Atalanti Evripidou is a female speculative fiction writer from Greece. She also dabbles in poetry, on occasion, and is a social psychologist by profession. Her short stories have been published in various Greek anthologies and her work has been featured in Onyx Path’s “Gods & Monsters” and “Forgotten & Forbidden Orders”. More recently, her fiction has appeared in venues such as Luna Station Quarterly, Skull and Laurel, Star Maidens, and Gallery of Curiosities, among others. Her first short story collection in Greek, The ones that stayed behind (Polis Editions), came out in Autumn 2024 and was heavily inspired by Greek history and folklore.

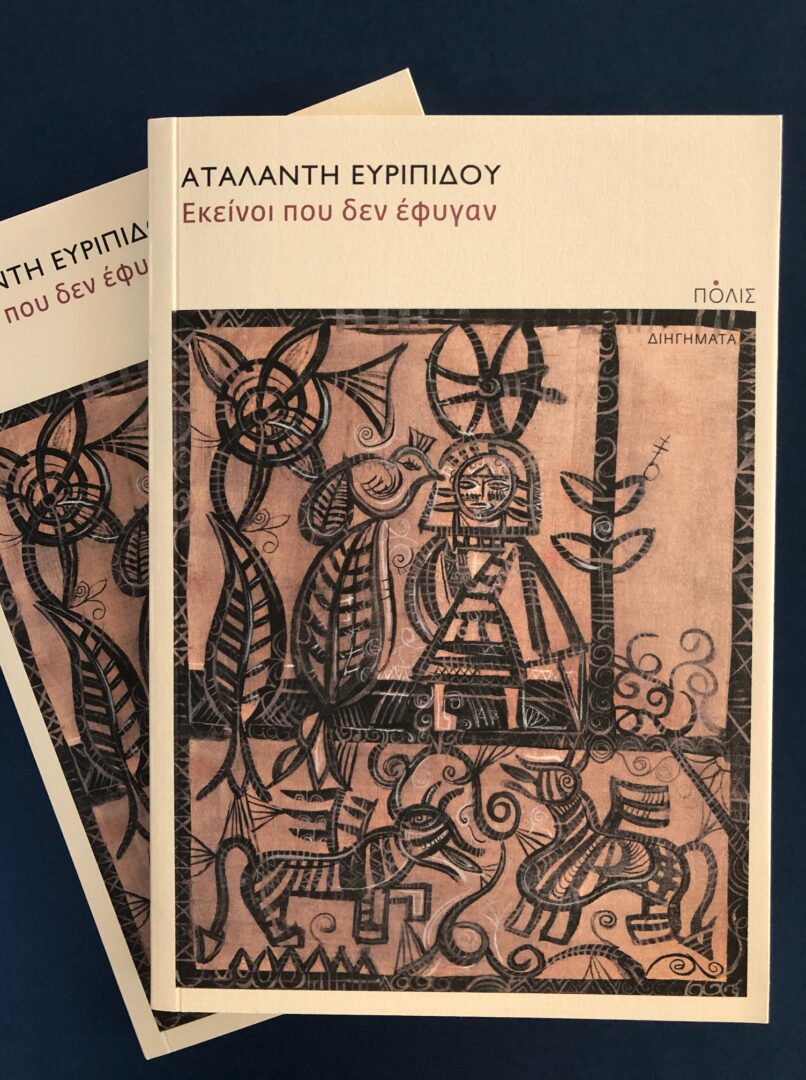

Your writing venture Εκείνοι που δεν έφυγαν [The ones that stayed behind] was published by Polis in 2024. Tell us a few things about the book.

The book is a collection of seven short stories spanning several centuries, from the early Ottoman regime (so, around the 15th or 16th century) to the present day. The stories paint a picture of a quasi-mythical Greece, filled with fairies, ogresses, semolina men, girls with hooves, and made-up husbands. They draw from Greek folk tales and songs to tell tales of people in the margins and the liminal spaces of the world; LGBTQAI+, sex workers, women, ethnic and religious minorities. As a whole, the collection aims to showcase how the world is slowly disenchanted and, at the same time, how important togetherness and acting collectively are in fighting against this disenchantment.

Your short stories chronicle people on the margins of history – women, queer people, ethnic and religious minorities – that were rarely visible, yet have always been present. How does literature converse with History in your book? Where does the History of the world meet the micro-stories of everyday people in your writings?

I think that, as an artist, the only way to treat History with respect is to approach it with empathy. And, to be empathetic, you need to focus on the human level. Looking at the greater picture is extremely important, of course, because it allows us to see the systemic and strategic reasons leading to each event. However, History isn’t something that happened to other people and was over and done; we still carry a lot of trans-generational and national trauma. We carry it, not our distant ancestors. And we must acknowledge that too. At the same time, so much of History has been lost. Uncovering the dismissed, destroyed and often hidden History of minorities has been an ongoing struggle for many social studies and humanities researchers. Therefore, art (and literature in particular) is a great way to re-imagine and re-create what has been forgotten, to give voice to those who have been left without their own. In the end, I think historians, anthropologists and sociologists have been doing an amazing job showing us the greater picture, the capital-H History. Us artists get to imagine how these events affected and shaped the everyday people left behind.

More generally, how does literature converse with the surrounding reality? Can literature be used to create what could be radically different realities?

For sure. Reimagining reality is what writers do best, particularly writers of speculative fiction: we speculate. We look at what is and consider what could be. I’ve always been of the opinion that what sets artists apart is that we’re able to see the wounds in the world and we’re filled with a deep need to heal them. We do that by sharing our vision of the reality, hoping that, if enough readers get it, we could actually change the world. Literature isn’t simply the telling of stories to achieve aesthetic pleasure. It is also an act of defiance and a challenge. An invitation, if you will, to consider and work towards a different reality – a better reality.

What about language? What role does language play in your work?

Language is extremely important to me. Going back to this short story collection, I tried to capture the changes in Greek language through space and time as best I could. Not only for authenticity, but for empathy as well. Engaging with a language or a dialect literally, scientifically, re-wires your brain and changes how you think. In addition to that, I also happen to be a huge poetry lover. So, rhythm, flow, sentence structure and musicality are all a huge part of my writing style. I can’t help but enjoy a prose that sings, so that’s what I strive for as well.

“Fantasy literature, like any genre, is a vehicle for talking about reality. We may write about fairies, vampires or robots, but at the bottom of it all, we are always writing about people”. Tell us more.

Well, we are; that is the truth of it. Speculative fiction is a wonderful tool to explore reality with, but let’s not forget that us writers live in the real world, where all the real things happen. So many hurtful, terrible things, and so many brilliant, wonderful things as well. We look at them, take inspiration from them and transform them into fantastical worlds and beings, epic stories and grand romances, fights against darkness or casual horrors. It doesn’t matter. In the end, what readers connect with are stories about people. Speculative fiction is often put under fire for being escapist, but that simply isn’t true. It can be, of course. For the most part, though, it’s simply a tool that allows us to pose our most burning questions and attempt to give somewhat adequate answers. And, at its core, isn’t that what all writers do? What all artists do?

How do contemporary Greek writers converse with global literary trends? Where does the local meet the universal in your writings?

Allow me to speak about writers of speculative fiction mainly, as that is my personal lane. We have phenomenal writers in Greece that have won prestigious awards and nominations for awards abroad, and many more that have been published in excellent, long-running magazines. Just to offer some names, Natalia Theodoridou, Evgenia Triantafyllou, Christine Lucas, Victor Pseftakis, Antonis Paschos, Dimitra Nikolaidou have been consistently publishing abroad for years. So have I. And because of this contact with the global market, our short stories in particular tend to differ in form and structure from the traditional Greek short story. However, it is a bittersweet success, considering that we had to look for it outside our country, writing in a language that is not our own. Speaking only for myself, I feel that this bittersweet state has allowed me to tap into those literary trends in an unexpected manner, considering that we seem to be experiencing a global identity crisis. Writing and getting published in English has pushed me to write something as deeply Greek as this book and, eventually, watch it get published.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE