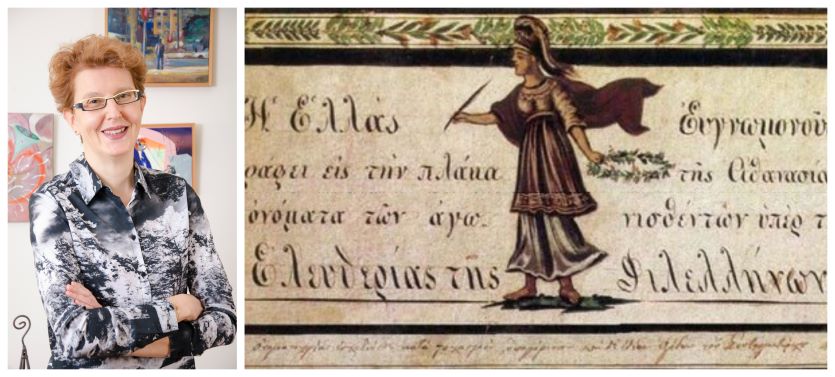

Anna Karakatsouli is Associate Professor of European History, at the Department of Theatre Studies of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. She has been an Expert Associate in the project of the new edition of the History of Humankind by UNESCO and Vice-director at the Alexander S. Onassis Foundation. Her research interests include intellectual history, history of colonialism and history of the book. Among her more recent publications are ‘Freedom Fighters and 1821: A Transnational Approach of e Greek War of Independence’ (2020, in Greek) and ‘In the Land of Books: The Publishing History of Hestia Publishers and Booksellers, 1885-2010’ (2011, in Greek).

Anna Karakatsouli spoke to Rethinking Greece* about the transnational aspects of the 1821 Greek War of Independence; the varying identities and motivations -from romantic ideologues to professional soldiers- of the Philhellenes, those ‘freedom fighters’ of the 19th century who left their countries to fight for Greek Independence, their interactions with rebellious Greeks, their impact on the outcome of the Greek Revolution and their participation in liberation movements around the world, as part of a ‘Liberal International’. Last but not least, Karakatsouli introduces us to a largely unknown literary work, Mary Shelley’s book, “The Last Man” a futuristic gothic novel using as backdrop setting the Greek War of Independence, still being fought in the 21th century.

Eric Hobsbawm has written about the “Liberal International” of the 19th century. In your book, “Freedom Fighters and 1821”, you include the Greek Revolution of 1821 in the great revolutionary wave that manifested itself in Restoration Europe and in the Latin American Wars of Independence. Can you tell us more?

The Greek Revolution of 1821 erupts at a time when the principles of the Congress of Vienna have been imposed on Europe and the will of the Holy Alliance rules. After the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815 and the restoration of the legitimate royal dynasties to their thrones, the French Revolution was considered an unfortunate interval and liberal ideas and their supporters were persecuted throughout Europe. The implementation of the authoritarian policies of the Holy Alliance of Russia, Austria and Prussia, was met with many reactions, and the most intense attempts to shake off this conservative grid of power took place in the Mediterranean countries of Spain and Italy in 1820. At the same time, the wars of the peoples of Latin America for their independence from the colonial rule of the old empires of the Iberian Peninsula were being fought. I believe, therefore, that we can gain a wider and deeper understanding of the Greek uprising against Ottoman rule -which followed a few months later- if, instead of treating it as a single national revolution, we include it in this wave of European and South American liberal claims.

The exact number of volunteer “freedom fighters” who arrived in Greece, or the Philhellenes as they are widely known, is eluding us. The most recent calculation was made by historian Hervé Mazurel, who, after a comparative review of the data by several sources (published statements of the fallen, references in various memoirs, police reports, etc.), points out the serious problems of this project, such as the difficulty in identifying frequently Hellenized names or their correct spelling. What is more, in older headcounts, a rather expansive definition of the concept of Philhellene was used, including lists of the military personnel of the Great Powers stationed in the area, such as the three admirals, De Rigny, Codrington and Heyden, who took part in the Battle of Navarino, or the French officers of Maison’s expeditionary corps in Morea, in 1828. After the necessary data clearance, Mazurel finally comes to the number of about 1200 people in total, whom he divides by nationality as follows: Germans 36%, French 21%, Italians 14%, British (including Irish and Scots) 10% -which means 81% of the total belong to these four nationalities.

These foreign fighters arrive in Greece in three waves, corresponding to the three different phases of the philhellenic movement. They are people who moved at the political margins of their home countries, such as Irish and Scottish radicals from Great Britain, Bonapartists from France, liberal nationalists from Germany, for all of whom the Mediterranean revolutions were a way out of their disappointment in their respective countries’ domestic politics. The first wave began to come in a spontaneous and improvised way as soon as the news of the Greek uprising spread to the West. Most of them were young men, demobilized conscripts after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, romantic students in search of adventure, lovers of the classical spirit, vagarious wanderers, or frustrated adherents of the French Revolution. They boarded ships at Trieste and Ancona and disembarked on the shores of the Peloponnese, where they were met with a chaotic situation, which was very different from what they expected, and with a complete lack of logistic support on the part of the warring Greeks for their reception and integration in the armed forces. Among those first to come to the aid of Greeks were the warriors of the Battalion of the Philhellenes who were decimated at the Battle of Peta in July 1822. Many of those who survived returned to their homelands and conveyed their painful experience of Greece in articles and books, so as to dissuade others from embarking on such an adventure.

The second wave of Philhellenes was motivated by the news of Lord Byron’s death in Missolonghi in April 1824. Byron was an idol for romantic souls everywhere; his death placed him in the pantheon of heroes and rekindled European public interest in the Greek cause after the negative impressions that had dampened the initial enthusiasm for Greece. More importantly perhaps, Byron’s death coincided with the suppression of the uprisings in Spain and Portugal. After the intervention of the French troops in the Iberian Peninsula and the restoration of the royal dynasties to their thrones, the Greek case was the only remaining refuge in Europe for persecuted revolutionaries. The key difference from the first wave is that the volunteers of the second phase were experienced officers, with a long career in the Napoleonic Wars, several of them conscious democrats, but there was no lack of adventurers / mercenaries of the revolution who negotiated hard in exchange for their participation. Among the most famous are the Frenchman Charles Nicolas Fabvier, the British Thomas Cochrane and Sir Richard Church or the Italian aristocrats Alerino Palma, Giuseppe Pecchio and Santorre di Santa Rosa.

Finally, the third and last wave of Philhellenes of the years 1827-1828 has a completely different character. It is essentially the first humanitarian aid mission in modern history and is mainly the result of transatlantic initiatives of private US philhellenic committees to collect clothing, medicine and food. These supplies, distributed by the Americans themselves to Greek civilians, averted the risk of famine in the war-torn country.

What role did the Romantic movement and classical education play in the decision of the Philhellenes to come to Greece? Were there other motives, besides the liberal ideals of the time and admiration for ancient Greece?

Romanticism is a movement with multiple, often contradictory motivations and currents, simultaneously (or alternatively) revolutionary and counter-revolutionary, individualistic and communitarian, cosmopolitan and nationalistic, realistic and imaginary, backward-looking and utopian, rebellious and melancholic, democratic and monarchical, red and white, mystical and sensual, as Michael Löwy put it. As a movement for the liberation of artistic creation from the strict norms of classicism, emphasizing the personal and direct expression of the artist’s feeling and sensibility, it embraced the uprising of the Greeks from the very beginning. A genuine and daring national struggle in the Ottoman East, far away from the core of industrial Europe, which gave voice to an oppressed Christian people, the Greek cause constituted an ideal source of inspiration for high-brow visual, poetic, musical and theatrical works. The fact that this particular struggle was located at the birthplace of classical culture, which had already been recognized as the foundation of European culture, further propelled Greek issues to the forefront the public and artistic interest in the West.

However, we must mention two other important motives that explain the mass mobilization on the side of the warring Greeks. The first is the impact of the idea of freedom in an era of authoritarianism and oppression, which transcended national boundaries, and created this dynamic cosmopolitan movement that is philhellenism. The second is more personal and concerns the acute problem of economic survival and professional career faced by the numerous officers who were demobilized on half pay en masse after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, in 1815. The high cost of living and their exclusion from state European armies led them to seek the continuation of their military careers on foreign fronts, such as Latin America or Greece. This creates the informal “Liberal International” –firstly identified as such by Eric Hobsbawm- which unites liberal army officers from all over Europe into a wandering group with similar experiences and a common ideology.

Many of the philhellenes who came in Greece to fight were disappointed by the situation they encountered there. In your book, you point out that this is due to objective difficulties linked to cultural differences, but also to a paternalistic / colonial view of the Greeks. Can you tell us more?

In the Revolution of 1821, the Greeks and the Philhellenes were two coexisting but very different groups: they had incompatible goals, diverging political, social and cultural references. As it turned out, the preconditions of an honest exchange and cooperation were not there. It is therefore not surprising that the communication channel between Greeks and Philhellenes ultimately did not work.

On the one hand, you had foreign volunteers who served ideologies of the West -such as Jeremy Bentham’s liberalism in the beginning, or socialist Saint-Simonianism later on-, their country’s political plans -like the House of Orléans’ and the Bavarians’ aspirations for the Greek throne-, and / or their personal pursuits for military distinction and recognition. On the other hand, you had the rebellious Greeks with their vision of national independence that overlooked any western projections and ideological constructions, and willingly made use of all the advantages that could be derived from western participation in the Struggle. In the Greek case, we do not have the formal political-economic subjugation and colonial bureaucratic mechanism presupposed in Edward Said’s concept of Orientalism, but a paternalistic and disparaging discourse does dominate the texts of the Philhellenes fighters, defining an environment that is not colonial, but neither is it recognized as European.

What was the contribution of Philhellenism to the outcome of the Greek Revolution? What is more helpful on the military or on the political / diplomatic field?

A permanent point of contention and friction between the foreign volunteers and the rebellious Greeks was the way the war was conducted, and especially the radical deviation of Greek guerrilla war tactics from western battle standards. The foreign “freedom fighters”, on a cosmopolitan life trajectory, had reached the south-eastern Mediterranean committed to the ideal of freedom and faithful to their personal conception of military honour, war ethic and glorious career. The collision with the reality of the battlefield proved insurmountable, and the two worlds moved in different orbits. The Philhellenes tried but failed to persuade the Greeks to follow their own military culture. What they couldn’t see was that their western way of fighting was as much an expression of their culture as the Greek kleftes and warlords’ “live today to fight tomorrow” tactic.

The foreign volunteers gave the battle of civilization against barbarism, only often the modern Greeks were included in the second camp… What is more, all attempts to use two incompatible troops -the regular formation of the Philhellenes and the guerrilla Greek groups- in a single battle order, systematically ended in defeat. Consequently, we place the positive contribution of the Philhellenes not in the military field but rather in that of public awareness: for Greece the benefit from the constant presence of foreign fighters was mainly that of keeping the Greek Struggle in the international agenda for a surprisingly long time and ensuring the uninterrupted interest of public opinion, until developments in European political and diplomatic relations created the favourable climate that would allow the establishment of an independent Greek state.

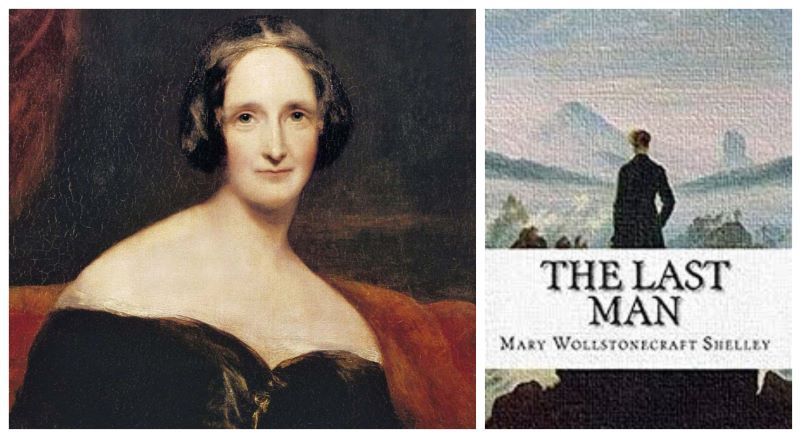

In the epilogue of you book “Freedom Fighters and 1821″ you refer to Mary Shelley’s book, “The Last Man” a futuristic work using as a backdrop setting the Greek War of Independence, which continues until 2100…! I think few of us are aware of the existence of this very interesting combination of romantic fantasy and philhellenism, can you tell us more about it?

Mary Shelley is best known for her first work, “Frankenstein or Modern Prometheus” (1818), and she is an excellent case study of early female emancipation. As the wife of the great romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, she moved in European philhellenic circles, befriended Alexandros Mavrokordatos and participated in the political and ideological developments around the so-called “Pisa Circle”, revolving around Byron and Shelley. “The Last Man” is a fascinating, extensive, and multi-faceted gothic novel written in 1824, when Mary Shelley returned to England. Published anonymously in 1826, it is a futuristic dystopia set in the late 21st century: conflict in the Balkans is not over and the Greek army is besieging Constantinople under the leadership of a British general who we can easily identify as Byron. The Greek forces conquer the city but are infected by a plague; the epidemic then spreads around the world killing everyone on Earth except the titular Last Man. Instead of the expected glorious “Hellenization” of Constantinople, we are led to the slow infection of the western world by an eastern plague.

Shelley is inspired by the Greek case and eloquently describes recognizable scenes from the Greek Struggle for Independence, such as the fall of Tripoli or Ottoman Athens. Moreover, her work contains very bold and original thoughts on the political regime of Great Britain; this critique, especially coming from a woman, probably annoyed the critics of her time, who judged the novel very harshly with deprecating, gendered characterizations. As a result, the book was republished only once in England and once in Paris, both in 1826, and published without licence in the USA in 1833, to fall into obscurity afterwards. The Last Man came back to the fore only in the mid-1960s, with the development of gender and postcolonial studies in Anglo-American universities, which highlighted the richness of his references and the multiplicity of his meanings. Its translation into Greek came very late, in 2008, and is now out of print. However, readers can look for the original text, which is freely available online: https://freeditorial.com/en/books/the-last-man

What would a modern version of philhellenism entail?

I see philhellenism as a moment of international solidarity of peoples in the common struggle for freedom. In the early 19th century, the peoples of Europe were trapped in authoritarian multinational empires, where ethnic minorities (e.g. Greeks in the Ottoman Empire, but also Italians in the Hapsburg Empire or Poles in the Russian one) lived in a state of fear, oppression and exploitation. The strength of the philhellenic movement and the massive support of international public opinion contributed significantly to the success of the Greek Revolution, and to the creation of an independent nation-state for the first time in the modern European history. In other words, they achieved the unthinkable!

Today we find ourselves in an environment of absolute globalization; the sovereignty of nation-states is receding rapidly in the face of the unhindered supremacy of the forces of international finance and supranational organizations, with painful consequences for their peoples. A modern version of philhellenism could therefore mean a new struggle for the unthinkable, and a new awareness of the power of peoples’ solidarity to defend freedom, social justice, and human dignity for all.

*Interview and translation by Ioulia Livaditi

TAGS: 1821 | GREEK WAR OF INDEPENDENCE | MODERN GREEK HISTORY | MODERN GREEK STUDIES | PHILHELLENISM