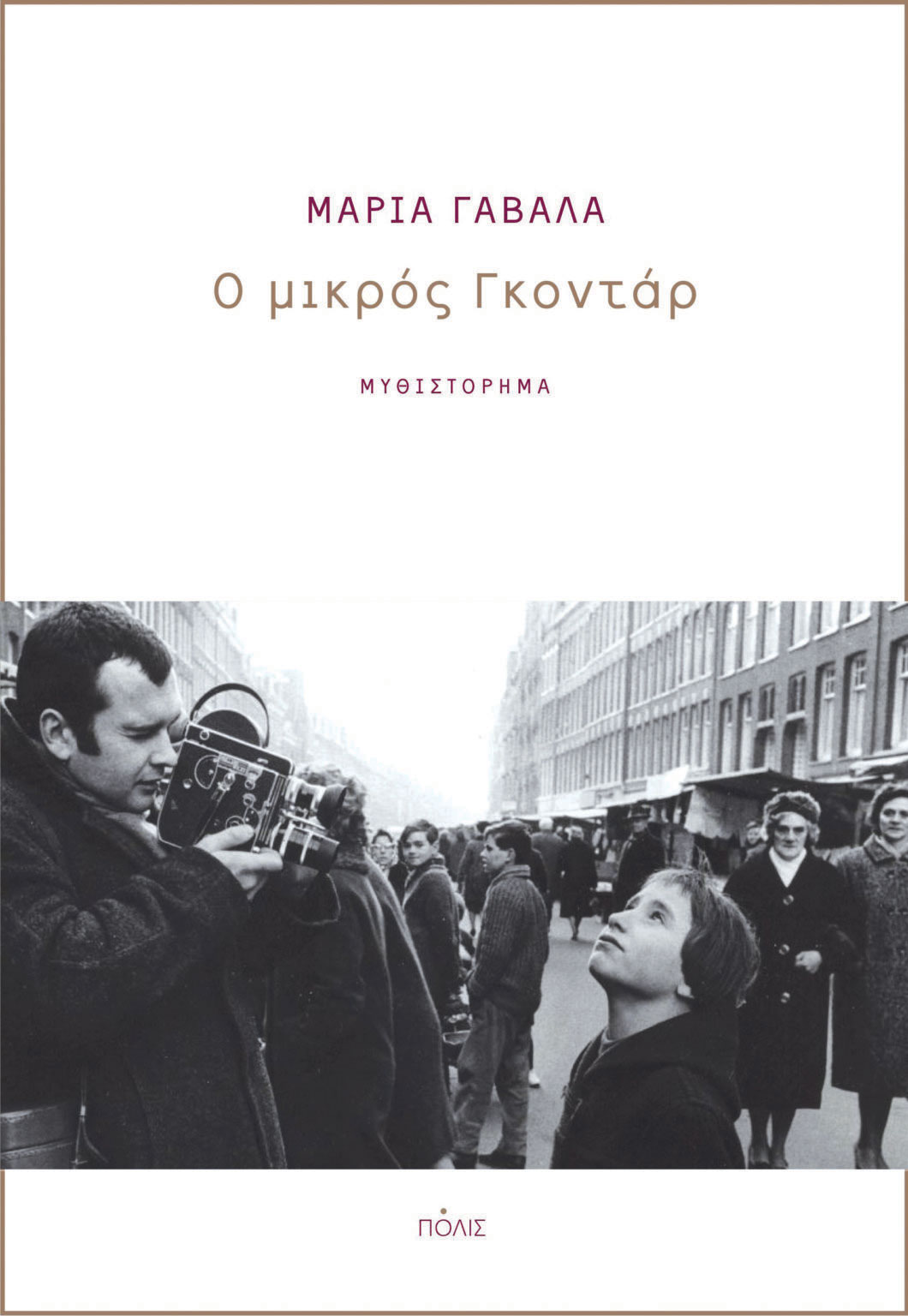

Maria Gavala was born in 1947 in Koropi, Attica. She studied history and archaeology at the University of Athens. She directed a number of cinema movies, wrote reviews on the cinema, and translated theoretical-cinematic as well as literary texts. Her new, ninth, novel titled Ο μικρός Γκοντάρ [Little Godard] was published by Polis in 2022.

Your latest writing venture Little Godard was recently published by Polis. Tell us a few things about the book.

It is a love story, between a young French filmmaker (Gaspar Frenel) and his Greek girlfriend (Lukia Vakari), the storyteller, who is studying cinema in Paris. At the same time, it is a reflection on the cinema itself, especially the documentary. A direct cinema, what is called cinema-vérité. Gaspar Frenel’s lens focuses on the May ’68 uprisings, the mass protests over the genocide of the Biafra people, the massacre of Algerian protesters in Paris in October ’61, the violent Islamizations in Africa, transatlantic slave trade, the consequences of the coup of the colonels in Greece. On her part, the story teller is a person that moves between two countries, Greece and France, as well as between two worlds. In Paris she has her studies and her love, in Greece she is attracted by her origin, the interest for her family and the painful adventure of her uncle who is a prisoner of the military regime.

Α very interesting element in Little Godard is the relationship between the camera and the “truth”. How is this issue approached in the book? How is your personal active involvement in the cinema imprinted on the way Gaspar attempts to capture the historical moment through his cinematic lens?

My hero follows a straight line of action, a frontal attack; he wants to film the events while they are happening, to the extent possible. His associates accuse him of not covering his bases, of not manoeuvring, of cunning, of not deceiving the authorities as he should. His straightforwardness is not good for him. Both Gaspar and his girlfriend also attach great importance to the events that have already happened, to the testimonies of people who experienced them first hand, who saw with their own eyes, who witnessed the dramatic events in their full detail. They are the only indisputable witnesses (I know well from my own cinematic experience, what an advantage it is for the eyewitness to be willing to become an “accomplice” of the cinematographer). However, it is often the case that these witnesses either disappear (usually against their will) or are practically difficult to find due to their relocation, death, or reluctancy to speak for various personal reasons. There is also the case of censorship from the above, of state control (I was personally a victim of censorship of my work, during the dictatorship in Greece, where the search for the truth was translated by the censors as “οbscurantism”) that prevents the capture of the truth, by destroying existing documents.

Just like in the novel, when the Algerian authorities destroy the negative of Gaspar’s film, throwing it in caustic acid. Then, people who investigate, cinematically, the truth must find new ways to prove what really happened. The search continues, persistently and painfully, despite defeats and disappointments. That is why it is often argued that the cinema, like any other means of capturing reality, does not always manage to convey the whole truth, but only part of it. Probably by delving into the root cause or by looking for related sources, an assistance from the official History and the course of things themselves, one could hope for a satisfactory result.

In his review of the book, Manos Kontoleon commented that a major trait in your writing are the cinematic descriptions of the urban environment. Where does the cinematographer meet the writer in your work?

As a filmmaker, I always did an exhaustive location scouting, searching and researching places before filming. The right choice of the places where a film will be shot is what is required. As a writer, I make sure to know well, up close, the places (urban or non-urban environment) that will star in my story (the city, the river, the plain, the metropolis, the degraded suburbs, etc.). There are several meeting points in the working methods of the cinema and literature, and one of them is to know exactly where you place the story you intend to narrate. Even if your setting is fictional or imaginary, you have to build upon it so that it seems real and convincing. Archive photos are more than helpful in case the spaces have changed, in terms of construction, over time. A photo of a past era, published in an old newspaper, often saves the day.

Since your first novel in 1994 till today, almost thirty years later, what has changed and what has remained the same in your writing? Αre there recurrent points of reference in your books?

Strange as it may seem, I reckon I have always worked around the same idea from the beginning of my career both as a filmmaker and as a writer. Everything revolves around a person who is persistently looking for something that is not always clear. It may be a clue, a question, that will help the “self” to console itself, that will alleviate its mourning for the various losses.

How does literature relate to the world it inhabits? Where does the personal meet the collective in your work?

The world around us influences our work, even if its starting point, its architecture or its logic are completely imaginary. Experiences guide our steps, while gender constitutes a seal. I believe that the personal imperatively seeks the collective. The two may not be identical, yet the one approaches the other, and together they can offer a kind of relief. A person puts aside his selfishness and opens to the care and love for another, which means the end of isolation and loneliness.

What role is Art called to play in times of crisis? Could it be used to soothe fears or rather to prompt to action?

That’s a major issue and whatever answer needs to be further explained. I reckon that it all depends on the human character, people’s mentality and experiences. Some console themselves with Art, not necessarily in a passive way, while others use it a weapon to mobilize and act. It is a matter of talent, ability, courage, will, discipline and endurance above all.

How would you comment on current literary production? Could literature be used to consider what could be radically different realities?

This would be ideal, to get acquainted with the differences, approaching them within the framework of current literary production, but also within literature as a whole and over time. Delving into identities and particularities. Aiming at convergence where needed and when possible. Inevitably, there are different realities on the planet. Things take a different course in the various parts of the world. Evil lies in authoritarianism, intolerance and bigotry. Such phenomena are above and beyond Art. If you visit a world art exhibition or read literature, or watch music, you will find that there are obvious differences among works from different parts of the world and alas, if these differences didn’t exist.

On the other hand, there are equally self-evident common points: the fear of death, the desire for a smooth continuation of life, the impossibility of freedom, its need, poverty, obstacles of all kinds, the restraints imposed by the strong on the weak, all sorts of radicalizations, dilemmas and problems that people are called to face and solve, not always successfully, and so on. It would simply be romantic or naïve or hypocritic to argue that the fate of people is the same everywhere. Deadlocks exist. And we don’t really know how gaps are bridged or how wounds are healed. Art doesn’t have ready answers for everything. Nor can it be considered a shelter or a crutch. Unfortunately, the future is far from clear. We have to try hard, not only vis-à-vis the art of ‘writing’, of ‘language’ and communication, but also vis-à-vis the art of survival. As for the art of living, for many parts of the world it remains an unsolved puzzle or an elusive dream.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE