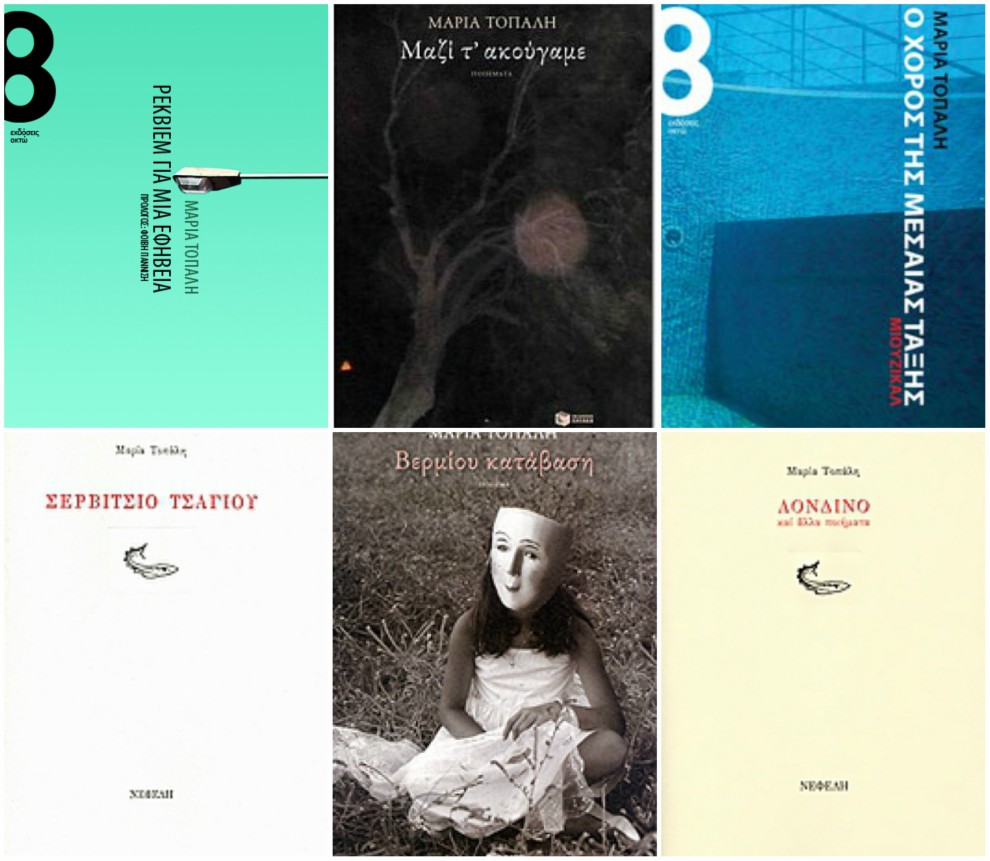

Poet Maria Topali was born in Thessaloniki in 1964. Her first volume of poetry, Tea Set, was published in 1999 and her second, London and other poems (short-listed for the poetry award of the literary magazine Diavazo), in 2006. Since then she has published the books Vermion Descent (2010, Patakis ed.), a theatre musical The Dance of the Middle Class (Okto, 2012) and also a book in collaboration with Konstantine Matsoukas entitled For four hands (Gavriilidis, 2013). Her poems have been translated into German, Italian and Slowenian.

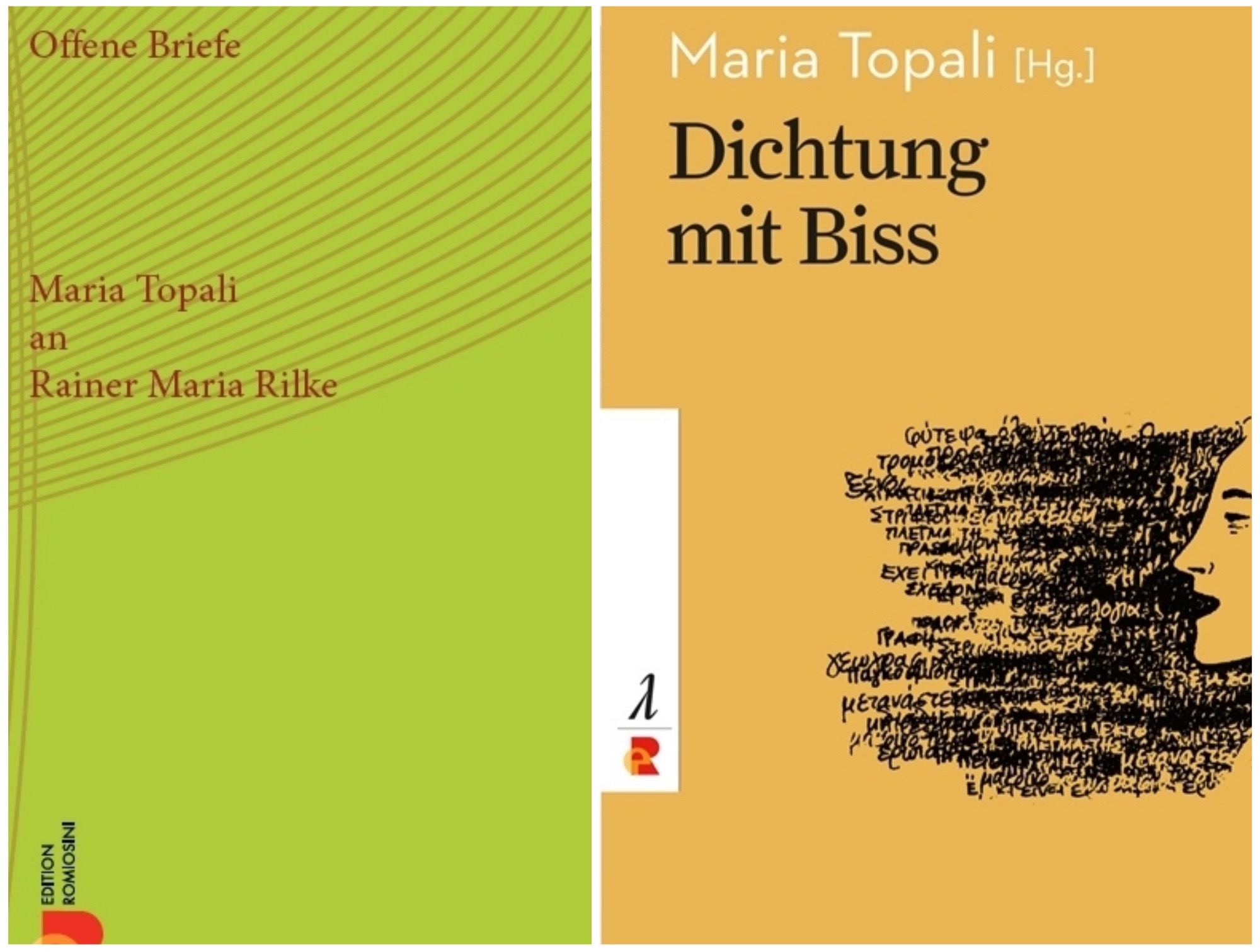

Since 1996 she has written poetry critiques and reviews for the journal Poiisi (Poetry) and its successor Poiitiki (Poetics), as well as for daily paper Kathimerini [Sunday edition, since 2006] and has translated prose and poetry from German, including selected poems by Brecht, Huchel, Lasker-Schüler and the Duineser Elegien by Rainer Maria Rilke (published by Patakis ed. 2011). Her most recent publications include: Offener Brief: Maria Topali an Rainer Maria Rilke (Edition Romiosini, 2018); Griechische Lyrik aus dem 21. Jahrhundert (Edition Romiosini, 2018); and We all sang along, poems, (Patakis Editions, December 2018).

Maria Topali spoke to Reading Greece* about what has changed and what has remained the same since her first poetry collection in 1999, noting that the binding thread between poems, translations, book reviews, narrations in prose and theatrical texts is poetry itself, “the magic and geometry of life”. She also talks about Dichtung mit Biss, an anthology of modern Greek poetry, which aims to “explore on the one hand the tendency for something new as compared former works, on the other hand the characteristics of this new poetry, since it is being created”.

She comments that “there is something special to be observed in the correspondence of modern Greek poetry with foreign elements”, that is the fact that “the new Greek poets, whether they are aware of it or not, are simultaneously global citizens/poets”, and that although “a particular local or even ‘national’ hue can add a certain charm to a work of poetry, it cannot, and especially in the long term, be the critical element of its resonance”. She concludes that “connecting poetry to real or imaginary roadblocks harbors a camouflaged form of orientalism” and that “any form of poetry, of literature, of art, has an obligation to go against the forefathers”, in order to offer new ways to imagine what can be radically different realities.

From Tea Set in 1999 to We all sang along in 2018, what has changed and what has remained the same in your writings?

A poet is, perhaps, not a very suitable outside observer of her own work. I can tell you what has changed and what has remained the same regarding my intentions and pursuits, but let others judge the results. When Tea Set was published, I was 35 years old; the book was not the product of a youthful surge of creation. I began writing in a rather careful and restrained manner, like someone trying out their voice and their approach. Starting out like this has a certain advantage – women poets, especially, often make such “late appearances”- namely that, in a way, the road to enthusiasm is reversed for us.

Therefore, since I now feel more certain of my steps, I allow myself to become more exposed, and my words to be more direct. Judging by the many responses I have received, both written and oral, after the publication of We all sang along from many strong readers whose opinion I appreciate, this intention of mine that I described corresponds to a great degree to the reader’s experience. Of course, one can always see the same glass half-empty: as time passes, each day brings us closer to the end of our life (and creation), and our fears and apprehensions start to shrink. Thus, as we grow up, we function under the power of “what is there to lose”?

Poems, translations, book reviews, narrations in prose, theatrical texts. What is the binding thread?

The binding thread is always poetry itself. It is poetry that I seek in the literary reviews, the musicals, even in readings and discussions of children’s and young adult literature, which I especially love and aim never to abandon. As my beloved poet Loukas Kousoulas says, poetry is the only metaphysics I accept: it is the magic and geometry of life. And the love.

In recent years the interest of foreign readers in Greek poetry has been rekindled, with an increasing number of poetry anthologies published abroad. Tell us a few things about Dichtung mit Biss. Griechische Lyrik aus dem 21. Jahrhundert and the three dimensions of the Greek poetry of the 21st century: political, global and innovative.

Dichtung mit Biss was “commissioned” by CeMoG (Centrum Modernes Griechenland) at Freie Universität Berlin. It is an anthology of modern Greek poetry, meaning the poetry that has been written, published and presented publicly in roughly the last twenty years. The anthology includes more than 50 poets and more than 150 poems in an excellent translation from the Greek by Torsten Israel. In it, I attempted to explore on the one hand the tendency for something new as compared former works, on the other hand the characteristics of this new poetry, since it is being created: it is too early for us to talk about more concrete features when this phenomenon is still evolving.

It is a motive for us to ponder on contemporary, dynamic developments. It is not an anthology comprised of the best, nor necessarily of those who “will remain”. Naturally, since the anthology is addressed to a German audience, I also tried to map out the country in its current phase, calculating in advance the curiosity of the potential reader: Which Greece and which Greeks make their appearance in the verses of modern Greek poetry?

What makes a national poetry appealing to a foreign audience? And, in turn, to what extent do Greek poets incorporate foreign influences in their work?

I will begin with the second question: there is no such thing as important poetry, at least in Greece (and probably anywhere, I think) without intense, deep correspondence with foreign elements. Why this happens is a complicated matter, but a factum non the less. If there is something special to be observed in the correspondence of modern Greek poetry with foreign elements, it is a higher degree of “naturalness”: the new Greek poets, whether they are aware of it or not, are simultaneously global citizens/poets. They swim in international waters even when writing about the family village in the mountains of northern Greece, if not especially then. This, too, has its interest.

Regarding the first question: “national poetry”. Hm. What is “national poetry”, really? Do you think that, in our day and age, it is wanted and necessary? There is certainly a kind of exoticism that is popular and always will be, especially when it comes to older poetry. But the objective is always good poetry, whether it be German, Greek, Egyptian or Argentinian. A particular local or even “national” hue can add a certain charm to a work of poetry, but it cannot, and especially in the long term, be the critical element of its resonance.

Vassilis Lambropoulos notes that “of all the arts, poetry has been identified as the most representative of the current national crisis. It constitutes the major cultural domain where the Greek emergency and/or exception are being negotiated”. What is the relationship of poetry to the world it inhabits? What can it mean for poetry to be political, or apolitical, in times of social and economic crisis?

Poetry that resounded current events in an obvious manner would definitely be of moderate quality. I believe that connecting poetry to real or imaginary roadblocks harbors a camouflaged form of orientalism – the natives rise up, the revolutionaries write and recite poetry, the timeless philhellenes are touched and lean with interest toward the southernmost edge of the Balkan peninsula: I prefer to leave behind me both the philhellenes and the national poetry we mentioned above. Both are, in essence, neo-colonialist, whether their intention be progressive or conservative.

Therefore, I can only interpret the turn of Lampropoulos’ phrase as follows, in order to validate it: “Poetry, definitely cinema, but also a part of music and theatre, had assessed in advance, to a great degree, the outbreak of the crisis sometime before it became visible to the naked eye”. Poetry (and any art) that takes itself seriously sends probes into the individual and collective soul. Before the outbreak of the crisis, Greek society was a massive bubble. Is it really a coincidence that in the years of this big bubble poetry was looked down upon more than ever? Some of the elders strained against the currents to keep the flame burning, some younger ones entered the dance dynamically and confrontationally – all of this took place within the first decade of the new millennium, when nothing foretold what was to come.

Any good, true poetry is political. Any explicitly political, opportunally political poetry is in danger of being passable or even poor.

To what extent can poetry be used to debunk stereotypes related to our ancestry, our national identity and our glorious but long gone past? Could literature offer new ways to imagine what can be radically different realities?

This is a very important question. Any form of poetry, of literature, of art, has an obligation to go against the forefathers: tradition, at least in the later period, is a peculiar continuum of rifts and connections. Therefore, literature and art necessarily do this, and you are very right to ask if and to what degree we can use them in order to achieve this.

So, I will propose an example. Imagine that, starting tomorrow, we stopped reading Solomos and Seferis (the two peaks of the 19th and 20th centuries) as purely national poets. Imagine that we started reading their works in a different way: as revolutionaries in their time. As bringers of newfound, radical ideas and ways. Imagine what it would be like, if, during this reading, we put “sexuality” next to “nationality”. We, however, have placed them in the Museum, deactivated. That truly is a greek peculiarity.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

*INTRO IMAGE: ©Themis Zapheiropoulos

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE