeology with a minor in European Middle Ages from Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB) and holds a Master’s Degree on Visual Culture from Lund University, Sweden, focusing on integrating virtual technologies (VR, among others) in museums.

Introduction

The 19th Century went down in history as a period marked by turmoil, revolution, independence and the creation of nation states across the Western world. Also known as the Age of Revolution, Europe witnessed a series of uprisings following Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, including the Spanish, Portuguese and Greek Revolutions among others.

The Age of Revolution more particularly coincided with the rise of romanticism – a cultural movement where art was exalted in naturalism, embraced emotion and the fruits of personal freedom. Artists like Delacroix and Caspar David Friedrich turned to their imagination for inspiration, going against their predecessors in the Enlightenment movement.

Romanticism in the arts translated into the political revolution against the ‘old order’. Art mimics life in the dichotomy between the two ages from 17th to 19th century, with Classic and Romantic art movements paving the way for the political era of revolutions: the age of stability against the age of revolutions, traditionalism against progressivism, imitations of life against creations of new worlds through artistic imagination exploring the unknown.

The spirit of Revolution and desire for freedom was not limited to the Greeks, as many Europeans strongly identified with the Greek struggle against the Ottomans. There are several -political, historical and cultural- reasons for this connection. One reason was the undeniable impact of Ancient Greek civilization, serving as the political and cultural foundations of what has eventually became Europe. With Ancient Greek civilization at its epicenter, some European powers saw their cultural and philosophical origins embedded in this culture. Indeed, Ancient Greece held a unique place in the Western European imagination also in art.

The contribution of foreign painters creating an awareness of Modern Greeks as a free people and a symbol of revolution representing Europe took form. As such, philhellenic sympathy was carried by the press and the arts, theater, literature, poetry. The transnational nature of this general European emotion motivated intellectuals to support,finance and even travel to Greece to assist in the Greek struggle, as they felt a deep connection and sympathy for the plight of the Greeks under Ottoman rule.

Against this background, I will examine two paintings, The Army Camp of General Karaiskakis (1855) from Greek painter Theodore P. Vryzakis and the Ruins of Missolonghi (1826) from French painter Eugène Delacroix, as striking representations of the visual history of the Greek Revolution.

- A Greek representation

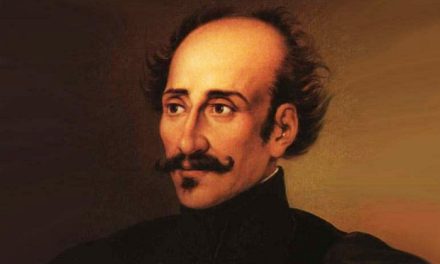

Theodoros P. Vryzakis is considered to be the first painter of post-Ottoman Greece and the founder of the Munich School. Vryzakis’s father was executed by the Ottomans early on the War of Independence, moved to Munich in 1832 where he attended a school for orphans of the Greek revolution. He subsequently studied fine art in Athens, and returned to Munich in 1844 to study at the Academy of Fine Arts. There, he developed his artistic talent and interest, drawing his inspiration mainly from the 1821 War of Independence.

He exhibited the oil painting ‘The Exodus from Missolonghi’ at the Paris Exhibition in 1855. He made at least two other copies of the painting, two of which were destroyed in the 1929 Missolonghi fire. The third can be viewed today at the National Gallery in Athens. Vryzakis is considered to be one of the foremost Greek romantic painters of the 19th century. His oil paintings are characterized by a nostalgic style and atmospheric colors.

The Army Camp of General Karaiskakis 1855 depicts the gathering of the Greek army in Phaliron, just south of Athens, preparing to capture the besieged Acropolis in 1827.

The Army Camp of General Karaiskakis 1855, oil on canvas, 145 x 178 cm

In the foreground, Greeks and philhellenes are assembled, wearing the Greek national costume and the blue European uniform respectively. In the center, the most radiant figure of the painting, a man wearing a bright national uniform (foustanella) is leaning on an ancient ruin. With his left hand he is pointing toward the East. The allusion to Ancient Greece comes in direct contrast with the Christian Orthodox priest front-right, who is blessing the fighters.

The diagonal axis of the painting guides the eye of the beholder where the leaders of the army clearly intend to go: the Acropolis Hill. As such, the Acropolis is placed in the background of the painting, visible along with other landmarks, such as Ymittos Mountain and Lycabettus Hill.

It is interesting to note that on the left, the man in the blue Bavarian costume is the German captain Karl Krazeisen. He came to Greece in 1826 and fought for the Greeks for about a year. He fought during the reconquest of Acropolis and played a major role in the depiction of Greek fighters and generals of the 1821 revolution. The images in his lithographies were virtually identical to the people he immortalized. Thus, he gave other artists an exceptionally vivid idea of what the Greek heroes of the Revolution looked like.

By giving Krazeisen a forefront position in his painting, Vryzakis can be said to be showing gratitude to the Krazeisen’s contribution to the Greek struggle. He becomes the allegory of all European fighters that fought along Greeks for Greece’s independence.

Thanks to Krazeisen’s lithographies, Vryzakis could faithfully reproduce all of the key Greek fighters, placing them on the hill near the Greek flag. One can see many familiar figures of the War of Independence: Karaiskakis, Makrygiannis, Tzavelas, Notaras, a Scotsman named Gordon, an Englishman called Hastings and Karl von Heideck looking towards the Acropolis through a telescope.

The colors are gold, red and brown, characteristic of Vryzakis’ work. The anticipation of the subject of the painting –the siege of Acropolis– is building up the suspense but it is gently contained by the warm color intervals.

- Foreign representation

In the first half of the 19th century, the Greek War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire inspired young artists in Paris. In the struggle of the Greek people, they saw their own ideals of freedom, linked to the ideas of the French Revolution. The Chios massacre (1822) becomes immortalized Eugène Delacroix’s painting Scène des massacres de Scio which was exhibited in the Salon in Paris in 1824, thus reaching audiences in the French capital. Delacroix sees an enthralling and modern subject in the Greek revolution, and even though the artist never travelled to Greece, the faraway land remained a distant imaginary fueled by his readings.

Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi, 1826, oil on canvas, 208 x 147 cm

In Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi 1826, we see the silhouette of a young woman in the foreground, standing in the ruins against a dark background. She is wearing a deeply indented white dress and a blue coat tightened at the waist by a yellow scarf; on her head, she wears a scarf with colorful patterns. The woman is pale, dressed in the Greek national costume and she is both kneeling (symbolizing defeat) and standing (symbolizing victory). Her eyes are wet with tears and she reaches out in an imploring gesture.

In the background, on the right, we can see a man with dark skin dressed in an oriental suit with red puffy harem pants and a black coat tightened at the waist by a wide draped belt with pistols. He is wearing a red turban and his face is turned sideways to the left, seemingly indifferent to the young woman while with a conquering gesture plants his dagger in Greek soil. The body of the young woman forms a pyramid which leaves from the lower left corner all the way to the upper right edge of the painting and is outlined by the line of clouds. The ruins at the bottom of the painting and the heap of stones in the foreground form other parallel diagonals. The dominant tones are cold, as evidenced by the young woman’s blue coat, the dark grey landscape and the overcast sky. However, they are given warmth by the blood dripping from the pants of the Turkish Janissary as well as the shoe of the young Greek woman and the lapel of the dead man’s sleeve.

The violent contrasts between the dark and the strongly lit parts, like the body of the young woman, are what make this painting fascinating.

Conclusion

While their commonalities are arguably more outstanding, paintings by Greek and foreign artists highlighted above differ in certain important characteristics. In particular, the difference in style and implied purpose need particular mention.

An archival realism is not uncommon in depictions by Greek painters. Given the detailed portrayals and accurate landscapes, their interpretations and depictions exert a sense that the artist knows the actual land and the people. This also extends to accurate depictions of foreigners in paintings, so much so that most of them are identifiable, historical personalities. This was perhaps in order to immortalize the times as they were, and to show gratitude to those foreigners who came to the aid of the Greek struggle against the Ottomans. In a way, these artworks commemorate victories, important events and figures. In other words, these paintings do not merely express nationalistic sentiments alone and invoke such reactions from the beholder, but they also create some form of documentation, a depiction of a moment in history that led Greece to its independence.

As for foreign artists like Delacroix, allegories overtake this local and possibly incidental tendency to record history in art. Most of his paintings about the Greek Revolution depict personifications of Greece, the Greeks, and their struggle – represented by a group of exhausted civilians, a mother killing her son in a desperate attempt to save him from an ominous future, or a woman in a traditional outfit rising from the ruins of the past. Anachronistic elements are liberally used and different epochs in Greek history are represented simultaneously in a single painting. The purpose seems to be to express a

distant yet strong sympathy with the plight of the Greek people, and the foreign perception is thus directed towards ideas, ideals and the imagination, instead of first-hand accounts and archival features. This philhellenic approach romanticized the Revolution more than the Greek approach, which instead sought to create historic monuments on canvas.

Read also: A Digital Research Platform for the Greek Revolution of 1821, Greek Independence Day: 25 March, 1821 | The Making of a Modern European State, Michalis Sotiropoulos on the History of Greek Liberalism in the 19th Century, Hellene, Romios, Greek: Collective Identifications and Identities