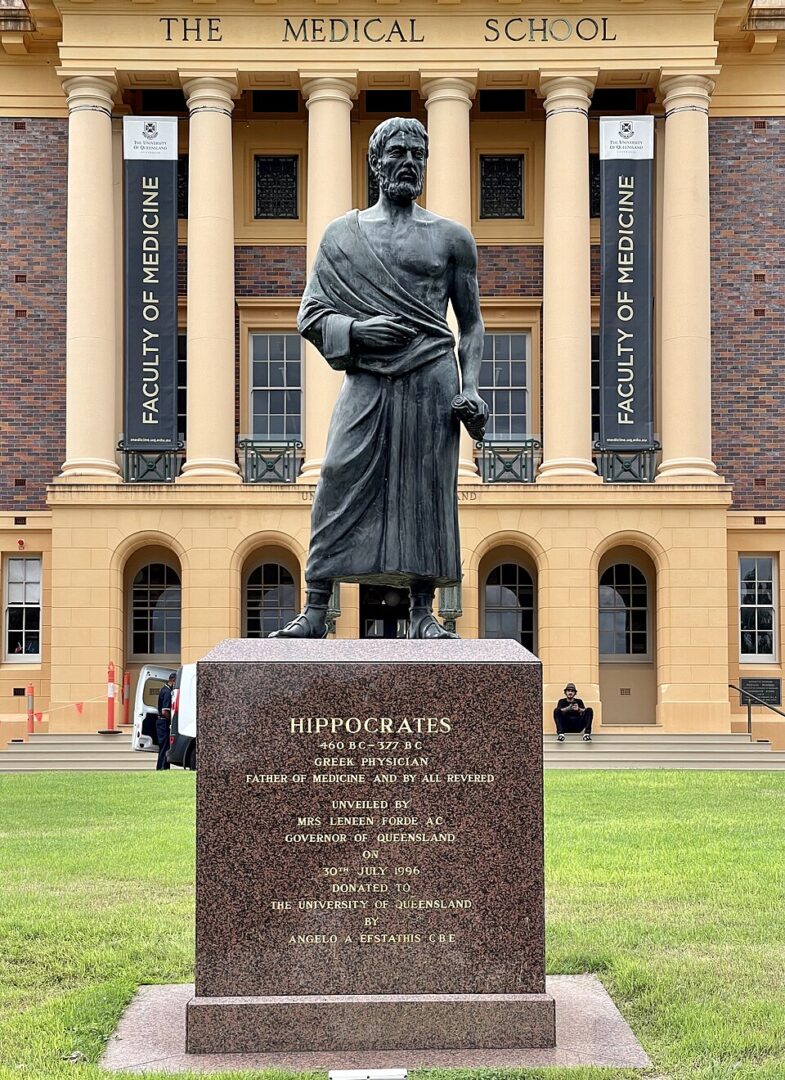

Hippocrates (c. 460 – c. 370 BC) was a physician in Classical Greece, born on the island of Kos. For his foundational contributions to the nascent field of medical science he has been dubbed “the Father of Medicine”.

Life and work

Not much biographical information is known about Hippocrates, as the main sources are not entirely reliable and some contain different accounts on his life. It is however generally accepted that he was born in 460 BC on the Greek island of Kos (now part of the Dodecanese island chain in the southeastern Aegean Sea).

Hippocrates is mentioned in famous works of his contemporaries, namely in Plato’s dialogues Protagoras and Phaedrus, and in Aristotle’s works Parts of Animals and Rhetoric; the latter refers to him as “the Great Hippocrates”, showing great respect and highlighting his value as an early systematic thinker in the study of nature and medicine, even though he disagreed with some of his theories.

According to his first and most comprehensive biography (written by the Greek physician Soranus of Ephesus, who lived at least 3 centuries later) he came from a line of physicians, who taught him medicine, while he may also have been a student of Democritus, and was probably trained at the asklepieion (healing temple) of Kos. He practiced medicine throughout his life and travelled to various parts of the Greek world. He is also said to have died at an advanced age.

Medicine as a rational science

Hippocrates’ most influential contribution to the field of medicine and science in general was that he proposed that diseases had natural causes, rooted in environmental factors, lifestyle, and diet—laying the groundwork for rational, scientific approaches to medicine.

He is believed to be the first person to attribute physical ailments to somatic rather than supernatural causes. Until that time, disease was widely regarded as a curse placed by gods; therefore, demonstrating the role that environmental factors and living habits had on health was revolutionary in and of itself, regardless of whether many of his specific theories would later be disproven.

One very telling example is the condition of epilepsy, which was regarded as either a malediction or even a sign of favor from the gods – hence it was characterized as “sacred”. In the treatise On the Sacred Disease, part of the Hippocratic Corpus, we find the first recorded observations of epilepsy, with the author attributing the phenomenon to an imbalance of bodily fluids, rejecting any metaphysical explanation.

Hippocrates also introduced the concept of prognosis and clinical observation, by emphasizing detailed, systematic observation of patients. He advocated for careful recording of symptoms, disease progression, and treatment outcomes – forming the basis of clinical case studies and patient history-taking in modern medicine. Additionally, he shifted some focus from just curing illness to predicting and managing it, helping physicians plan treatments and prepare for outcomes.

Hippocratic Corpus

The Hippocratic Corpus is a collection of around 60 medical texts attributed to Hippocrates and his followers. These works cover a wide range of medical topics, including anatomy, surgery, and ethics, and they served as essential references for centuries. The majority of these texts date from the Classical period, while there are also some works from the Hellenistic and Early Roman periods. This collection of inestimable value represents the central nucleus of ancient Greek medical literature, containing textbooks, lectures, research, notes and even philosophical essays on medical issues.

The medical framework underlying the Hippocratic Corpus was the theory of the four humors, a physiological theory suggesting that health is maintained by a balance of four bodily fluids: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. This, now debunked, theory dominated Western medicine for over a millennium and influenced diagnosis and treatment practices.

Arguably the most famous text of the Corpus is the Hippocratic Oath, an oath of ethics historically taken by physicians. Although not written by Hippocrates himself in its final form, the oath is attributed to his school and forms the basis for modern medical ethics—emphasizing the principles of medical confidentiality, non-maleficence, and professionalism. The use of an oath to be sworn by medical professionals, a practice still prevalent today, has its roots in this original text.

Legacy

The deep influence of Hippocratic ideals on his contemporaries is undeniable. His methods and those of the school named after him were studied and applied by subsequent physicians, as they were revolutionary for their time. This influence transcended the field of medicine: Aristotle’s approach to biology and empirical observation was clearly influenced by the medical tradition Hippocrates helped shape.

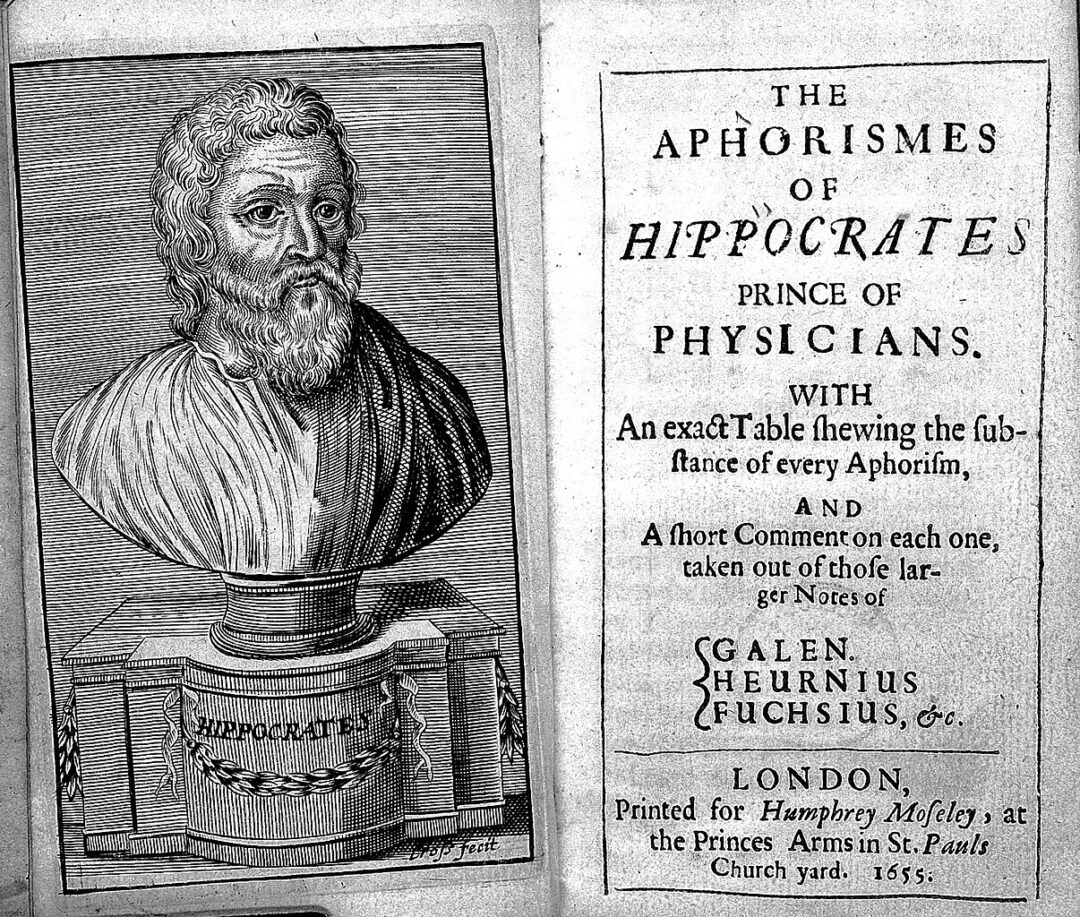

The empirical, observational methods described in the texts of the Hippocratic Corpus continued to be adopted by physicians for many centuries after the Classical Period. Galen of Pergamon [129–c. 216 AD], the most important Greek physician after Hippocrates, revered Hippocrates and integrated much of the Corpus into his own vast medical system, preserving and popularizing Hippocratic texts.

The Corpus was translated into Latin, Syriac, and Arabic; in the Middle Ages, the Hippocratic texts, together with the works of the aforementioned Galen, formed the basis of the curriculum for medical training in both Europe and the Arab world (Islamic Golden Age). The influence of the Hippocratic Corpus continued well into the Renaissance, until it was eclipsed by the advances in anatomy, microbiology and pharmacology in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Last but not least: Hippocrates and the Hippocratic Corpus have also left behind a rich vocabulary that has formed part of the medical lexicon for thousands of years. A number of words still used to this day, such as urethra, pneumonia or arthritis, first appeared in the writings of Hippocrates (while several more can be found in the works of Galen).

These contributions are in fact not limited to the scope of medicine, and include some words used in everyday conversations. For example, paranoia is also a Hippocratic term. A few more words have their roots in the four temperament theory, part of the aforementioned humoral theory: “Melancholy”, which literally means “black bile”; “phlegm” in the sense of a calm and cool response to stress or danger; “choleric”, meaning irritable; and “sanguine” (the only word with Latin roots) meaning optimistic. Other words deriving from humorism include, of course, “humor”, as well as “idiosyncrasy”; the latter is a compound word coming from idios “one’s own” + syn “with” + krasis, literally “mixture”, here used with the sense of “blend of the four humors”.

Finally, there are some clinical symptoms named after Hippocrates, due to having been first recorded in the Hippocratic Corpus, such as the Hippocratic facies (the change in one’s face interpreted as a sign of impending death), the Hippocratic fingers (nail clubbing) and the Hippocratic succession (gastric splash). “Hippocratic wreath” is also used to describe androgenetic alopecia.

N.M. (Intro image: Hippocrates refusing the gifts of Artaxerxes, 1792, Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson)

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Greek words about health and medicine in English; Medical advancements in Ancient Greece and the Byzantine Empire; The Plague of Athens as told by Thucydides: a timeless analysis of an epidemic

TAGS: ANCIENT GREECE | HISTORY | MEDICINE