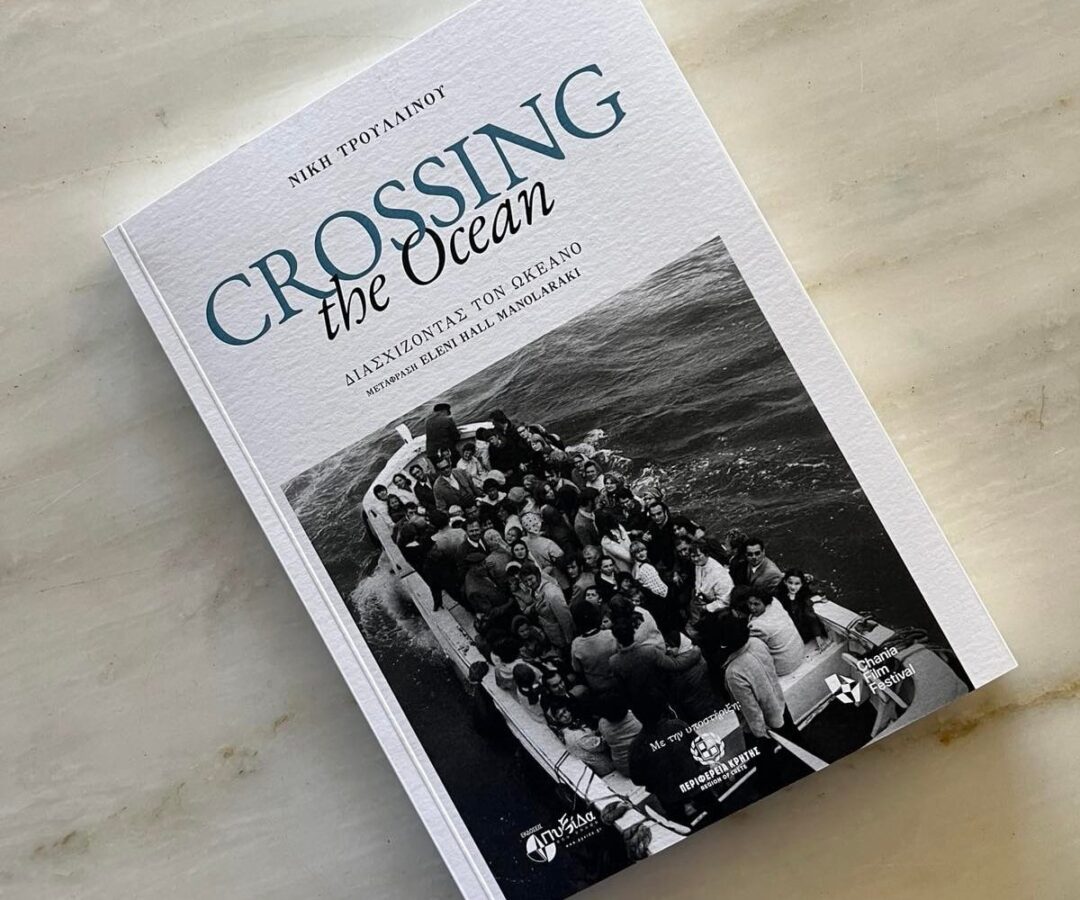

The bilingual edition Crossing the Ocean [Pyxida tis Polis Editions, 2025] by Niki Troullinou, published with the support of the Region of Crete and the Chania Film Festival and translated into English by Eleni Hall Manolaraki, comprises twelve short stories that follow the paths of Greek emigrants – ordinary heroes, much like ourselves – as they cross oceans in search of a better future. Their journeys are long and difficult, marked by loss, bitterness, hard work, nostalgia and loneliness. Yet, they are also filled with hopes, dreams, joys and discoveries.

Like descendants of Odysseus, these trailblazers wander the globe, forever caught between their love for their new homes and their deep ties to their birthplace. And the journey, ever unfolding, carries them forward, their hearts navigating the tides of longing and adventure. In its Regional Governor’s Greeting, Stavros Arnaoutakis notes that “Cretan men and women, like other Greeks, have roamed the roads and seas of the known world since the days of Odysseus. Beginning with the late 19th century, we collectively crossed the Atlantic and other oceans looking for work, sending much of what little we made back to our families”. Troullinou guides readers on a journey from Crete to the world and back to the island. Her stories “speak of tradition, progress, friendship, loss, courage, and love”. Above all, readers are invited to “walk the labyrinths of Memory, individual and collective”.

Reading Greece* spoke to Niki Troullinou about the book, discussing how the idea of a literary mapping of these migratory paths came up, the feelings emigrants had in their long and difficult journeys, and how they turned into dreams and hopes for a new world ahead.

The book follows the paths of Cretan emigrants as they crossed the ocean in search of a better future. How did they idea of a literary mapping of these paths come up?

This story goes back quite a while, to the pre-COVID days. With the musical ensemble Ode – Poros, we put together a performance that combined music and spoken word, tracing the history of Greek migration with a special focus on the Cretans who left their homeland behind. The idea was this: now that foreigners, migrants or refugees, are arriving at our own doorstep, and we so often fail to open the door, might it be time to look back? Who were we, once? How many hundreds of thousands left this land, not only long ago, but even recently? One Greece here, another abroad – an absolute, undeniable truth. Perhaps it’s time to remember. The performance turned out beautifully. It toured the whole island, with not a single empty seat. And soon after came the invitation to perform in America. We were overjoyed, passports in hand, and then, along came COVID. Perhaps, in some way, that dream remained unfulfilled. A quiet longing.

Around the same time, my dear friend Eleni Hall Manolaraki, an Associate Professor of Classics at the University of South Florida, a Greek-American immigrant and a naturalized American citizen, kept urging me: “Come on, let’s make a bilingual book”. I had only a small slice of American experience to draw from. I gathered material, texts from four of my previous books, along with diary entries from my stay on the West Coast years ago. But it quickly became clear: much more work was needed here. So, I set to work, and the journey that followed was a beautiful one. Writing while searching, searching within myself through the act of writing. The subject, of course, comes with its challenges: so much has already been written, already said – how do you escape the clichés? And then, unexpectedly, a few rare photographs would arrive, precious little winks from the past. Everything I wrote travelled by email to America, where Eleni translated it. Then it would come back, move forward again, shared with others who offered their insights, corrections, factual clarifications that needed to be made. We worked intensively for two years. But publishing the book proved difficult. The Region of Crete, that had also supported the concert, stepped in and offered a solution. A carefully crafted bilingual edition, printed on fine paper, in a limited number of copies. For now, it is not for sale. Instead, it has been passed from hand to hand among members of the diaspora returning to Crete for their summer gatherings. It brought joy — and we, in turn, hope that we’ll find a way to take it further. To carry it farther. Let’s just say a beginning has been made.

You lay special emphasis on depicting the feelings that these emigrants had in their long and difficult journeys. How did loss and nostalgia turn into dreams and hopes for a new world ahead?

I believe that, as a writer, I have a duty to cast light upon the emotional world of migrants – to delve into their inner landscapes, into what they carry in silence, just as much as into the harsh realities that drove them to leave. And, alas, they are still leaving; this time the younger generation, which was forced to depart due to the recent economic crisis. Things have changed so much. Once, it was our own who left, pushed away by poverty, deprivation, and joblessness. They abandoned a homeland – they hurt, but they still left. And now, suddenly, in the 21st century, it is our brightest minds who are leaving — with brilliant educations, with PhDs. And we watch them go, stunned, helpless, asking ourselves: “Where did we go wrong? What have we done?” This, I would say, is the heart of the short story Men Don’t Cry.

On the other hand, since I have always been deeply drawn to History, I felt compelled to write about the Jewish child who was adopted in America after the war, about the Greek pilot who flew in Korea, about the first-generation immigrant who returned home and built the finest hotel in the South. And, also, about the Vietnam veteran – a different kind of migrant – who finds his way to southern Crete and learns to cook Stuffed Vegetables, Tweaked. You see, once again, I’m writing short stories, everyday tales of ordinary people whose lives are shaped by the great sweep of History. I truly love this – wars, migrations, the shifting needs of each era, and the everyday people caught in their tide: How do they feel? What do they do? Where do they go? What do they hope for? Will they make it?

I really need this broader historical canvas in order to write – it’s a kind of adventure in itself: to read books, dig through old newspapers, study the material, learn the landscapes, even travel there, if possible. The places, geography itself, and, of course, the leap all of it gives into fiction. Because indeed, you stand on History and on real stories, but what you aim to write is Literature.

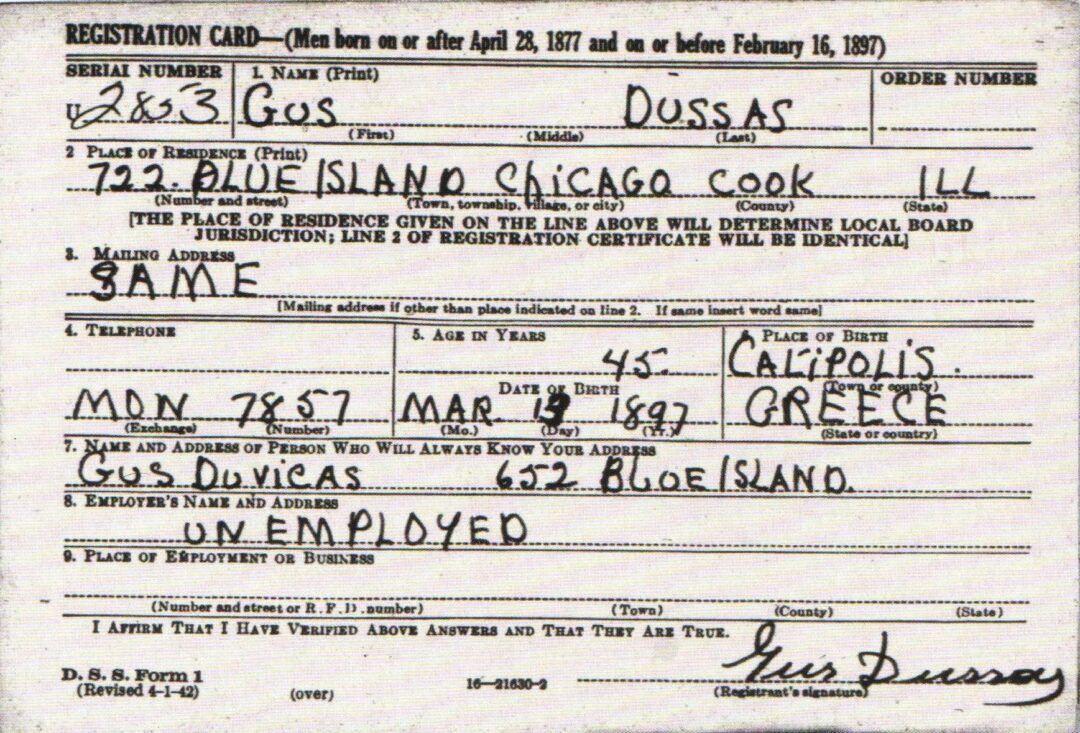

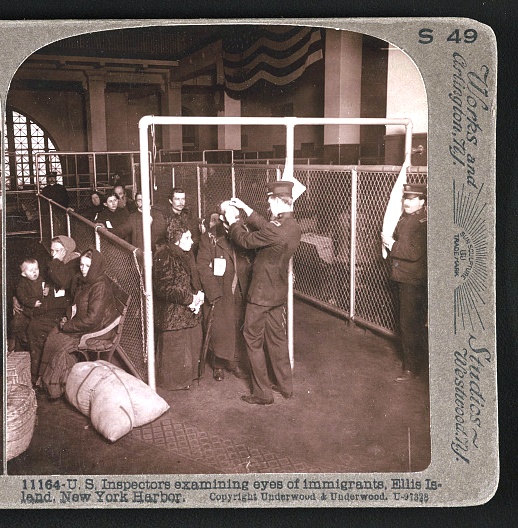

The book also contains important photographic material which constitutes an invaluable treasure safeguarding memories and recollections. Tell us a few things about these photos.

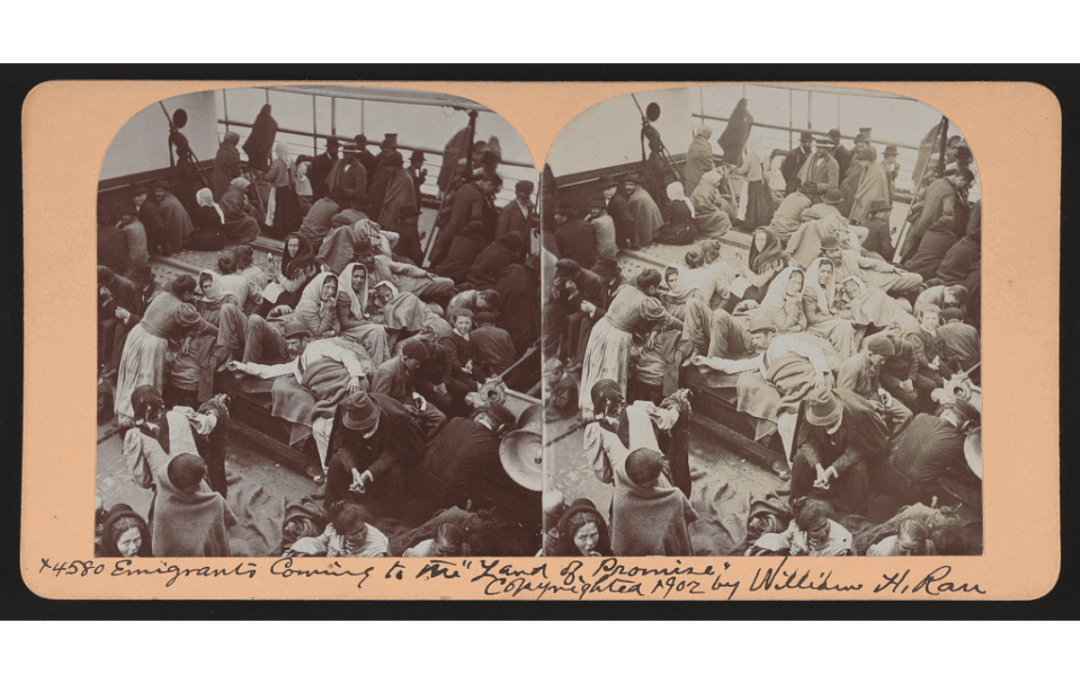

As for the photos, the internet is full of them now, and this is important. It truly matters that anthropological studies around Memory are finally gaining ground. Archives are being formed, long-forgotten materials are being donated, and universities across the world are taking up the torch; and this goes for our own institutions as well. From time to time, exhibitions emerge, often with great success, sounding the alarm bell. Take a look at the cover image: a large boat, sometime in the 1960s, practically yesterday, crammed with our own people, headed, most likely, for Australia. Unbelievable, and yet: isn’t the image almost identical to the overloaded boats of today, carrying the desperate migrants of the 21st century? Only the colour changes, ours were white. Sometimes not even that. This very photo was shown in an exhibition at the Teloglion Fine Arts Foundation of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

Or consider the villagers from Neo Chorio in Apokoronas, photographed in Utah in 1916 – they are the grandparents of my childhood friends! Or the Greek children adopted to a home in San Diego in 1956, as seen in Goda van Steen’s book Adoption, Memory and Cold War Greece: Kids Pro Quo? Or the Adontakis family, once again in Utah, back in 1908 – and what’s amazing is that we now shop at the store run by their grandchildren in Chania. The photo on the back cover? It’s a bundle of letters – the correspondence between one of my dearest friends and me. She was in America in the ’70s, studying mathematics; I was in Athens, studying law. The whole thing is a little like a game, a secret wave to people I hold dear. Only now, I’ve told you everything. Or almost everything. Thank you, truly.

___________________

Niki Troullinou was born in Chania and lives in Heraklion, Crete. A practicing lawyer, she has worked in education and rural tourism. Author of ten collections of short stories, two novels and small essays, she was shortlisted for the National Literary Award in 2024. Her publications, literature, criticism and travelogues have been published in a number of magazines and newspapers. Her literary texts have been translated into English, Italian, French, Spanish and Arabic. She is a member of the Hellenic Authors’ Society and Pen Greece.

Eleni Hall Manolaraki holds a degree in Classical Philology from the University of Crete and a PhD in Classics from Cornell University. She is an Associate Professor of Classics at the University of South Florida. Her publications in clude the book Noscendi Nilum Cupido: Imagining Egypt from Lucan to Philostratus (De Gruyter, 2013), as well as articles and book chapters on Roman authors. This is her first translation from Greek into English, a heartfelt gift to her homeland and mother tongue.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE