The Revolution of 3 September 1843 marked the end of absolute monarchy in Greece. The successful uprising, led by the Greek Army with the support of a large part of the Greek people, resulted in the granting of a constitution and the adoption of universal suffrage. Among the main leaders of the revolt was cavalry colonel Dimitrios Kallergis.

Background – The first years of the Modern Greek State

The Greek War of Independence was declared in 1821, following almost four centuries of Ottoman occupation; thanks to the struggles of the people, and with the support of the Great Powers, Greece was officially recognised as an independent, sovereign state with the signing of the London Protocol on 3 February 1830 (O.S.). Its first head of the state was Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias but, in the aftermath of his assassination in 1831, the Great Powers designated the young Prince Otto of Wittelsbach, son of King Ludwig I of Bavaria, as King of Greece.

Because Otto was still considered a minor, a regency council, appointed by Otto’s father, ruled in his place. The regents would soon become very unpopular, due to their authoritarianism and distrust of the Greek political parties. Otto arrived in February 1833, but it wasn’t until June 1835 that he reached the age of majority, ending the regency and assuming the throne as absolute monarch.

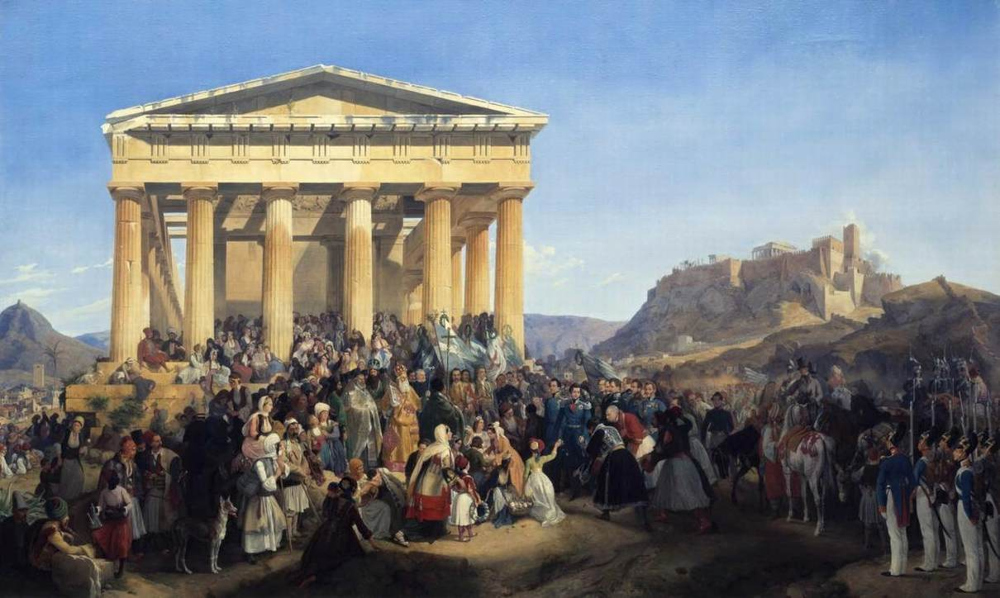

The Entry of King Otto of Greece in Athens (by Peter Von Hess, 1839, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Entry of King Otto of Greece in Athens (by Peter Von Hess, 1839, via Wikimedia Commons)

Bavarian authoritarianism and what was generally perceived as disregard for the locals perpetuated popular discontent, which was further fueled by the country’s dire economic situation, as Greece was facing a staggering debt and the king made massive budget cuts and raised taxes. In 1843, Greece would eventually declare bankruptcy.

The king had repeatedly rejected the popular demand for a constitution, until a conspiracy began to develop in 1840. Yannis Makriyannis, a distinguished fighter in the Greek War of Independence, initiated several other veterans who felt abandoned by the government, along with a number of prominent politicians from the parties of the time – most notably, Andreas Metaxas, member (and later leader) of the Russian Party and Andreas Londos, leader of the English Party (while Makriyannis himself was a supporter of the French party). In 1843, they brought the officer Dimitrios Kallergis into the conspiracy, to secure military support.

Dimitrios Kallergis

Dimitrios Kallergis was born in Crete in 1803, and came from a historic family line of the area of Mylopotamos. Following his father’s death, while he was still a minor, he was sent to St. Petersburg to continue his studies, and then to Vienna where he studied medicine. He abandoned his studies to join the Greek struggle for independence and, in January 1822, he arrived on the island of Hydra, bringing with him military supplies.

Left: Portrait of Dimitrios Kallergis by unknown artist, National Historical Museum of Greece (via Wikimedia Commons); Right: Portrait of Yannis Makriyannis by unknown artist, National Historical Museum of Greece (via Wikimedia Commons)

Left: Portrait of Dimitrios Kallergis by unknown artist, National Historical Museum of Greece (via Wikimedia Commons); Right: Portrait of Yannis Makriyannis by unknown artist, National Historical Museum of Greece (via Wikimedia Commons)

He took part in a series of military operations, and played a leading role in the revolutionary front of Crete since 1825, but without success. In 1826 he participated in the failed attack of Colonel Fabvier against Thebes; in 1827, he was the leader of the Cretan forces in the Battle of Phaleron, where the Greeks sustained a disastrous defeat. He was captured by the Ottomans, but was released after his family paid a large ransom.

Kallergis was a strong supporter of Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias, Greece’s first head of state, and even served as his aide-de-camp, as he pursued military career as an officer. Following the Governor’s assassination in 1831, Kallergis placed his support in his brother Augustine Kapodistrias, actively participating in the civil conflicts of the period. During the Bavarian regency, he was briefly imprisoned as a supporter of the pro-Russian party.

By 1843, Kallergis had become a colonel of the cavalry; at that time, he was initiated into the constitutionalist conspiracy (possibly by the leader of the Russian party, Andreas Metaxas). He was put in charge of the movement’s military wing, and they arranged for him to be transferred from the town of Argos and become Commander of the Athens cavalry. The commanders of the Athens infantry and the Military Academy had also become part of the conspiracy. Metaxas, Makriyannis and Kallergis were designated as the movement’s leaders.

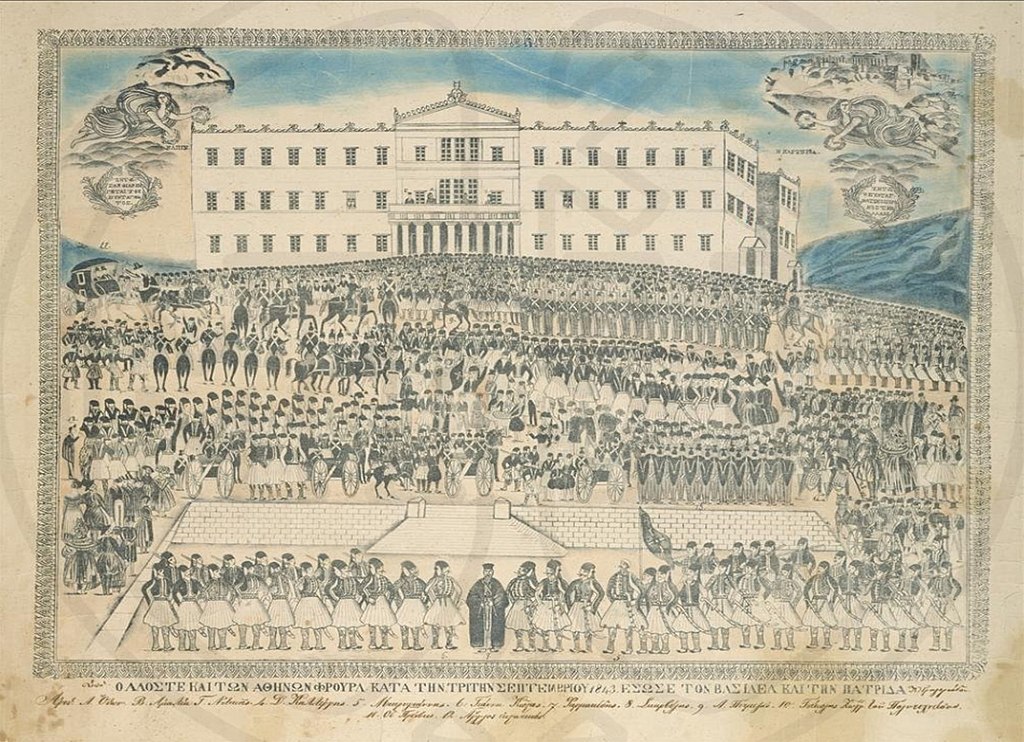

The 3 September 1843 Revolution, lithography by unknown folk artist, Benaki Museum (via Wikimedia Commons)

The 3 September 1843 Revolution, lithography by unknown folk artist, Benaki Museum (via Wikimedia Commons)

The 3 September Revolution

Although the group had initially agreed on the symbolic date of 25 March 1844, they had to rush the process as too many members had been introduced to the conspiracy and the leaders feared exposure. The gendarmerie indeed discovered the conspiracy and surrounded Makriyannis’s house on the evening of 2 September 1843 (O.S.). Kallergis put himself at the head of the Athens garrison and marched from Monastiraki towards the Royal Palace (nowadays the Hellenic Parliament House), with the men chanting “Hail to the Constitution”.

Kallergis sent a unit to lift the siege around Makriyannis’s house, and others to free political prisoners from the notorious “Medrese” prison, to occupy various public buildings –including the National Mint and the Bank of Greece– and arrest ministers. In the early hours of 3 September, he was joined in front of the Palace by a crowd led by Makriyannis. King Otto, still working in his office, was informed of the army’s mutiny, and sent his Minister of Defense to negotiate; after the latter was arrested by the mutineers, the king had to emerge from a window and address the mounted Kallergis.

Colonel Kallergis announced that the crowd would not withdraw until the king agreed to convene a National Assembly to draft a constitution. The king was also asked to dismiss the Cabinet and call a national election. Otto tried to stall, asking to meet with the ambassadors of the three Great Powers to discuss his options, but the insurgents did not allow foreign diplomats to enter the Palace.

After some consideration, Otto agreed to all the demands of the mutineers; he signed the decrees needed for the convocation of a National Assembly, and appointed a provisional government headed by Andreas Metaxas to prepare elections for a constitutional assembly. The bloodless revolution officially ended in the afternoon of 3 September, when the crowd was finally dispersed, after it became known all their demands had been accepted.

The 3 September 1843 Revolution, early 20th-century postcard (via Wikimedia Commons)

The 3 September 1843 Revolution, early 20th-century postcard (via Wikimedia Commons)

Aftermath

On 7 September 1843 (O.S.), Metaxas’s provisional government called for national elections; these would take place over several days in October and November 1843. All Greek males over 25 were allowed to vote. The election resulted in the “Third of September National Assembly of the Greeks in Athens“. The National Assembly promulgated the Greek Constitution of 1844 in February, which was adopted on 18 March 1844; it was then dissolved and elections were proclaimed for the first regular parliament. The first Constitution of Greece established the Constitutional Monarchy and was based on the French Constitution of 1830 and the Belgian Constitution of 1831.

By royal decree, the day of 3 September was designated as a national holiday, and Dimitrios Kallergis was awarded a medal and was named military commander of Athens. He was also elected to the constitutional assembly, as a representative of Cretans (although Crete was did not form part of the Greek state at the time). In remembrance of the revolution, the former “Palace Square” would be renamed “Syntagma (Constitution) Square”.

Otto would eventually be dethroned following a coup in 1862; in 1863, the Greek National Assembly elected Prince William of Denmark King of the Hellenes under the regnal name of George I.

In 1845, Kallergis resigned from the army and left Greece for London and later Paris. He served as minister in the 1854-1855 government under Alexandros Mavrokordatos, and then as ambassador to France. He is believed to have played a part in the negotiations that led to the ascension of King George. In 1867 he suffered a stroke in Paris and was brought back to Athens, where he died in April.

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Ioannis Kapodistrias, Modern Greece’s first head of state; 3 February 1830: Greece becomes a state; “Greece 2021” | The celebrations for the 200th anniversary of the country’s Independence War

N.M. (Intro image: The 3 September 1843 Revolution by unknown artist, Athens City Museum; Kallergis is portrayed at the centre on horseback, while Otto is shown at the Palace’s window wearing a red fez [via Wikimedia Commons])