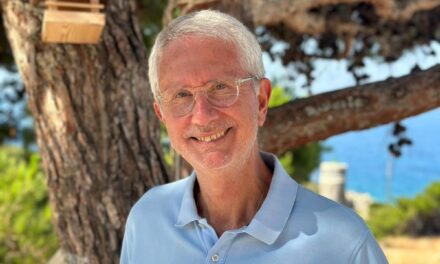

Giorgos Dritsas was born in 1994 in Corinth, Peloponnese. He graduated from the Department of Philosophy, Pedagogy and Psychology of the University of Athens, where he continued his postgraduate and doctoral studies. In 2016 he self-published the poetry collection The echo of Zarathustra, while the next two poetry collections with a common theme, Shadow of Death (2022) and Bloody Dream (2023), comprising old and new poems, were published by Odos Panos Publications. His poems and short stories have been published in online and print journals and anthologies.

You have published two poetry collections – Shadow of Death [first testament] followed by Bloody Dream [second testament] a year later – both by Odos Panos. Tell us a few things about the books and what binds them together.

First of all, I must say that these two books are part of a bigger corpus of poems, forming in this way an unofficial “dilogy”. The poems included were written over a period of 6 years and were chosen mainly for their related patterns. They were consistent with the meaning I wanted to communicate, which was mainly existential, with many elements of political and social criticism. In the beginning, I didn’t know if I wanted to publish them “officially” in a publishing house and this eventually came about, quite by chance, after the encouragement of poet George Chronas, who is the founder of the historical publishing house Odos Panos, where I finally published them.

Loss, an underlying melancholy, loneliness seem to permeate the poems in a world that seems hostile and disappointing? Does poetry constitute an escape from this gloom?

Yes, the truth is that there is an unwitting focus on these “dark” feelings inside the poems. My main purpose was to move myself into a creative form of expression and to describe all these different and very intense psychological feelings that I have experienced and continue to experience. Melancholy, loss and loneliness, after all, are mere cousins of depression and are thus very intense feelings as well. But despite this, when I express myself on paper it is like a great weight is lifted from my body, which helps me to better control any swings of my mood.

More generally, how does poetry converse with the world it inhabits? Does it constitute a way to imagine what could be radically different realities?

I believe that, in general, every society has a way to enter the imagination of each individual, and each individual respectively connects to and reinforces that imagination. Thus, imagination is a “new land” and a “new world” that is connected to our common world through the conscious and subconscious part of our perception of reality. Therefore, I believe that poetry creates new realities, because while being written, it often bypasses its own creator and becomes autonomous, as poet George Le Nonce has mentioned in “Manteio” in a bit different way. This is why sometimes such great disruptions of the “Being” of reality, that we are used to believing as the ultimate truth, are expressed and structured in poems, while new forms of “uncanny” realities are created inside them, acquiring completely new meanings – without necessarily leading to cerebral “ambiguities”.

Your academic background seems to have influenced your poetic writing? Where does philosophy meet poetry in your work?

I have been greatly influenced by my studies in philosophy at the University of Athens and by my Professors there. Generally speaking, I believe that philosophy and especially philosophical language is crucially linked to poetry and can influence it in great depth. After all, poetry, as mentioned above, constructs new realities, and through them shapes a theoretical basis that can lead to a new inspiration, which in turn helps create a new worldview and – why not? – a new vision of the world. It is no coincidence that many revolutionaries of the past were both philosophers and poets, while many philosophers and poets have become revolutionaries, which decisively shaped their world. More specifically, in my own books I try to make these connections clearer so that any philosophical references that I make are not lost in some kind of poetic lyricism, which is not connected to the poems nor has a poetic function by itself.

What about language? What role does language play in your writings?

Language, as a method of encoding images and meanings, is of great importance to me, especially when I write poetry. It somehow untangles these unstable dark clouds of words interwoven in my mind, giving them a certain form. You can say that words act as verbal “totems”, encapsulating in the external world something internal that could not be expressed in any other way; otherwise, it would get lost deep in my thoughts. For this reason, language is for me a constant revolution by itself, while poetry through the redefinition of the meanings of words constitutes an explosive material that leads to greater and better intensity, beyond formalization.

How contemporary Greek poets related to world literature? Where does the local/national meet the global and the universal?

I think that we live in a time where it is easy to read, in one or more languages, foreign poets, to be inspired by them or even to communicate with them. We are at a stage of the so-called Western civilization and more generally at a stage of the modern globalised world in which cultural osmosis is not necessarily something dubious or time-consuming as in the past, but something that is constantly taking place – especially because of the widespread use of the English language. So there is always this particular meeting of local/ethnic elements with the global web of the new literary trends of other countries, which I think is a positive thing as long as it is done creatively and not mimetically.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE