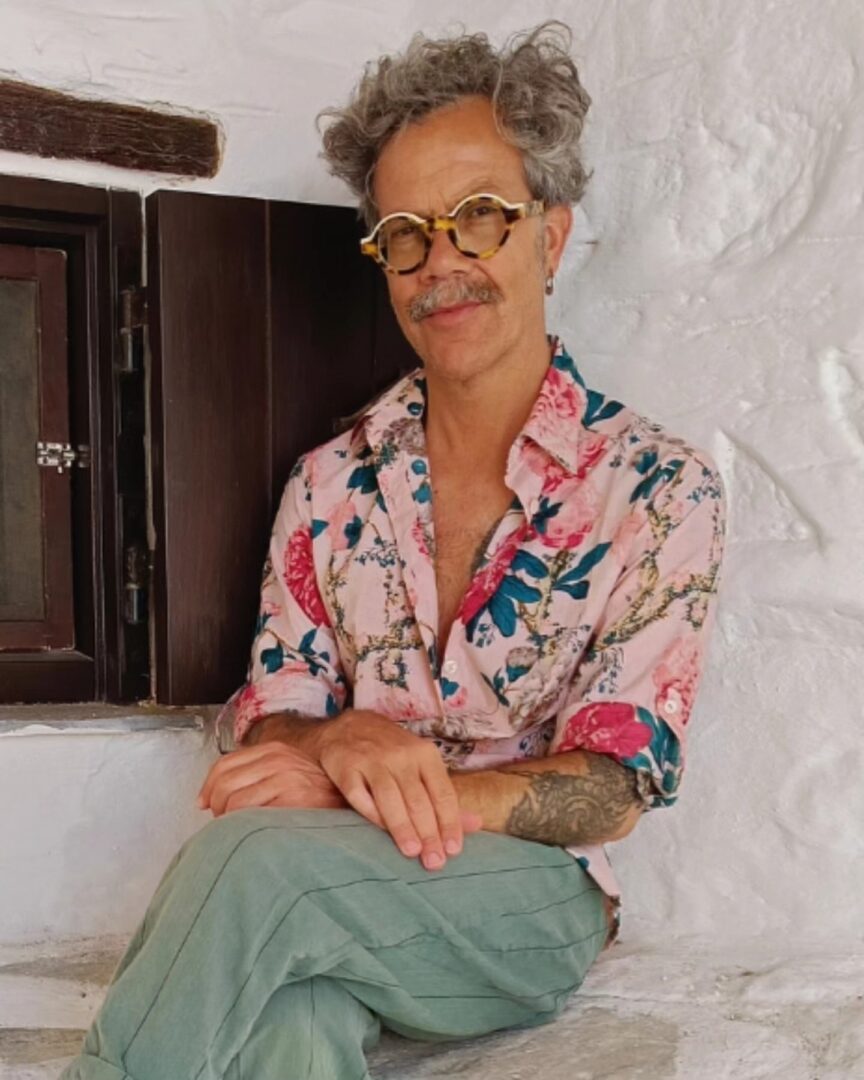

Panayiotis Kalivitis is a Panteion University graduate. He studied theatre in Athens and pursued postgraduate studies in London (Royal Holloway, University of London – MA, Department of Drama and Theatre, Playwriting pathway), followed by advanced training in New York with the SITI Company (The Viewpoints System & Suzuki Actors’ Training). He directs theatrical productions and writes plays and poetry. In 2020, he received the State Literary Award for the play Οι βελόνες της νεραντζιάς [Bitter Orange Tree Needles] (Sokoli Editions). Ηe pursues psychoanalytic work (Lacanian orientation). His first poetry collection Ο Ιονέσκο παραφυλάει στην Πόρτα Ιανουάλις [Ionesco lurks at Porta Ianualis] is published by Thraka Editions. He lives and works in Athens.

Your latest writing venture O Ιονέσκο παραφυλάει στην Πόρτα Ιανουάλις was recently published by Thraka. Tell us a few things about the book.

Ionesco is the first poetry book I publish. Yet, this is not my first encounter with writing poetry — it is the first time I have ventured toward a concrete publishing endeavor. For a long time, I had strong reservations about taking that step. This collection marks a personal breakthrough. For many years, I lingered, so to speak, on a threshold. Poetry was a heavy notion for me, as if I couldn’t bear its weight.

This book offers impulses of entry. The threshold remains a primary condition, with multiple signifying specifications. It gazes over the entire book — already from the title. The threshold of the door symbolizes a kind of passage, the transition from one state to another. A point of uncertainty and anticipation, a point of attachment between a familiar ‘before’ and an uncanny ‘after.’

Organized as a unified dramaturgy and structured in three parts, this book is an act; an attempt to bring forth the dialectic of transitions. You see, the threshold, although inscribed in the topology of transitions, may also become a site of dwelling, a space of inhabitation.

The collection is an act of declaration – not toward the aesthetic of the beautiful, but toward an aesthetic of the Real, of the Heideggerian Das Ding.

In your poems, you use concepts from the literary, philosophical and psychoanalytical traditions and use them as symbols, creating multiple levels of meanings. How are all these motifs transformed into poetic material?

In fact, I think they were transformed because I never tried to do so, to transform them into poetry, that is. There was never a conscientious attempt on my part to use materials from these three fields. Rather, I would say, they emerged organically through my associative process. Therefore, I would not say I used them but rather that I was used by them, and it is probably through this reversal that this transformation, this transmutation I would say, is dynamized into a stake of poetic articulation.

The intertwining of disparate elements, which resonate in a latent way, creates a network of polysemy and ambiguity, activating the reader’s inner reality. By shaping the right conditions for their identifications, ideas, and fantasies to emerge, it enables them to transform the aesthetic stimuli of the poem into personal narratives through their subjective imaginary. In this way, a hospitable space is created for the Other, for the Other’s creativity, allowing the Other to read something of themselves. Up to a point, rewriting the poem, projecting their own fantasies, their own world view.

Mapping the depths of our own imaginary, of our own jouissance, we touch something of the Real. That’s why there are instances when coming into contact with part of our trauma (the subject itself) can cause discomfort, feelings of revulsion, possibly even censure. It is then that the reading has touched something core, something of the reader’s Being. Something seemingly uncanny. Imbued with such structures of ‘meaning-making’, poetry does not demonstrate. It reveals. Something deeply personal. Something, therefore, painfully intimate. Simply put, one reads what one can see. And what one sees are the reflections of the self. Its most intimate identity. By touching something of the Real, poetry is not interpreted by instead interprets the reader.

As Aristea Tsantzou writes in her review of the book, “we follow the psychic and linguistic journey of the ego through three successive states: the imaginary security (Ab ovo), the symbolic transition (Janualis) and the traumatic desire of pleasure (Encore)”. Which are the main themes your poems delve into in this existential journey?

Indeed, Aristea Tsantzou’s reading was remarkably perceptive in that it emphasized on the collection’s structural relief, identifying many of its constitutive principles, its themes, its dramaturgical breathing, and rythms.

Every person must contend, in this life, with the non-existence of the sexual relation and with death. These are the fundamental determinants of the discomfort of Βeing. Each person chooses a singular way to respond to the fact that there is a hole, the hole of the non-existence of the sexual relation. All the impasses of the modern subject are inscribed there: the question of sexuation and the paths of gendering, the class relation, the political, and the very fact of existence marked by discontent.

Ι reckon that writing poetry partakes of the dialectic of desire. It is inscribed within a presupposition: to attune oneself to the unknown, guided by the unbearable — the inhuman within the human. In other words, to fall into politically correct moralism — where prejudice, confused and unspoken affects, and self-serving skepticism are interwoven — bars access to the unconscious of the divided subject, which, in my opinion, constitutes one of the primary sources of the poetic. Wild, raw, primary — and thus universal. Collective.

Paraphrasing Merleau-Ponty, poetry gives us access to that which cannot be said — to the unrepresentable, the impossible, that which eludes us; in other words, as aforementioned, to the Real, to the Heideggerian Das Ding.

Would you say that poetry and theatre constitute communicating vessels? Which is their binding thread?

From their very beginnings, theatre and poetry were bound by strong, unbreakable ties. Like Siamese. Ancient Greek theatre is referred to as dramatic poetry. Ancient Greek dramatists were also called poets. Throughout their course and in a relationship of constant (but unattainable) separation, both arts defended their distinctiveness through the naturalness of their attraction. There are countless examples where, to the extent they attempted to be autonomous, they were multifacetedly inspired by each other. Theatricality in poetry and poetry in theatre both constitute uplifting.

Personally speaking, the connection threads are multi-textured. I can safely say that theatre is a living cell of me. Therefore, irrevocably influenced by what performances I have seen, what plays I have read, writing poetry is like doing the performances that escaped me. This escape is an indicator of managing the impossible as a poetic possibility. A poetics with theatrical narrative structures inscribed in a personal aesthetic code.

Physicality is used not as a field of naturalistic representation, but as a field of symbolic articulation. The body, understood as a phenomenological field, freed from its realistic specifications, is integrated into an ever-redefining network of semiotics. Through practices of narrative de-subjectification -rooted in the ancient tragedy chorus- as proposed by Artaud and Grotowski and more contemporary practitioners such as Romeo Castellucci, a corporeality emerges that is articulated in space and time with musicality and internal geometries. This corporeality is influenced by the ground-breaking imagery brought to art by Caravaggio, as well as by more contemporary artists, such as Francis Bacon and Pier Paolo Pasolini.

Close-ups, uncanny enlargements focusing on the unforeseen and the unexpected, visual angles that indict the gaze (fostering subjective division), theatrical contrasts and depictions through theatrical conventions, driven by rawness, constantly dismantle the ideal and abusive idealization, inviting us back to the ritual of libations (choikotita). To blood, to sweat, to all the fluids of the flesh, to what unfolds within a circularity articulated in pleasure and pain, in jouissance.

The afflicted body is centered in its inability to redeem and be redeemed. Opening up a dwelling space between despair and compromise. With at least one spectator/reader it validates the defining theatrical convention through the act of reading, we might say, to paraphrase Peter Brook slightly. An ongoing flirtation, with the performative agony of the theatrical act.

What about language? What role does language play in your writings?

As you know, the book is prefaced by a couplet from Rene Char: “the words that will emerge know things about us that we ourselves ignore”. These defining verses state something fundamental about the relationship between language and modes of writing. It is not the writer who holds primacy, but instead language and its function. The words that will emerge. The way they will emerge. Heidegger drawing on a verse from Hölderlin tells us: “… poetically man dwells…”. For Heidegger, human dwelling is an attunement to the address of language (the supreme address) only insofar one respects the very essence of language, its scope and function. Language is not a tool mastered by man; rather, it is the sovereign mistress of man. Indeed, it is language that speaks. If man truly listens to the call of language, it is the speech that talks (the talking speech, as we may say) that unfolds within the poetic element.

The more poetic a poet’s work is, the freer becomes their speech, that is, the more open and ready to accept the unpredictable. Language manifests itself as absolute singularity, the singularity of the poet’s utterance. Language as code. A poetry that uses the code by serving it. But also subverting it. Upsetting it, disturbing it, traumatizing it, enlightening it, violating it, making it bleed, and drinking it. Yet it doesn’t define it. It doesn’t control it. There is something that escapes. The poet becomes the offspring of language, but also an orphan of the language. The conditions are met to penetrate the uncontrollable, as Derrida suggests: “reading must always aim at a certain, invisible to the author, relation between what he controls and what he does not control within the very structures of language he employs”.

Poetry undermines and violates language as a conceptual structure, as a communicative system. It ought to bear witness to the rotten common sense and dominant discourse. In this context, poetic utterance evacuates meaning, creates ruptures within meaning, a process of déchetisation—an un-authorization of meaning. It aims at the contraction of meaning, at revealing an au-delà—a beyond of meaning. It aims not at interpretation through meaning making, but at the unrepresentable, that is, at the Real at its core. Therefore, it is not concerned with the automatism of the signifying chain, but with the accidental, the unexpected, the traumatic encounter with an element unassimilated by meaning – a scar of language carved on the body, as Lacan tells us.

So, a poetry emerges that does not pronounce, does not explain. It delves. It opens chasms. It leaves its traces where language stops.

How do contemporary Greek writers converse with global literary trends? Where does the local/ national meet the global and the universal?

In contemporary hyper-digital social structures, the boundaries between the local/national and the global have contracted. However, they have not yet been eliminated. I reckon that contemporary Greek poetic production is to a satisfactory degree connected to global trends. There is an awareness of what is currently being written globally, supported by with very effective translation reflexes.

The globalization and internationalization of the communal fabric, staffed and constituted by digital citizens, ensures common ground in terms of their themes, concerns and preoccupations, but also experimentation of form in a constant search for the most appropriate poetic articulation. After all, let us not forget Heidegger’s reminder that space and time are not always measured by the prevailing standards of contemporaneity. Poetically, then, humans dwell in the panorama of a common realm, where dwelling is founded upon the poetic.

As in other fields, support and concern for the promotion of domestic poetic material is inadequate. For this very reason, what you are doing under the auspices of the Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs is not merely necessary and important. It is valuable.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE