Katerina Gkiouleka was born in Athens. She is a graduate of the German School of Athens and studied at the Technical University of Munich. She currently practices architecture in Greece. Projects and studies in which she held positions of responsibility have received notable distinctions. For many years, she has been the author and visual editor of the blog Mechanical Pencil – (awkward) stories and verses online, where she exclusively publishes her own short prose and poetry. Her poems have also appeared in various online literary magazines and blogs, initially under the pen name Poupermina (Mechanical Pencil).

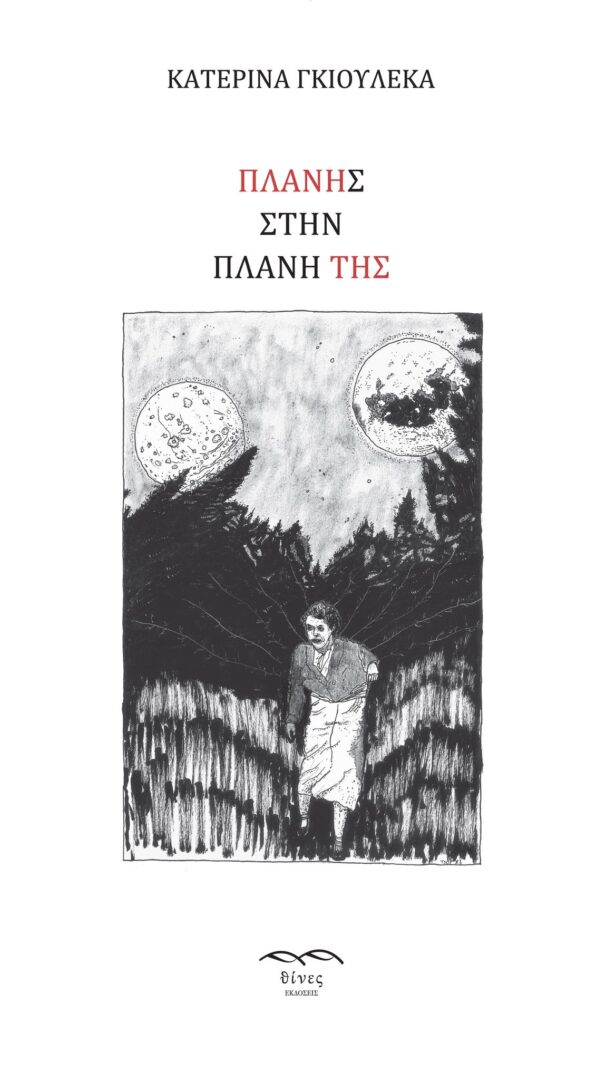

In April 2024, her poetry collection ΠΛΑΝΗΣ ΣΤΗΝ ΠΛΑΝΗ ΤΗΣ was published by Thines Editions, under the direction of Zizi Salimba. The book was edited by the literary scholar Dioni Dimitriadou and features original artworks by visual artist Giorgos Tsopanos. It comprises 74 poems written between 2017 and 2022. Selected unpublished poems from her work, alongside fifteen other female poetic voices, were included in the collective volume Sixteen Pens Weave the Contemporary Fabric of Poetry edited by poet Kostas Th. Rizakis, with a critical commentary by Isidora Malama, and visual works by Fotini Chamidieli (Koukkida, 2024). She has also contributed to thematic literary anthologies and is a member of the poetry circle Steriani Zali, hosted by Monoclebookstore.

Your first writing venture ΠΛΑΝΗΣ ΣΤΗΝ ΠΛΑΝΗ ΤΗΣ [Errant in (her) error] was published by Thines. Could you tell us a few things about the book and elaborate on its title?

Ι would like to thank you for offering me the opportunity to speak about my book. Of course, there is no better way to become acquainted with it than by reading the poems themselves. Still, I will attempt to offer you a glimpse. This is my first attempt at publishing. I differentiate it from any attempt at writing, because it was preceded by my personal blog, “Mechanical Pencil – (awkward) stories and verses online”, where a large body of my writings gathered over time. By the end of 2022, a certain cycle had been completed, and in a way, the writings felt cramped on the blog. They seemed to demand a passage forward – to urge my writing toward a new stage. Trusting my intuition, I chose to take that first step through poetry selecting poems written between 2017 and 2022. After making substantial cuts, I shaped a collection of 74 poems, divided into four sections, each guided by the rhythm of the daily cycle of time. The arrangement follows the moods that emerge from, and the imagery contained within, the individual verses.

In retrospect, it might sound like a dry, methodical process but in truth, the shaping of the collection was, to a remarkable extent, an entirely spontaneous act of creation. It was a seamless transition from the blog’s scattered labels to a unified poetic body. The four sections of the book took their names from the zones of the twenty-four-hour cycle, and each poem was given an epititle – one that reflects its position within that structure and anchors it to the whole.

The book’s length often surprises readers, particularly those unfamiliar with the background of the poems, which originated from the much more extensive blog. It also stands in contrast to readers accustomed to shorter, more thematically focused collections. Still, I feel compelled to stand by my decision not to present this earlier material in a segmented manner, especially since the structure of the collection is, by design, a reflection of a long and hazy journey through time. (1)

The poems are written in free verse, yet they carry an underlying sense of linguistic rhythm. Rhyme is employed only sparingly – mostly when there is a tenderly wry mood toward content.

As the collection gradually moved toward its final form, a deeper connection began to emerge between the wandering through the hours of the day and the planetary motion itself. It was at this point that the title ΠΛΑΝΗΣ ΣΤΗΝ ΠΛΑΝΗ ΤΗΣ [Errant in (her) error]revealed its fitting resonance. The alliteration of πλάνης (errant), πλάνη (error), and πλανήτης (planet), in Greek the phrases ‘ΠΛΑΝΗ ΤΗΣ’ and ‘ΠΛΑΝΗΤΗΣ’ (‘her error’ and ‘planet’) sound the same when written in capital letters]—offered a phonetic and semantic echo that captured the collection’s core. This word-centric or language-centric writing, as described by Lilia Tsouva during her presentation at the 2024 Thessaloniki Book Fair, is a thread that runs throughout the work.

Within the book, the oscillating journey through moods, questions, and lived experiences finds its counterpoint in the inevitability of repetitive planetary motion. This contrast subtly anchors the poetic self within the scale and position it truly occupies in the greater order of the world.

At this stage, a fruitful collaboration took place with my editor, Dioni Dimitriadou. Next, my publisher, Zizi Salimba – who embraced and supported with persistant personal work the project with genuine enthusiasm from the very beginning – invited illustrator Giorgos Tsopanos to read the collection and create original artwork for both the front and back covers. What emerged were two artworks that, to me, were entirely unexpected; yet they resonate beautifully with the fate of the poetic self, cast adrift in the world, a theme that feels anything but foreign within this collection. He also introduced subtle gothic elements, drawn from his own distinct artistic vocabulary.

Your poems often evoke a haunting, dreamlike atmosphere, full of symbolism, imbued with both nostalgia and a quiet defiance. Which are the main themes your poetry touches upon? Are there recurrent points of reference in your writings?

Your description does indeed fit the book – or at least, I would be glad if readers saw it that way. I had always thought of it as a work brimming with deeper emotion, judging by my own state of mind during the writing process – until the collection was later praised (generously, I must acknowledge) for its structural rigor. That response compelled me to interrogate it myself, to see whether it might finally confess that to me as well.

There was no deliberate foreshadowing in the shaping of the themes. These are subjects that preoccupy me, consciously or unconsciously, and they surface alongside families of words that take form in my thoughts or at the tip of my pencil (or, rather, during typing). The title of my blog, Mechanical Pencil, deals with that, the partly spontaneous writing. And of course, it also refers to the primary tool of my compositional work in architecture: the mechanical pencil – through which creativity, again, filters the demands and the mundane rational data, and the unified design, seems to emerge effortlessly the moment the pencil touches the paper, as if composing all on its own.

As for themes, I would name the recurring inquiry into (un)certainties – hence, also, delusion; the depiction of inner psychic or spatial landscapes through imagery; the futility of the human condition; language itself, as a partially inadequate instrument of perception, a means of naming and receiving reality, of shaping thought; the fact of repetition of personal patterns, or even obsessions; dialogue with the inner self; a first-person experience of space and time, whether separately or in synchrony; otherness, the absent other, the solitude of existence; and, always, art, that sole entity capable of penetrating us and stirring upheavals within, upheavals which, in turn, open new horizons and refine both our perceptive and expressive tools. Nor is the feminine perspective concealed. There are also poems that converse with dreams and bear, in their epititles, the German word Traum (dream) and the Greek word Trauma. Though unrelated etymologically, and linked only by sound, they nonetheless converge in shaping and giving voice to the psyche.

The nostalgia you perceived relates primarily to language’s inability to remember – to grasp and articulate something vaguely enchanting, something that seems to belong to a time before language even entered the subject’s life. The quiet scepticism has more to do with a kind of reconciliation – a coming to terms with fate, and with the fellow passengers of one’s journey through life.

You also experiment with language playing with words in their various meanings. What role does language play in your poems?

Though not intentionally, language claimed a central place in my poetry from the very beginning. In hindsight, I read this as a kind of provocation – or invitation – to communicate, a resounding appeal to the world. An articulation of speech where, until recently, something in me stuttered my own personal coordinates. A mating song (like that of birds or marine mammals) offered up into the poetic stage. I introduce myself as a poetic subject; I hope what I’m trying to say makes sense. And of course, I build with language – I construct – because that is what I was taught to do and what I practice professionally.

Language exerts a formidable enchantment over me. First and foremost, its rhythm,

its connotations, alliterations, homophonies; the improbable vocabularies of various fields and disciplines, its dialects, the slumbering words of bygone eras, the Greek of Cretan Renaissance poetry, its oblique deviations, its lapsi, its wordplay – the competing associations crowding within it, all jostling to be spoken. All those things that not only shape thought, but also know how to shift it creatively. Within these inexhaustible linguistic varieties, the potential of poetry already lies in wait: the materials of its unpredictable Avant-garde scenography hinted at.

To confirm a poem, I always read it many times by heart to hear its voice.

Thus, since language enchants me, it compels me. It… writes me. And as the inescapable medium of verse and poetry, it becomes the primary instrument of personal offering, the thread with which the poetic self is woven.

How is poetry related to the world it inhabits? Could it be used to help form different narratives about the world?

It is directly related. I would even say unmediated. The world that surrounds us shapes us; it enriches or deprives us, confines us or projects us to the world, teaches us or conceals from us. It identifies us, or demands our identification with pre-constructed models and at the same time may isolate us as unclassifiable. The poetic subjects, shaped by the circumstances of their time, speak in the language of poetry about the pain of the human condition

and the boundaries of the social bond. In their verses, they trace unforeseen correlations,

signal latent possibilities, describe their sidelong gaze at the world, convey moods – at times of tender reconciliation, at others of insurgent energy – sounding the alarm of urgency.

Perhaps this is the right moment to note that I am not drawn to poetry as a statement, but rather as a possibility, a version. This is why I find myself captivated by poets and voices that are vastly different from one another. I would not easily choose a single figure, movement, or generation.

Where does the architect meet the poet in your work? Would you say that architecture and poetry constitute communicating vessels?

In our time, the interdisciplinary formation of personality has been pinpointed. I write as a middle-class woman, a mother, an architect, and so forth. Of course, over the years, the daily immersion in a specific field profoundly influences the way we see, or determines the themes we choose to see, ignoring others. A doctor friend once described how, without intending to, she found herself observing, on the arms of passengers in a bus, whether good veins for blood draws were visible. An architect, looking out from the window of that very same bus, studies spatial relationships, architectural elements, light and shadow, shades, pathways. Personally, I perceive space and its experience, habitation or conquest, through the filter of a woman architect. It’s with these, and whatever other baggage and identities I carry, that I write. Yet, these identities do not appear clearly delineated, each confined solely to its particular occupation.

Beyond the obvious mirroring between, on one hand, the poetic essence in architecture – the lyricism in its lines and the compositional form-shaping outcome, along with its dialogue with the landscape or broader environment, concepts which, incidentally, remain relatively ignored to the wider Greek public – and, on the other hand, architecture’s influence on the composition of writing, architecture and poetry converge in their use of lived experience. They grasp spatial and temporal qualities; they perceive, comment on, and respond to decay, entropy, the chiaroscuro of life; to the challenges of places and landscapes; to grounding and suspension; to the subtlety of shades; to the capacity to introspect the private and provoke the collective; to the staging of temporarily permanent habitats, and to the hosting of their visitors.

In what ways do contemporary Greek writers converse with global literary trends? Where does the local/national meet the universal?

We are living, especially as experienced in the Western world, in an era of widespread globalization. All the themes that touch on existential anxiety, ontological questioning, the search for identity, gendered expression, the negotiation of otherness, the proposal of alternative paradigms, the human condition today, the environment and climate change, the reception of art, the role of AI, our stance toward current political challenges and global conflicts, are all areas in which the Greek creators can indeed converse and contribute on the international stage, provided they carry a grounded sense of place, robust expressive tools, and a distinct, original voice. Yet in this field, a language centric, especially when poetic, writing in Greek proves more difficult to communicate globally. Its resistance to translation becomes a challenge in itself.

We’ve drifted quite far from the book and the poems themselves. I’d like to close with a few verses and thank you and Reading Greece once again for the invitation to this interview!

Just then however she retired

gently closing the translucent screens

having as guides the perfect dovetails

and the mortices of the bearing cypress wood

with a well sharpened reed

she was cutting herself skilfully

and that, years aplenty

before the age of

the overseas trading

of alum

[Excerpt from the poem The Calligrapher]

>>>

Above all no more meanings

no more conclusions and theories

since forever all tenuously proven

nor to consider it, to explain the absurd

let’s say, how did absence ever learn

to unwind the watches or how on earth

did the beautiful smokestack Lato

having swam from Crete diagonally

upwards to the Meadow of the Gods

slip later the crafty one

the Philopappos’ way;

[Excerpt from the poem Suspicions]

(1) The poems that were included in the poetry collection Errant in (her) error, except those that had already been published on literary websites, were removed from the blog and have now found a new home in the printed book.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

INTRO PHOTO ©Vaggelis Tsiamis

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE