Dr. George (Yiorgos) Samoilis, originally from Greece, is a psychologist and university lecturer based in London. His literary career began with the publication of his debut novel by IntoBooks (Athens) in 2011. In 2018, he followed with a collection of psychotherapeutic short stories published by Odos Panos (Athens). His first poetry collection The Place Without Darkness was released in 2020, and his prose has been featured in the literary magazine Odos Panos. In 2021, he received the Finalist and Honourable Mention Poetry Award from Società Dante Alighieri in Rome. His second poetry collection, The Leaves (and Letters), was published in 2023 by Thraka Publications in Larissa, Greece. In 2025, he contributed to Versopolis’s Poetry Expo 25 with the works Potentialities of Love and Normalcy.

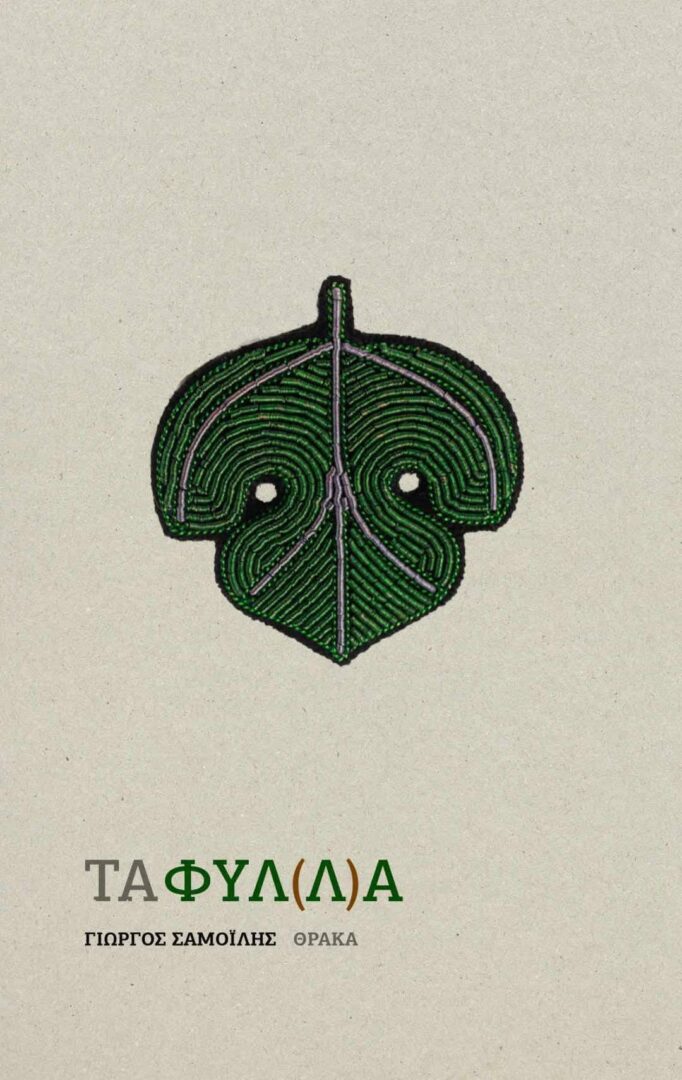

Your second poetry collection is titled Ta φύ(λ)λα (Thraka, 2023). Tell us a few things about the book and its title.

The title is essentially a play/dialogue between the words “gender” (fýlo) and “leaf” (fýllo), perhaps even a small neologism. My intention, as in some of the poems, was to use language allegorically and to intertwine environmental issues with themes of gender identity. I consider both issues to be of utmost importance in the current international socio-political climate, given the ecological crisis of the planet and the global resurgence of conservatism and far-right rhetoric regarding gender identity, human rights, and beyond. In this sense, the whole collection addresses vulnerable populations and themes such as the environment, migration and displacement, as well as gender identity and the self in a rather psychological sense. If the collection were a painting, the frame would be the international socio-political situation as I perceive it, and the painting itself would be represented through all these themes.

Τhe book seems to interweave personal micro-stories set against the contemporary socio-cultural reality. Where does the personal meet the collective in your work?

It is inevitable that the personal becomes embedded in my writing. I write from a place of subjectivity, my understanding of myself, the world, and those around me. I am both embodied and embedded, an Aristotelian social animal. Therefore, in my work, the personal cannot escape its encounter with the social and the cultural. For me, the creation of a poem entails a moment of encounter: my perceptual system takes something in-let’s say an object-and, through the construction of language and the use of imagination, transforms it into something different (sometimes beyond the conventional or the normative). In addition, as a social being, I am also a by-product of the collective, situated at this particular point in time and place. Thus, the personal, the cultural, and the sociological all come together to form a dish, a kind of soup, as I like to think of it composed of many ingredients thrown into a pot, my brain. I am not certain whether the dish is entirely edible, but I have done my best to stir its contents at the time when this collection was written.

What about the political aspects of gender and their revolutionary potential in literature?

I am not entirely sure. With the fourth industrial revolution underway, in an era of post-truth and late capitalism marked by far-right politics, the commodification of identities, and a clear necropolitical agenda in full swing, I struggle to see much genuine revolutionary potential in literature when it comes to gender. You may say I am a pessimist; I consider myself a critical realist. The world, as it stands, is a deeply traumatic and traumatising place, even more so for gender non-conforming individuals. Still, I hold onto a spark of hope, though it must be ignited collectively. This is where politics, in my view, are failing LGBTQI+ people: through divide-and-conquer strategies that lead to alienation, fragmentation, segregation even conflict.

This is not to minimise the importance of artistic and poetic works of high calibre. But let me give you an example to illustrate my point. Imagine, for instance, the lived experience of an affluent LGBTQI+ individual making claims about their reality and then compare this reality, to that of a working-class, minimum-wage person. To take it even further, it is often the case that the affluent person becomes an ambassador for “the community’s” rights, but in reality, their lived experience has almost nothing in common with that of the working-class individual. The working-class person is left with the illusion that their rights are being represented, while in practice no only they remain marginalised but can be exploited too. At the same time, queer thinkers and artists are fighting for the conceptual validity of their theories and works, which often (to me) feels disconnected from the world outside academia.

To conclude, I suppose the task of the writer (a term I prefer to use instead of “poet” for myself) is to imagine the unimaginable, to give voice to the unsymbolised, and to challenge dominant discourses by subverting and proposing new ones through the very medium of language. As for the revolutionary potential, I do not know. What I can say for sure, more representation from the basis is needed.

Could poetry be used to imagine what could be radically different realities? Could it contribute to a re-imagining of a different future through the power of words?

Poetry can certainly serve as a vehicle for imagining whatever we wish to imagine. But does it have transformative power to change the world if we assume that imagination in poetry serves a purpose for the betterment of society? Or at least the power to open up horizons to new meanings and potentialities? To me, this is ultimately a political matter, and unfortunately, I see very few signs pointing in that direction. This is relevant in the publishing sector, where literature and poetry have, to a large extent, become commodified subject to PR and marketing strategies and funding channels/awards that are not always transparent and are often aligned with governmental agendas. If a piece of work poses any kind of threat or has the potential to destabilise the status quo, it is unlikely to be published, at least within the Greek publishing reality. And even if it does get published, it will most likely come from small independent presses, which means it will not reach a wide enough audience to create the possibility of revolutionary change.

I suppose what I am trying to say is that your point may have been valid in the past, but I feel the rules of the game have changed. Consequently, the way we create art and literature must also change, though I am unsure in which direction. For example, I find it difficult to appreciate literature or poetry that merely celebrates the beauty of nature as relevant (even if I can admire its aesthetic qualities) at times when large-scale climate change deniers still hold governmental power across continents. Thus, the matter becomes not only what we write but also what we systematically and systemically avoid to write. To me, this kind of poetry is not only irrelevant but also misleading potentially dangerous and complicit by diverting attention. Furthermore, imagine this: if, in ten years’ time, AI begins to write poetry that surpasses human intellect, then the revolutionary potential of literature would no longer belong to us as a species, but rather to AI if it were ever to reach a threshold of consciousness comparable to our own.

I believe I touch on this matter in one or two of my poems. I am not certain if I have fully answered your question. Incidentally, I explore these very themes in my upcoming poetry collection, a work in progress that I am writing in English. Ultimately, yes, I do believe literature can be a form of resistance. In sum, my answer is: yes, we can imagine alternative realities. But can poetry really improve the human condition? The current state of affairs suggests otherwise.

What role does language play in your writings?

This is the most difficult question so far, and one I struggle to answer. It makes me reflect on what it is that I am actually doing. I don’t believe I follow any fixed set of rules when it comes to language use. A poem usually comes to me either in images and/or in words (mostly in Greek, but lately in English as well), and I tend to write in an associative, free-floating manner, trying to censor myself as little as possible. Both the theme of the poem and the use of language carry equal weight. At times, I even find myself inventing new words that may arise naturally in the process. When I return to a finished poem, it must feel aesthetically satisfying according to my own standards, while also carrying a sense of flow, a kind of narrative. When I read my poetry, I often see pictures the words have been transformed into something else. I do not follow any specific rules/form when I write. I just need to like the words. I have not studied creative writing, nor do I consciously follow established rules when it comes to the use of language (for better or worse). I see language as the tool to “do the job.” So, I am not sure if my response is technical enough, but it is the most honest one I can give you at this point in time.

Would you say that poetry and psychology are communicating vessels? If so, which is their binding thread?

I particularly like this question though please don’t take that to mean I haven’t enjoyed all of your questions so far. This one, however, carries a special weight for me because it touches on the duality of my roles: my profession as a psychologist, from which I make my living, and my role as a writer, from which I earn absolutely nothing (on the contrary, I am spending), and which I pursue purely as a passion. Sigmund Freud once said, “Everywhere I go I find a poet has been there before me.” I feel that both psychology and poetry, and art more broadly, are communicating vessels. Their meeting point is the human being: life and the human condition, its suffering, joy, complications, and the world we inhabit and act within. Art and its expression are sources of sublimation. Modern psychology seeks, broadly speaking, the alleviation of human suffering through applied research, experimentation, and scientific principles that lead to interventions. Poetry, on the other hand, is free to approach the human situation by whatever means it chooses let’s say it is subjectivity-sensitive. That freedom is something I deeply value; it feels profoundly existential to me, a return to basics without the need for elaboration or explanation. From an existential perspective, I believe both poetry and psychology are different roads leading toward the same “royal route towards catharsis.” They simply follow different paths, and their expressive means are different.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE