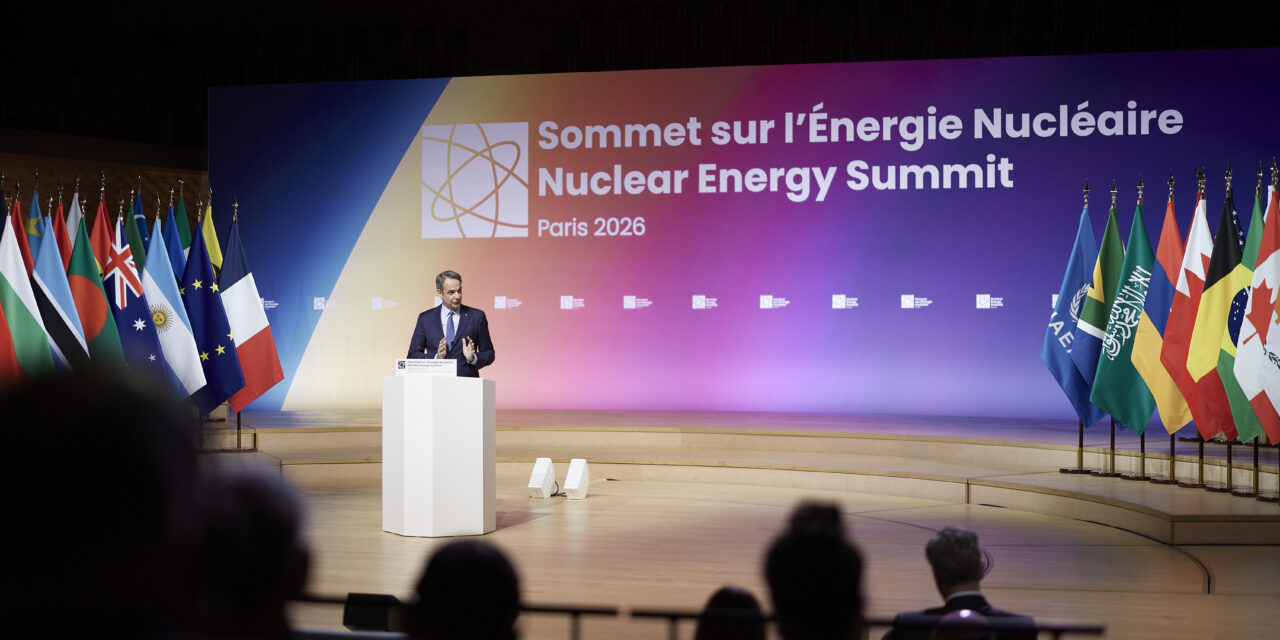

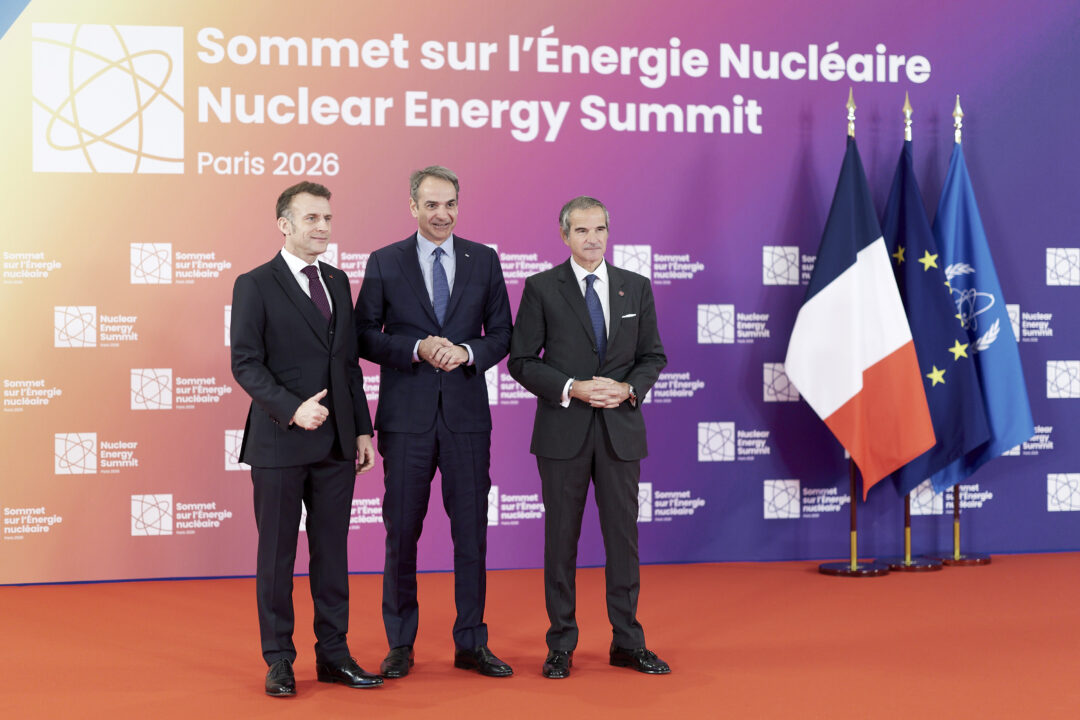

Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis participated in the 2nd Nuclear Energy Summit in Paris (10/3). At this summit — the second since 2024, when the first Summit was held in Brussels — 41 countries participated.

Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis stated in his speech, among other points:

“In Greece, in recent years, we have, invested heavily in renewables. Twenty years ago, we generated more than half of our electricity from coal. Today we generate more than half of our electricity from wind and solar. Renewables have turned us from a net electricity importer to a net electricity exporter. They have lowered our prices and strengthened our energy security. Given our superior resources, we will continue to invest in solar and wind, coupled with investments in batteries, pumped hydro and natural gas as a transitional fuel.

But the tide is turning. Nuclear energy is clearly having a comeback. Countries with nuclear power want to build more reactors and countries that abandoned nuclear power are reexamining their position. This is a welcome shift.

I came to Paris today to announce that Greece is also turning the page. It is time for my country to explore whether nuclear energy, and specifically small modular reactors, can play a role in the Greek energy system. We will set up a high-level ministerial committee to make a definite recommendation to the government on this front.

Our need for electricity is only going to grow. So no matter how much we expand renewables, we will need long-term predictable baseload power. No technology can match what nuclear can offer us.

Α topic that Greece cares a lot about is nuclear power in shipping. This is a proven technology that is already used for decades in military and other niche applications. At this point, we have no credible solutions to decarbonize shipping. Nuclear should be part of this conversation as well. It is a topic in which Greece plans to lead, separately from whether nuclear might have a role to play within Greece’s own system.

So, dear friends, this is a major day for Greece. We are writing a new chapter. Please consider Greece to be a friend of nuclear energy. Whether nuclear will end up playing a role in Greece remains to be seen. But at a time of great geopolitical upheaval, all options must be on the table. Our task is to make nuclear part of the solution again.”

(Source: https://www.primeminister.gr/en)

TAGS: ENERGY | GOVERNMENT & POLITICS | NUCLEAR