Emilios Solomou was born in Nicosia (1971). He studied History and Archaeology at the University of Athens. He also studied Journalism in Cyprus. He has been working as a journalist for a daily newspaper for some years. He is now a teacher of Greek and History in a public High School. Many of his short-stories were published in literary magazines and some were translated in English, Bulgarian, Polish and Turkish. His novels: Like a Sparrow, quickly you passed (2003), An axe in your hands (2007, Cyprus State Prize for Literature), Diary of an Infidelity (2012, E.U. Prize for Literature), Hatred is half a revenge (2015), The Scarecrow -a book for children- (2018). His novels were translated in many European languages.

Emilios Solomou spoke to Reading Greece* about the main themes his writings touch upon, noting that a recurrent topic in his books is “the drama of contemporary people, their loneliness while living in crowded cities and societies” and that he is also interested in “individual’s position and their weakness upon historical events”. Asked about the relation of literature to the world it inhabits, he comments that “consciousness is a factor that links literature to the real world”, adding that “fantasy is a mirror of reality that allows readers to exploit different ways of seeing the world”.

As for “Greek literature abroad”, he explains that “the main pursuit was to record the translators experience and form the contemporary picture of Greek literature abroad”, and points to “the absence of a well-organized network to promote and support the book in the host countries” and the “very limited number of translations worldwide related to Greek books” as major difficulties regarding the promotion of Greek literature abroad. “A two way collaboration between the production country, Greece, and the host country is required: continuous presence in international Book Fairs abroad, Greek cultural institutes, at least in important countries, active cultural attaché working for the embassies, closer synergies with the Departments of Hellenic Studies at Universities abroad, and of course a communication strategy, and an effective network for the promotion of Greek literature abroad”.

Your books have received quite favorable reviews upon publication while they have been translated in various languages. Which are the main themes your writings touch upon?

My first novel, Like a sparrow, quickly you passed (2003, self-published), deals with the life and death of my brother, who had been killed, with my first cousin, by a thunderbolt. An Axe in Your Hands (2007, Anef) is a story of a paranoid young man who destroys public statues in Athens, and he thinks that this world has gone bankrupt. He also believes he has discovered old maps and narratives about a new continent under Africa, Terra Australis. He even plans to get there with an old sail-boat and a bunch of vagabonds and children. The Diary of an Infidelity (2012, Psychogios) deals with the life of an archaeologist, professor at the University of Athens. While digging in Koufonisia, he excavates the remains of a pregnant woman, murdered 5000 years ago. During the excavation he cheated on his wife with a young student. Many years later this student, his new wife, would disappear unexpectedly leaving no traces. The archaeologist will return to Koufonisia, trying to find his balance between the past and the present in an effort to put his life in order.

Hatred is half of revenge (2015, Psychogios) is switching between presence and the 19th century. A young student captures a plan to murder the “Troikans” in Athens, on April 21st. Back in 1870, on 21st April another massacre took place, The Massacre in Dilesi, as it is known in History (a real incident). At that time, a group of brigands, Arvanitaki’s gang, slaughtered four foreign travellers, all important personalities. The public opinion in Europe turned against Greece in a very hostile way. The protagonist is a descendant of one of the brigands, of Cypriot in origin, who then managed to escape the persecution of the gendarmerie and the army. The book explores the relationship between then and today, the similarities, pathogens of the Greek state from its establishment (corruption, collaboration between politicians and brigands and economic interests). Finally, in the children’s book The Scarecrow (2018, Patakis) a scarecrow unexpectedly becomes human, acts and feels like a human. But people will consider it a demon. The book has to do with friendship, love and tolerance towards the difference.

A main topic concerning my books, is the drama of contemporary people, their loneliness while living in crowded cities and societies. This loneliness that increases as society modernises, is becoming more and more a stressful psychological factor that affects daily life. People find it hard to co-exist with the others. I am also interested in individual’s position and their weakness upon historical events, how ordinary people react and are crashed down under these often cataclysmic circumstances. Memory is also an essential part in my novels and short stories. Especially when memory as a metaphor, or image and experience, a trauma, as a snapshot and fragment, emerges and makes people deal with them in present. Past and present construct an interesting relation for literature. Memory and nostalgia give further depth to structure and characters.

“Writing as well as reading constitute forms and acts of communication as well as a means to move beyond the dead-ends of our era”. What is the relation of literature to the world it inhabits? How do the imaginary and the real interweave in your writings?

The relation of literature to the world is actually, in a way, the role of literature in general. Literature asserts the truth about what is happening, a different look on the reality we are familiar with. But let’s just confine it to one aspect, its social function. Literature examines the issues of real life and the world around us, good or bad. It’s like watching one’s own life embodied by other characters. Therefore, social consciousness is a factor that links literature to the real world. Imagination is a way, a slanted look, the means to go much further and understand, closely in depth, the world around us. It is a key element in literature. Authors construct their own reality and this reality is often invented. An author is subjected and influenced by his own biased perception of the world. And it is inevitable that even writing about reality, a part of imaginary will be used to form this reality. Fantasy is a mirror of reality that allows readers to exploit different ways of seeing the world.

In my case, I would say that imagination has a vital role. Imagination is an essential factor in keeping the balance with unbearable reality. Sometimes, while writing a book, in my excitement, I find it hard to say whether I, as a person, I’ m a part of imagination or reality, where fantasy stops and where reality begins. It’s like being one of the book characters. My first novel, is related to my brother’s true story. In many cases I have used magic realism as a technique to bridge reality with imagination. This fine line that divides imagination from reality, makes, I think, the story more interesting. An axe in your hands, was written more or less the same way and in the protagonist’ s eyes reality is distorted like a kaleidoscope. Imagination is constantly present, in the rest of my books, although the stories I am dealing with are much more connected to reality. What is most important in these novels is memory and the past that once existed as a reality.

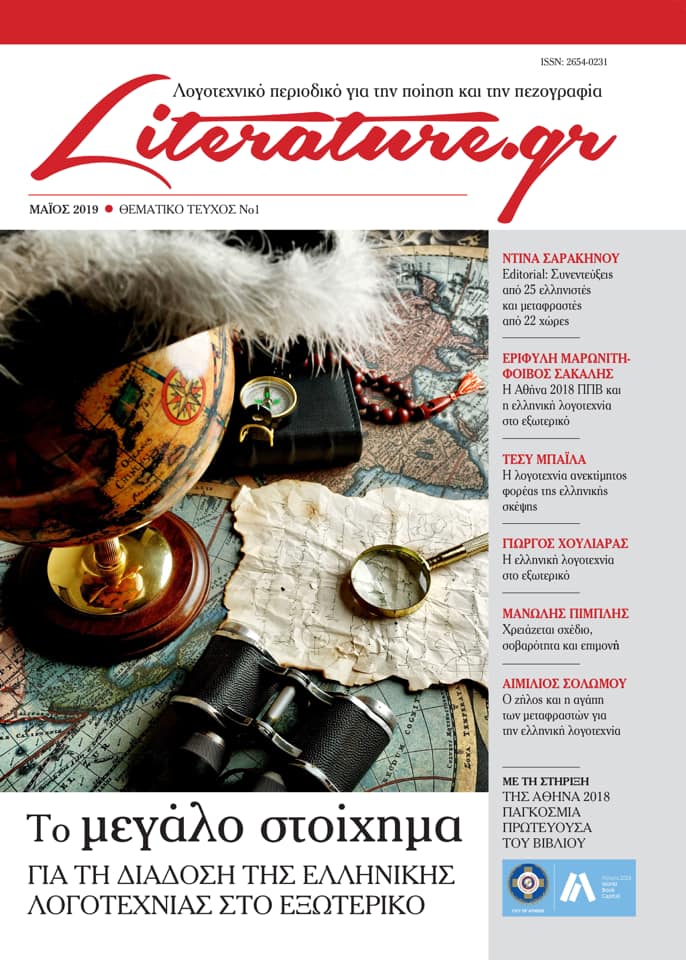

You are the editor of “Greek literature abroad”, a series of interviews with translators, which aims to delve into how things stand vis-à-vis the prospects and challenges of Greek literature abroad. Tell us a few things about this venture of yours.

The idea for the series of interviews with translators of Greek literature emerged while I was in Poland. The translator Ewa Szyler told me that she had a letter from Costas Tachtsis regarding his novel Third Wedding. Back in 1988 she was translating the book in Polish and she had some questions. Waiting for the author’s reply, she was informed that he had been murdered. But after a few days, she received his letter. “It was like a respond from the other world”, she said. So, I thought it was a good idea to record all these experiences. Furthermore, this idea was later strengthened when I was in Germany talking to the translator Michaela Prinzinger. She expressed her disappointment because translators and their work are not well appreciated as they should. So, the idea was formed. The main pursuit was to record the translators experience and form the contemporary picture of the Greek literature abroad.

The Greek literature abroad (1 Sept. 2017-4 Oct. 2018) includes 21 interviews with 28 translators (https://www.literature.gr/fakelos-i-elliniki-logotechnia-sto-exoteriko-2017/): Michaela Prinzinger (Gernany), Ewa Szyler (Poland), Klarisa Jovanovic (Slovenia), Maurizio de Rosa (Iταλία), Pavlína Šípová (Czech Republic), Christos Pulas (Albania), Elena Lazar (Romania), Damla Demirözü (Turkey), Natalia Moreleon (Mexico), Jan Henrik Swahn και Rea-Ann Margarita Melberg (Sweden), Dionisis Maroulis, Xenia Klimova, Lidia Ardanova, Pavel Zarutskiy, Catherine Basova, Irina Tresorukova (Russia), Jingjing Hu (China), Zdravka Mihaylova (Bulgaria), Stahis Gourgouris (USA), Anne-Laure Brisac (France), Fernanda Lemos de Lima (Brazil), Riikka Pulkkinen (Finland), Tamara Kostic-Pahnoglu (Serbia), Irene Noel-Baker (Britain), Khaled Raοuf (Egypt), Mario Dominguez Parra, Pedro Olalla Gonzalez de la Vega (Spain).

In a conference recently organized by literature.gr on the present and future of Greek literature abroad, the lack of a translations funding program as well as the lack of support on the part of Greek publishers were highlighted as the main difficulties for the promotion of Greek literature abroad. In this respect, which do you consider to be the prospects ahead for Greek literature outside national borders?

The one day conference was organized by Literature.gr as part of Athens 2018 World Book Capital project, whose major donor is Stavros Niarchos Foundation, and was held in Serafio Athletic & Cultural Center of the municipality of Athens, on Friday 8th of March 2019. For the first time 25 translators and Hellenists from 22 countries from around the world participated and shared their opinion on this topic. Also, the conclusions of the conference were presented in the 16th Thessaloniki International Book Fair. In order to contribute to this effort, a printed issue entitled ‘Literature.gr: The present and future of Greek Literature abroad’, which includes the conclusions of the one day conference, the interviews of the Hellenists and the translators plus the opinions of the speakers, will be sent to the Greek relevant authorities. The two reasons you mentioned are part of a wider chain of difficulties. For instance, the absence of a well-organized network to promote and support the book in the host countries.

We have to keep in mind that only a very limited number of translations worldwide is related to Greek books. For example, in England only 2-3% of the book production is connected to translation and the percentage regarding Greek books is extremely low. Let us not invest in great expectations. But we owe to be optimistic. There are reasons and positive factors for new perspectives. A new Institution is about to be established again succeeding EKEBI. At least it was promised by the government. During the past few years, in many countries new publishing houses have been appeared, publishing houses that are specialized or have a special interest in Greek books: Omonia (Romania), Poland (Ksiazkowe Klimaty), Albania (Toena, Neraida), Germany (Romiosini), France (Kambourakis, Quidam, Miel des anges) etc. There is also another factor that we have to invest in to fulfill these new perspectives. There are languages, spoken by hundreds of million and billion of people, that only a handful of Greek books were translated into, like Portuguese, Arabian, Indian languages and Chinese. These are huge markets and it’s about time to make a step forward, to grab the opportunities.

It has been argued that the Greece, contrary to other countries, does not have a ‘national literature’ with specific traits that would enable foreign readers to identify with it. Yet, wouldn’t such literature end up being outdated and folklore?

If we are referring to a national literature in the sense of brand name, yes our literature is not distinguishable to foreign readers. Foreign readers may know the works of Kazantzakis. However, they are not so familiar with Greek literature. But there are, in my view, characteristics that could form an identity for Greek literature abroad. Such could be the particular value of the Greek language and its relation to the European languages, the space and time in which the Greek books are situated, the special atmosphere, the modern Greek way of living, idiosyncrasy and mentality. One could mention the example of Petros Markaris, who has managed to create a personal brand. Other “minor” literatures have succeeded in creating a recognizable brand, like Scandinavian literature, the literature of Israel or Portugal, just to mention some examples. In any case, the foreign reader must have the impression when dealing with a Greek book that is something important, which has its own identity that distinguishes it from the other books on the bookshelves of a bookstore. The Greek book must inspire confidence, even to recall memories or something familiar. A relationship of trust must be built. To achieve this, a special communication strategy is needed, as well as marketing and public relations, in order to establish collaborative networks and have a long-lasting insistence regarding the promotion of the Greek book.

At the same time, we have to be careful while building an identity, a brand for the Greek book, to avoid the risk to slide into folklore. Especially because of the Greek past and the important role tradition values in contemporary Greek life and art. The answer is good quality literature, as Pedro Olalla said (in the series of interviews) on the question of what is needed to make Greek literature known abroad, “First of all, the obvious, quality books”. Good literature is written in Greece, and in this literature we have to invest in.

It is common knowledge that what the Greek book market lacks is a concrete and purposeful state book policy. What should be done at an institutional policy level for the promotion of Greek books abroad?

Above all, as it was emphasized during the Conference, it is necessary to reconstruct and establish the new organization the government has promised, an improved version of EKEBI (which indeed offered so much in the past and the decision to be closed was incomprehensible). A program similar to FRASIS for translation subsidies is also important, as well as the strengthening of Institutions that offer opportunities for learning modern Greek language to foreign scholars and specialized translation workshops. Furthermore, a two way collaboration between the production country, Greece, and the host country is required: continuous presence in international Book Fairs abroad, Greek cultural institutes, at least in important countries, active cultural attaché working for the embassies, closer synergies with the Departments of Hellenic Studies at Universities abroad, and of course a communication strategy, and an effective network for the promotion of Greek literature abroad. Additional to all these, is to draw up and implement a long-running plan, taking into account all these factors and the special characteristics of the market in the host country.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE